In 1996, the French postal service issued a series of commemorative stamps, “French Heroes of the Detective Novel.” For mystery readers accustomed to a canon of fictional detectives that begins with Edgar Allen Poe’s Auguste Dupin, gains popularity with Sherlock Holmes, and achieves its golden age in Hercule Poirot, it’s a curious collection of characters.

Few American and British readers of detective fiction will recognize the leadoff character, Rocambole — criminal schemer, remorseless murderer, hardened convict, and redoubtable avenger. The adventures of Rocambole, written by popular novelist Ponson du Terrail and published in daily newspaper installments, were all the rage in mid-nineteenth-century France, although none were ever translated into English. Today only antiquarians read the adventures of Rocambole, although older French television viewers fondly recall the daily broadcasts of his exploits in short serial episodes from the 1960s. Still, Rocambole has left a popular imprint on French memory in the adjective rocambolesque — “astonishing, outrageous, over-the-top, totally unbelievable” — invoked in everyday speech and journalism.

Thanks to the Netflix series Lupin, the “Gentleman Burglar” Arsène Lupin is back in circulation. However, the protagonist of that series, Assane Diop, is only loosely based on his namesake. In 1905, author Maurice Leblanc created the clever criminal and avenger Arsène Lupin, whose short stories were published in in the monthly magazine Je sais tout (“I know everything”), as a French rival to Sherlock Holmes. Today, the character’s continuing commercial success is due largely to Lupin III, a Japanese manga and video game character. Still, the adventures of Arsène Lupin remain a multigenerational source of reading entertainment within France, and Leblanc’s short stories continue to be assigned in intermediate French language classes.

Aficionados of locked room mysteries sometimes include Gaston Leroux’s The Mystery of the Yellow Room (1907) in the genesis of that subgenre. Like many of his Anglo-American confrères, the brainy newspaper reporter Joseph Rouletabille is an amateur detective. Through meticulous investigation and astonishing logic, Rouletabille solves the locked-room conundrum of the attempted murder of Mathilde Strangerson. Along the way, however, he discovers that his father is a notorious criminal mastermind. In the sequel novel, The Perfume of the Lady in Black (1909), Rouletabille broods over whether his father’s degenerate inheritance afflicts him as well, and despite tireless efforts the amateur sleuth fails to apprehend his paternal nemesis.

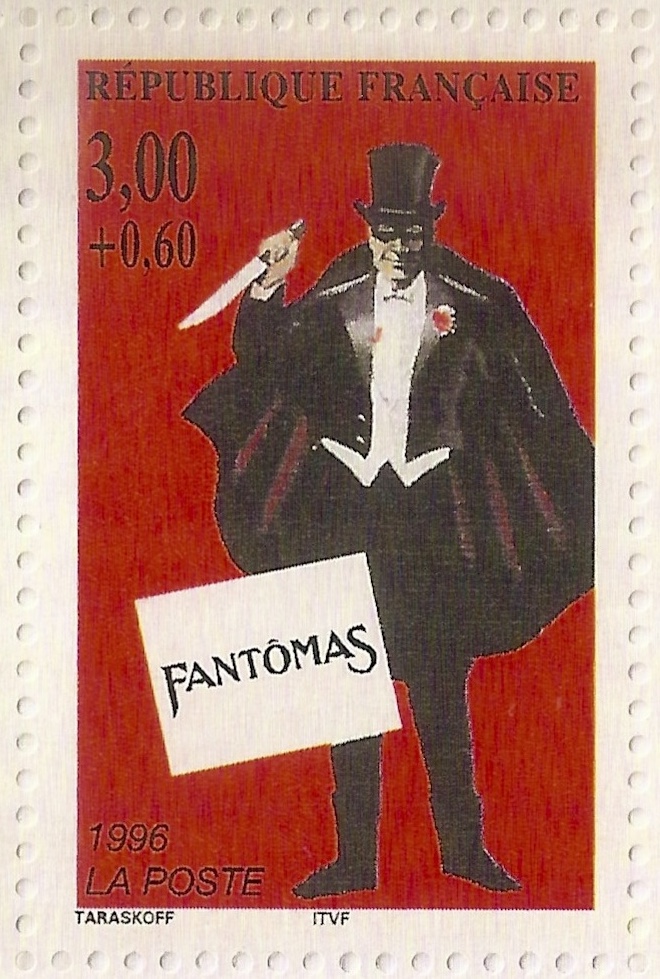

It is somewhat baffling that Fantômas —“Lord of Terror,” “Genius of Evil,” “Emperor of Crime” — is included among heroes of the detective novel. Fantômas is a master-of-disguise criminal with countless identities. The instigator of spectacular thefts, an imperious gang leader, and a mass murder, he repeatedly evades capture over the series of thirty-two Fantômas novels (1911-1913), co-authored by Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain and issued in as many months. A darling of the French avant-garde and surrealists in the early-twentieth century, the menacing shadow of Fantômas continues to inspire artists, filmmakers, and musicians in the twenty-first. Few enthusiasts, however, have read the original series of novels, among which fewer than one-third have been translated into English.

American and British mystery fans are sure to recognize Chief Inspector Maigret, the quintessential Sûreté detective and an enduring figure of French nostalgia. Among French detectives, Georges Simenon’s Maigret series most closely adheres to the Anglo-American genre, continuously published and reissued in English translations since the 1930s, as well as being adapted for radio and television by the BBC. However, Maigret is not a master of ratiocination who displays brilliant logic to solve crimes, nor does he follow standard police procedures of gathering evidence and applying forensic analysis. Rather, he is what the French call a policier nez, a detective who “follows his nose” once he has intuitively sniffed out his criminal culprit.

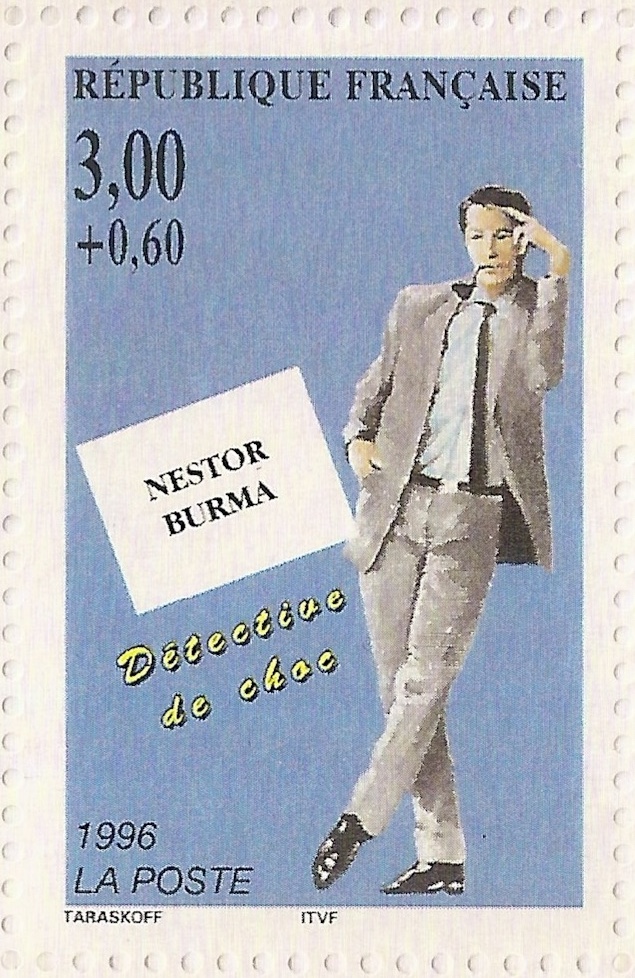

Surrealist Léo Malet began writing novels featuring “Shock Detective” Nestor Burma under the Nazi Occupation and continued on to achieve commercial success in the 1950s with the fifteen-volume “New Mysteries of Paris” series (1954-1959). Private investigator Nestor Burma of the Fiat Lux Agency is the anti-Maigret, a former anarchist and fiercely independent operator who is deeply suspicious of the police and only cooperates with them when required. While Malet is a foundational author for later French hardboiled néo-noir crime writers, English translations of his novels are spotty and few. Nestor Burma mysteries remain popular today in France and across continental Europe thanks to a long-running television series from the 1990s.

This blog provides opportunities for readers, particularly those limited to the English language, to explore the cultural history of French crime and detection stories over course of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Nearly all fans of the classical mysteries are familiar with a genealogy that starts with Edgar Allen Poe’s Auguste Dupin, leads to Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, and culminates in Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, which assures the triumph of the indefatigable detective over the criminal culprit through the careful collection of evidence and logical inference (ratiocination). In French popular novels about crime over this same period, by contrast, detectives, criminals, and avengers were more versions of one another as heroes and antiheroes, than opposed to one another as victor versus the vanquished.

In France from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, inherited tales and concrete historical conditions gave rise to popular stories about criminals and their wily ways. Over the next two centuries of political upheavals, economic transformations, social dislocations, and the rise of mass media popular fiction, crime stories became increasingly fantastic, popularly consumed not for their veracity to lived experience but as sensationalized entertainment. The serialization of French crime and detective stories over this period were fueled a commercial dynamic of publishers pursuing profits, authors seeking celebrity and wealth, and readers demanding even more spectacular stories that adhered to familiar conventions while introducing novelty.

This blog begins with deep dives into the original shady detective Eugène-François Vidocq and the elegant criminal Pierre-François Lacenaire, before moving on to such fictional characters such as Rocambole, Arsène Lupin, Rouletabille, Fantômas, Maigret, and Nestor Burma. A host of other popular and lesser-known fictional characters, as well as actual police detectives and criminologists, will be encountered along the way. These dubious detectives, clever criminals, and egotistical avengers were energetic, confident, duplicitous, and imperious supermen who rebelled against and rose above the uncertainties of their eras. Mediated by a mass print media of newspapers, magazines, and popular novels, readers reveled in the exploits of imaginary heroes who asserted their individual wills against overwhelming odds.

Updated: October 27, 2025

Illustrator Mark Taraskoff, “Héros français du roman policier.” Series “Personnages Célèbres,” La Poste, 1996. Author’s collection.

Robin Walz © 2024

Leave a reply to Marcus Ellis Cancel reply