Cover of Le Mystère de la Chambre Jaune by Gaston Leroux. Paris: Pierre Lafitte, 1908. Criminocorpus.org: Bibliothèque des littératures policières, Paris.

No one could explain it. Late at night, Mademoiselle Mathilde Stangerson had retired to the guest bedroom attached to her father’s pavilion laboratory, rather than return to the family chateau. At half-past midnight, the clamor of overturned furniture issued from the room. Mathilde’s voice cried out, “Murderer! Murderer! Help, Papa!” A gunshot sounded. Professor Stangerson rushed to the door, found it firmly locked, and called upon his groundskeeper to help break it down.

In the room, Mathilde lay stretched out on the floor next to the bed. Her throat was bruised and covered with fingernail scratches. Blood pooled from her forehead. Mercifully, she was still alive. The family physician soon arrived and accompanied her to the chateau to recover.

But where was Mathilde’s attacker? No one else was in the room, nor was anyone hiding under the bed or behind the furniture. The door had been bolted from the inside and the room’s window barred on the outside. The only evidence of a crime were a bloodied handkerchief, a man’s cap, some muddy footprints, and a large blood-stained handprint on the room’s yellow wallpaper.

How had Mademoiselle Stangerson’s assailant escaped the “Yellow Room”?

Gaston Leroux’s Le Mystère de la chambre jaune (“The Mystery of the Yellow Room”) occupies a canonical position in the development of the closed-room murder mystery novel.[1] Previous locked-room mysteries, such as Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”(1841) and Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Adventure of Speckled Band” (1892), had been short stories. Leroux ran with the idea further by not permitting entrance or exit by means of a secret passageway, and then stretching out the solution to the impossible crime over the course of an entire novel.

Photographic portrait of Gaston Leroux, c. 1920. Criminocorpus.org: Bibliothèque des littératures policières, Paris.

Gaston Leroux was born in Paris in 1868 to Alfred Leroux, a public works contractor, and Marie Bidault, the daughter of a court bailiff. The following month, the couple married and relocated to Rouen in Normandy. Gaston attended Jesuit boarding school at the Collège d’Eu in Upper Normandy and passed his baccalaureate examination in Caen in 1886. He moved to Paris to study law and obtained his license to practice in 1889, but more enjoyed bantering in cafés with literary acquaintances in the Latin Quarter.

In 1893, Leroux became a journalist for Le Matin, one of the four leading daily newspapers in Paris. Fortuitously, he was assigned to its chronique judiciaire criminal court column in 1894. That year, he reported on the trials and executions of “propaganda by the deed” anarchists such as Auguste Vaillant, who threw a bomb into the Chamber of Deputies, and Santo Caserio, who assassinated President Sadi Carnot. He also covered the Procès de Trente (“Trial of Thirty”), a mass trial of criminals and anarchists, including the art critic and anarchist theoretician Félix Fénéon, who were prosecuted together under the recently enacted lois scélérates (“laws against criminal outrages”).

Leroux extended his journalistic reach by moving into international politics, scooping an exclusive interview with the exiled Pretender King Philippe d’Orléans in London and traveling to Russia as member of the French diplomatic press corps. He also tried his hand at writing feuilleton installment novels for Le Matin, beginning with Un Homme dans la nuit (“A Man in the Night,” 1888), a mash-up crime, romance, and avenger novel set in the American West. Next came Le Double vie de Théophraste Longuet (“The Dual Life of Théophraste Longuet,” 1903), in which the spirit of the eighteenth-century bandit Cartouche inhabits the titular character. His third novel, Le Mystère de la chambre jaune, established his reputation as a popular novelist.

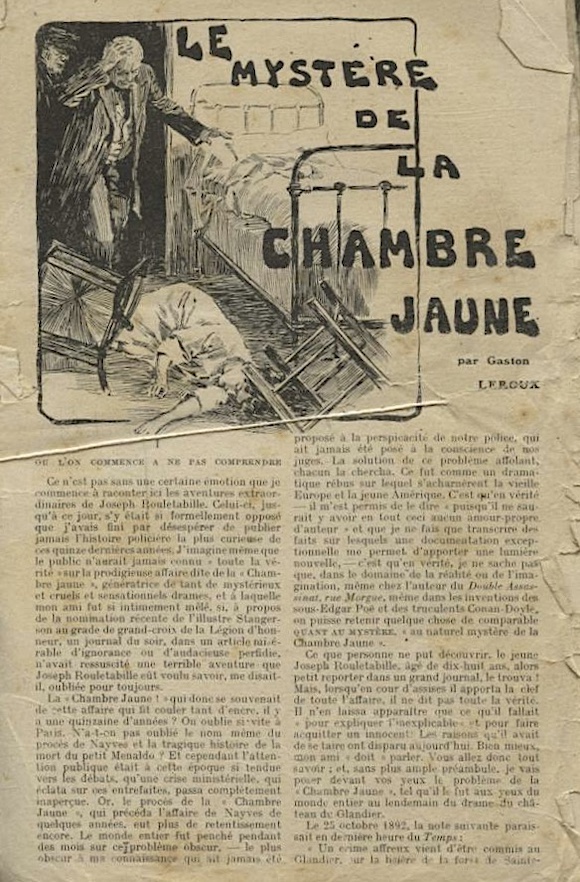

First page of Le Mystère de la chambre jaune, originally published in L’Illustration, 1907. Reissued imprint in Le Dimanche Illustré, c. 1924. Image Source: le-livre.fr.

Following the assassination attempt against Mademoiselle Stangerson, Sûreté Inspector Frédéric Larsan arrives from Paris to conduct the official inquiry. In short order, Larsan fingers Mathilde’s fiancé, Robert Darzac, as the would-be assassin. Also appearing on the scene is Joseph Rouletabille, a young newspaper reporter and amateur detective renowned for his remarkable intellect. Convinced of Darzac’s innocence, Rouletabille conducts a parallel investigation and, in a classic denouement, reveals the culprit’s identity and how the crime was committed.

In the novel’s concluding chapters, Rouletabille makes several disclosures that set the stage for a sequel, Le Parfum de la dame en noir (“The Perfume of the Lady in Black,” 1909). Two decades earlier, Professor Stangerson had been invited to Philadelphia as a scientific researcher, accompanied by his daughter. While in America, Mathilde met and clandestinely married a con man named Jean Roussel, an alias of the internationally notorious criminal mastermind Ballmeyer. After the Strangersons return to France, Ballmeyer learned of Mathilde’s impending marriage to Roger Darzac, and he sent her threatening letters that contained the cryptic phrase:

“The chapel has lost none of its charm, nor the garden its splendor.”[2]

Over the course of Rouletabille’s investigation, he discovered that Roussel already had a wife, and the scoundrel had tricked Mademoiselle Stangerson into wedlock. With the bigamous marriage exposed and annulled, Mathilde was now free to marry Robert Darzac. However, a child was born from the Roussel-Stangerson union… Joseph Rouletabille!

Cover of Le Mystère de la Chambre Jaune, Part 2, Le Secret de Mademoiselle Stangerson. Series “Les Aventures extraordinaires de Joseph Rouletabille.” Illustration by Maurice Toussaint. Paris: Pierre Lafitte, 1920. Author’s Collection.

In Le Mystère de la chambre jaune, Rouletabille would occasionally catch a whiff of a familiar scent that invoked fond memories of his lost mother — whom he now knows is Mathilde. Yet as Ballmeyer’s offspring, his father’s criminal nature comingled with his brilliance as a detective, causing him tremendous anxiety. To complicate matters further, Ballmeyer continues to send threatening letters to Mathilde, demanding she again become his lover, or he would kill her. Consequently, Rouletabille swears to protect his mother from Ballmeyer, to whatever lengths may be required. In Le Parfum de la dame en noir, the detective applies his intellectual acumen not to solve a murder, but to try and prevent one.

At the encouragement of publisher Pierre Lafitte, Leroux went on to write six additional Rouletabille adventures over the next decade.[3] However, he transformed the cerebral detective into an action-adventure hero embroiled in convoluted plots of international espionage, romance, and revenge, instead of using his intellect to solve crimes.

Cover of Le Château noir (“The Black Castle”). Series “Les Aventures extraordinaires de Joseph Rouletabille.” Illustration by Roger Broders. Paris: Pierre Lafitte, 1922. Author’s Collection.

Concurrent with Rouletabille’s later adventures, Leroux launched an equally popular crime series, Chéri-Bibi. Only this time, his protagonist was a criminal-avenger. Initially appearing as a feuilleton novel in Le Matin (1913), Chéri-Bibi tells the story of an innocent man wrongly accused, convicted, and condemned to hard labor for a murder he did not commit. In the tradition of Alexandre Dumas’s Count of Monte Cristo and Ponson du Terrail’s Rocambole, Chéri-Bibi is a remorseless criminal, murderer, and avenger, with no need for redemption. His transgressions are not rooted in a criminal psychology, however, but are the consequence of Cruel Destiny — Fatalitas! A “criminal with a big heart and big dagger,” he is a tragic “everyman” who rebels against insurmountable circumstances that keep him down.[4]

The novel opens with Chéri-Bibi, Prisoner no. 3216, caged with hundreds of other convicts aboard Le Bayard, a transport ship bound for a bagne hard-labor colonial prison in Cayenne.[5] After the redoubtable criminal orchestrates a mutiny against the ship’s commander and crew, the convicts now obey Chéri-Bibi as their captain. Then, during a tempest, the prison transport vessel collides with the passenger liner Belle-Dieppoise, whose survivors are brought aboard. Among them is the Marquis Maxime du Touchais, whose father Chéri-Bibi had been condemned to perpetual hard labor for murdering. Fatalitas!

Inexplicably, the Marquis disappears. Simultaneously, Chéri-Bibi is struck down by a fever and quarantined to the ship’s infirmary by Dr. Kanak, a homicidal cannibal.[6] The surgeon kills Maxime du Touchais, flails his face and hands, and grafts them onto Chéri-Bibi.[7]

Cover of Chéri-Bibi by Gaston Leroux. Illustration by Gino Starace. Collection “Livre Populaire.” Paris: Arthème Fayard, 1914. Author’s Collection.

Reportedly, Chéri-Bibi’s condition worsens; he dies and is buried at sea. Coincidentally, the Marquis du Touchais resurfaces, but something about him strikes La Ficelle, ship’s cook, as odd — a suspicion confirmed by the Marquis’s enthusiasm for la morue à l’espagnole (“Spanish codfish”), Chéri-Bibi’s favorite recipe. As the ship rounds the Horn of Africa, Chéri-Bibi conspires with La Ficelle to arrange the ransom of the Marquis du Touchais. In Cape Town, La Ficelle receives a payoff of six million francs in exchange for for the marquis, which is divvided up among criminal crew on Le Bayard. Skimming off a million for themselves, Chéri-Bibi and La Ficelle give their accomplices the slip and set sail for Normandy.

Arriving at the port city of Dieppe, the Marquis du Touchais (Chéri-Bibi) and his valet Monsieur Hilaire (La Ficelle) read in the Dépêche du Times that Le Bayard was bombarded and sank off the islands of Indonesia, with three-quarters of its pirate crew drowning, including the odious Dr. Kanak. The pair make their way to the Touchais family villa, inhabited by Cécily, Maxime’s wife, and the dowager Marquise du Touchais. At first, Cécily is startled by changes in her previously reserved and emotionally distant husband, who now overflows with affection, smothering her with kisses and doting upon her seven-year-old son, Bernard. Chéri-Bibi and Cécily fall passionately in love, and nine months later she gives birth to a son, Jacques.

Fatalitas! Sûreté Inspector Costaud, who believes Chéri-Bibi faked his death and remains at large, arrives at the villa. Repeatedly, he interrogates Maxime about events on board Le Bayard. Matters are further complicated by the failing health of the elderly Marquise du Touchais. When Dr. Walter is called to the villa to provide medical assistance, Chéri-Bibi recognizes him as… Kanak! And vice versa. The loathsome reprobate blackmails Chéri-Bibi with documents about the facial transplant and false ransom. Chéri-Bibi agrees to a rendezvous to pay off Kanak to the tune of one million francs — but instead plunges a dagger into his adversary’s chest, slashes his throat, and tosses him off a cliff into the sea.

Chéri-Bibi also runs afoul of Monsieur Pont-Marie, a rival suitor for Cécily’s affections. Under duress, Pont-Marie reveals that… Maxime du Touchais murdered his own father! Further, Pont-Marie conspired with Maxime to frame Chéri-Bibi for the homicide. Enraged, Chéri-Bibi forces Pont-Marie into the Marquis de Touchais’s clothing, strangles him with a necktie, and pours sulfuric acid on his face to obliterate its features.

Pondering these revelations, Chéri-Bibi reflects upon the myth of Oedipus:

Last year, Cécily and I saw Oedipus the King… Fate brutally struck him down. He killed his father without knowing it was him! He married his mother without knowing it was her! He was the brother of his own children! He tore out his eyes… and was that the reason he became blind? It depends on how you look at it, because it wasn’t his fault. It was Destiny that wanted him that way! (Chéri-Bibi, p. 307)

Chéri-Bibi considered himself even more miserable than Oedipus: “Fatalitas! I stole the skin of a gentleman, and have become a murderer twice over!” (Chéri-Bibi, p. 325). By killing Maxime and stealing his identity, not only did Chéri-Bibi knowingly engage in an adulterous love with Cécily as her false husband, he assumed the identity an aristocratic prodigal son who committed patricide.

Chéri-Bibi draws to a close with a dinner party hosted at the Chateau du Touchais. As the guests arrive, including Inspector Costaud, they hear blood-curdling screams emanating from the chateau, which has exploded into a blazing inferno. A monstrous figure stands in a doorway, his silhouette illuminated by the flames and face horribly disfigured. His naked chest bears an indelible tattoo, “CHÉRI-BIBI.” With a final cry of “Fatalitas!” he withdraws into the flames. The following morning, the charred corpse of the Marquis du Touchais is recovered, but not that of Chéri-Bibi.

“You think he’s dead?” Inspector Costaud asked. “We’ll talk about that another day” (Chéri-Bibi, p. 338).

Indeed, Leroux resurrected Chéri-Bibi in sequels. In 1918, French actor René Navarre, who starred as the archvillain in Louis Feuillade’s Fantômas silent-film movies (1913-1914), collaborated with Leroux to co-produce a Chéri-Bibi movie saga in sixteen episodes, La Nouvelle Aurore (“The New Dawn,” 1918).

Cover of the first installment of the novel serialization of La Nouvelle Aurore, starring René Navarre as Chéri-Bibi. Les Romans du Cinéma, October 12, 1920. Author’s Collection.

Set in a Cayenne penal colony, Chéri-Bibi befriends a young aristocrat named Palas, wrongly convicted of murder and robbery. Together they escape imprisonment, make their way back to France, and Palas is exonerated. Along the way, once again Chéri-Bibi murders several people. La Nouvelle Aurore proved so popular with audiences that the following year Leroux adapted the film serial into a 110-episode feuilleton published in Le Matin (1919), as well as a sixteen-issue photo-illustrated version in the film magazine Les Romans-Cinéma (1920).[8] In the final novel in the series, Chéri-Bibi, le marchand de cacahouètes (“Chér-Bibi, Peanut Vendor,” 1925), Chéri-Bibi first encourages and then thwarts his son Jacques’s ambitions to become the next Bonapartist Emperor of France.[9]

Why would French readers be drawn to such a violent and murderous character as Chéri-Bibi, much less consider him a hero? The short answer is that, by calling his character Chéri-Bibi, Leroux considered him one. In criminal argot, his name means “dur moi” or “strong me” — a robust, rough, and powerful man.[8] The sobriquet is reinforced by his shouting at the convict mutineers, “Moi! Chéri-Bibi!” (“Me! I’m the strong one!”), who obey him as their captain unquestioningly.

The longer answer is the moniker had gentler origins. As a youth, his sister called her brother Jean, a servant boy, chéri-bibi (“dear strong one”) as a term of endearment, and everyone in the village knew him by that nickname. On his daily delivery route hauling meat from the butcher’s shop, the strapping young Jean would catch a glimpse of the beautiful young Cécily as he passed by her family’s estate. But after the murder of the Marquis du Touchais, and following Jean’s false conviction and brutal punishment for the crime, the former phrase of affection turned into a motto of insurrection. Yet Chéri-Bibi’s revolt is one of an “everyman,” not that a political revolutionary committed to a cause or a justicier social avenger.

In 1927, Gaston Leroux died of complications from kidney failure. By that time, he had become one of France’s most popular authors, best remembered today for Le Fantôme de l’Opéra (“Phantom of the Opera,” 1910). In English translation, The Mystery of The Yellow Room retains a canonical position in the development of the closed-room mystery novel, while Chéri-Bibi barely registers. In contemporary France, Rouletabille and Chéri-Bibi persist in popular cultural memory thanks largely to television and movie adaptations.[10] Once tremendously popular, today the reporter-detective and criminal-avenger are patrimonial figures of French nostalgia.

The Mystery of the Yellow Room by Gaston Leroux. The original English-language edition reprises the original Laffite book cover. New York: Brentano’s, 1908. Author’s Collection.

NOTES

[1] The heyday of cerebral detectives solving closed-room mysteries occurred in Britain and America from the 1920s through the 1950s, most notably those by Edgar Wallace, S. S. Van Dine, Ellery Queen, and Carter Dickson (pseudo. John Dickson Carr). See Donald E. Westlake,“The Locked Room,” in Murderous Schemes: An Anthology of Classic Detective Stories (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

[2] “Le presbytère n’a rien perdu de son charme, ni le jardin de son éclat.” The phrase is invoked several times over the course of Le Mystère de la chambre jaune. English translations throughout this post are by the author.

[3] Subsequent novels in the series “Aventures Extraordinaires de Joseph Rouletabille, Reporter” (Paris: Pierre Lafitte): Rouletabille chez le Tsar (1912), Le Château noir (1916), Les Étranges noces de Rouletabille (1916), Rouletabille chez Krupp (1920), Le Crime de Rouletabille (1923), and Rouletabille chez les Bohémiens (1922). None are translated into English.

[4] Jean-Claude Vareille, L’homme masqué: Le justicier et le détective (Lyon: Presses universitaires de Lyon, 1989), p. 97; and, Alfu, p. 11.

[5] Chéri-Bibi is a novel in two parts: Les cages flottantes (“The Floating Cages”) and Cécily. Only the first was translated into English and abridged as Wolves of the Sea (New York: Macaulay, 1923; a.k.a. The Prison Ship, London: T. W. Laurie, 1923). Without reference to a more complete source for English readers, I have summarized the entire novel in this post.

[6] In racist imperial lore, the indigenous Kanak people of New Caledonia, a French Pacific colony, are “cannibals.” Leroux makes the connection to Dr. Kanak explicit.

[7] In an extensively fabricated footnote, Leroux details the procedure supposedly developed by Dr. Alexis Carrel, renowned French vascular surgeon, pioneer in organ transplants, member of the American Medical Association, and recipient of 1912 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Gaston Leroux, Chéri-Bibi, pp. 167-168.

[8] La Nouvelle Aurore is abridged in English translation as The Dark Road: Further Adventures of Chéri-Bibi (Cleveland: The Goldsmith Publishing Co., 1924).

[9] Originally published as a feuilleton in 81 espisodes in Le Matin (July-October 1925); revised and published as Le Coup d’État de Chéri-Bibi (Paris: Baudinière, 1926).

[10] S.v. “bibi” and “cher, ère” in Dictionnaire de l’argot (Paris: Larousse, 1990).

[11] Most recently: Chéri-Bibi, directed by Jean Pignol, starring Hervé Sand, television serial in 46 episodes (ORTF, 1974-1975; DVD reissue, INA/LCJ Éditions, 2001); Le Mystère de la chambre jaune, directed by Bruno Podalydès, starring Denis Podalydès (Why Not Productions/France 2 Cinéma, 2003); and, Le Parfum de la dame en noir, directed by Bruno Podalydès, starring Denis Podalydès (Why Not Productions/France 2 Cinéma, 2005).

SOURCES

Alfu (pseudo. Alain Fuzellier), Gaston Leroux: Parcours d’une œuvre (Amiens: Encrage, 1996).

Gaston Leroux, Chéri-Bibi, collection “Bouquins” (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1990).

_____. Rouletabille, eight novels in 4 vols. (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1961-1963).

_____. The Mystery of the Yellow Room: The Extraordinary Adventures of Joseph Rouletabille, Reporter (New York: Brentano’s, 1908).

_____. The Perfume of the Lady in Black, trans. Margaret Jull Costa (Cambridge, UK: Dedalus Ltd., 1998).

Updated: January 6, 2026

Robin Walz © 2025

Leave a comment