Cover of Arsène Lupin, Gentleman Cambrioleur (“Gentleman Burglar”). Éditions Pierre Lafitte, 1914 (reissue 1921). Illustration by Léo Fontan. Author’s Collection.

By 1905, author Maurice Leblanc had hit upon hard times. Born in 1867 to a privileged bourgeois family from Rouen in Normandy, Maurice was well poised to become a literary celebrity. Renowned novelist Gustave Flaubert was a family friend. His sister Georgette was an accomplished actress and opera singer, as well as the lover of the renowned Belgian playwright Maurice Maeterlinck. Despite his businessman father’s desire for him to become a lawyer, young Maurice moved to Paris in 1885 to become a famous writer.

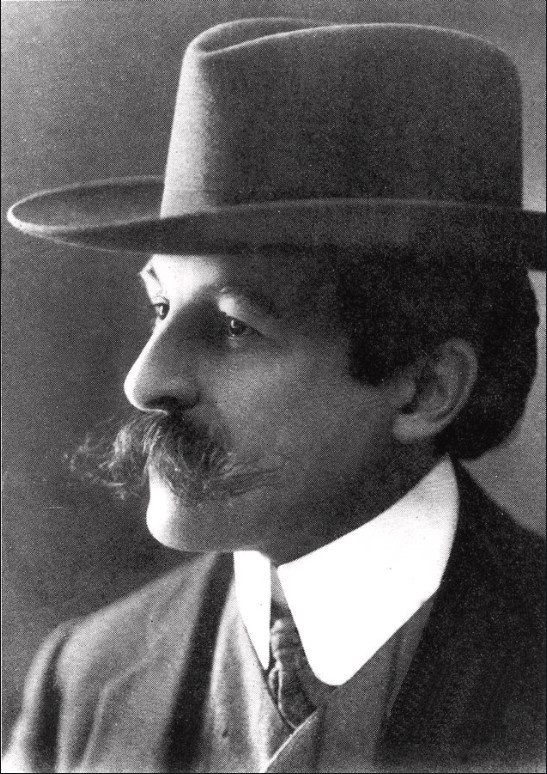

Frontispiece portrait of Maurice Leblanc, in Arsène Lupin, Gentleman: Cambrioleur, Pierre Lafitte & Co., 1907. Photograph by Henri Manuel. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In short order, Leblanc was writing columns and short stories for a variety of journals, including Gil Blas, the fashionable literary magazine that helped launch the careers of Guy de Maupassant and Émile Zola. In 1893, Gil Blas serialized Leblanc’s first novel, Une Femme (“A Woman”). Along the lines of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, Leblanc spun a tragic tale about the vacuous lives of provincial bourgeoise women who pursue illusory joys through romantic liaisons. The serial enjoyed moderate success and was published as a novel the same year.

Cover of Gil Blas promoting the first installment of Maurice Leblanc’s Une Femme, April 9, 1893. Illustration by Steinlen. Wikimedia Commons: Digital Public Library of America, Boston Public Library.

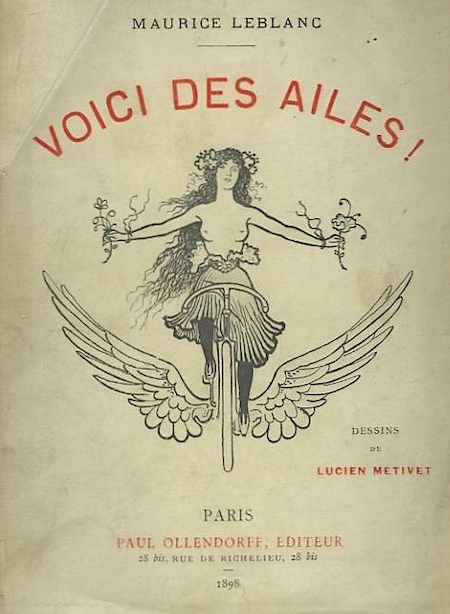

His subsequent novels floundered, however. Voici des ailes! (“These are Wings!” 1897), about the emancipation felt by modern and sexually liberated young men and women who “fly” across Normandy and Brittany by bicycle, was a flop. In the prestigious literary review Mercure de France, eminent woman of letters Rachilde savaged it as a roman snobique (“a novel for snobs”).[1] Enthousiasme (“Enthusiasm,” 1901), Leblanc’s fictionalized autobiography about the joys of provincial life, was panned by critics as well. Although he continued to write short stories for various literary magazines and joined the Société des Gens de Lettres writers’ mutual aid association, Leblanc was slipping into obscurity.

Cover of Voici des Ailes! Published in book format by Paul Ollendorff, Éditeur, 1898. Image Source: Chroniques Terriennes Blog.

Then, his fortunes took a turn. In February 1905, nouveau publisher Pierre Lafitte launched Je sais tout (“I Know Everything”), an illustrated monthly magazine whose articles ranged from national and international events to coverage of the arts, literature, music, science, and sports, as well as original poetry, short fiction, and serialized novels. To broaden readership, Lafitte sought a detective or criminal character that could bring his magazine the kind of popular and financial success that Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories had given The Strand Magazine.[2] Laffitte’s finance and publicity officer Marcel L’Heureux suggested that his friend, Maurice Leblanc, could deliver the goods.

Cover of Je sais tout, no. 2, March 15, 1905. Illustration by Jules-Alexandre Grün. Wikimedia Commons: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Leblanc’s short story, “L’Arrestation d’Arsène Lupin” (“Arsène Lupin Arrested”), appeared in the July 15 issue of Je sais tout. The story revolves around jewelry thefts committed on the ocean liner Provence by Monsieur R—, an alias of Arsène Lupin. Sûreté Inspector Ganimard, who for years has pursued but failed to capture Lupin, is aboard as well, seeking to ferret out and arrest the mysterious Monsieur R—. Leblanc thought the short story would be a one-off.

But the entrepreneurial Lafitte proposed that an entire series of Arsène Lupin adventures should follow. Leblanc, who considered himself a literary author, initially resisted, insisting he did not want to be limited to writing popular fiction. Lafitte responded that Leblanc had more than enough talent to quickly knock out Arsène Lupin stories with a minimum of effort, affording plenty of time for more cultured pursuits. Besides, it was easy money. In dire financial straits at the time, Leblanc accepted the offer.

In November 1905, Je sais tout announced a forthcoming series of “surprising, mysterious, unexpected, original and exciting adventures by the brilliant crook, ARSÈNE LUPIN.”[3] Proclaiming Maurice Leblanc the French Arthur Conan Doyle, the monthly short stories were issued under the series title, “La vie extraordinaire d’Arsène Lupin” (“The Extraordinary Life of Arsène Lupin,” December 1905-July 1906). To stir up reader excitement, the magazine ran a concours (contest) each issue, requesting readers submit written responses to questions that anticipated the next installment, with promises of monetary prizes.

“How will Arsène Lupin escape?”

“Who will be the next victim of Arsène Lupin?”

“What historical jewel, already made famous in a celebrated affair, will Arsène Lupin steal?”

“What renowned detective will Arsène Lupin measure himself against?”[4].

Winnings for the best responses were substantial; first prize 500 francs, second prize 100 francs, third prize 50 francs. The Arsène Lupin series was an instant hit with readers and a financial boon for Laffite.

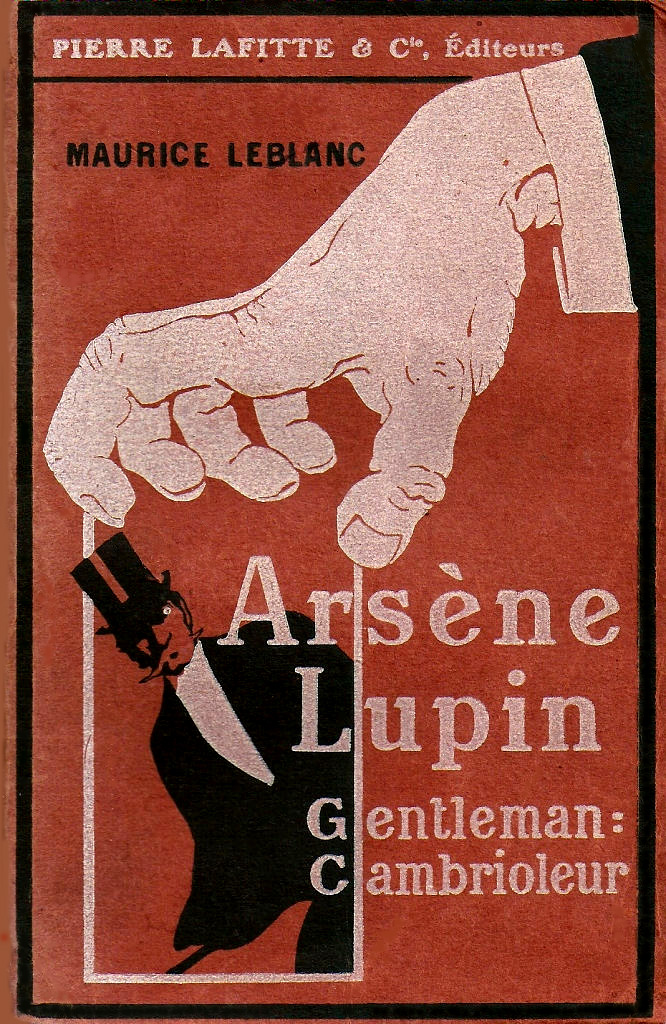

The initial collection of short stories published in book format as Arsène Lupin, Gentleman: Cambrioleur, Pierre Lafitte & Co., 1907. The cover design by Henri Goussé depicts Lupin evading the grasp of the Law. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons.

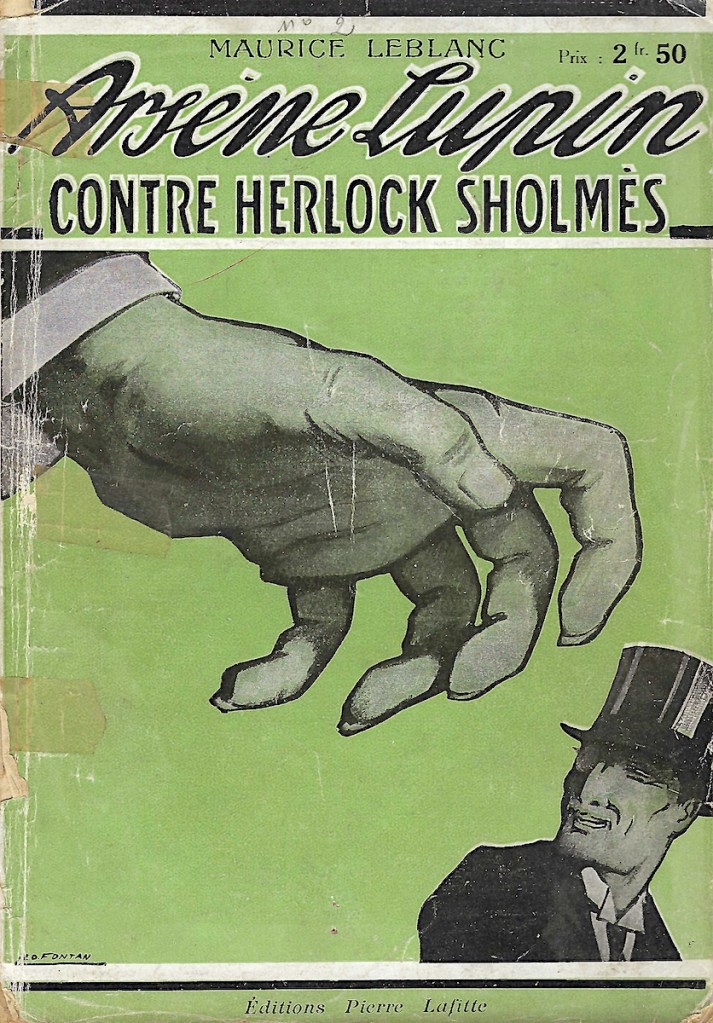

The following year, Leblanc delivered on the promise to become the French Conan Doyle with “Les nouvelles aventures d’Arsène Lupin” (“The New Adventures”), in which in which the gentleman thief mocks and outwits Sherlock Holmes. The move had been foreshadowed in a short story from the initial series, “Sherlock Holmes arrive trop tard” (“Sherlock Holmes Arrives Too Late”).[5] In “La Dame blonde” (“The Blonde Woman”) and “La lampe juive” (“The Jewish Lamp”), serialized in Je sais tous (November 1906-October 1907), Inspector Ganimard invites “Herlock Sholmes” to Paris to capture Arsène Lupin once and for all. Instead, the British sleuth is outfoxed by his clever French criminal counterpart. Laffite quickly reissued the stories as Arsène Lupin contre Herlock Sholmes (1908).

Cover of Arsène Lupin contre Herlock Sholmès, depicting the French criminal evading the grasp of the British sleuth. Éditions Pierre Lafitte, 1914 (reissue 1924). Illustration by Léo Fontan. Author’s Collection.

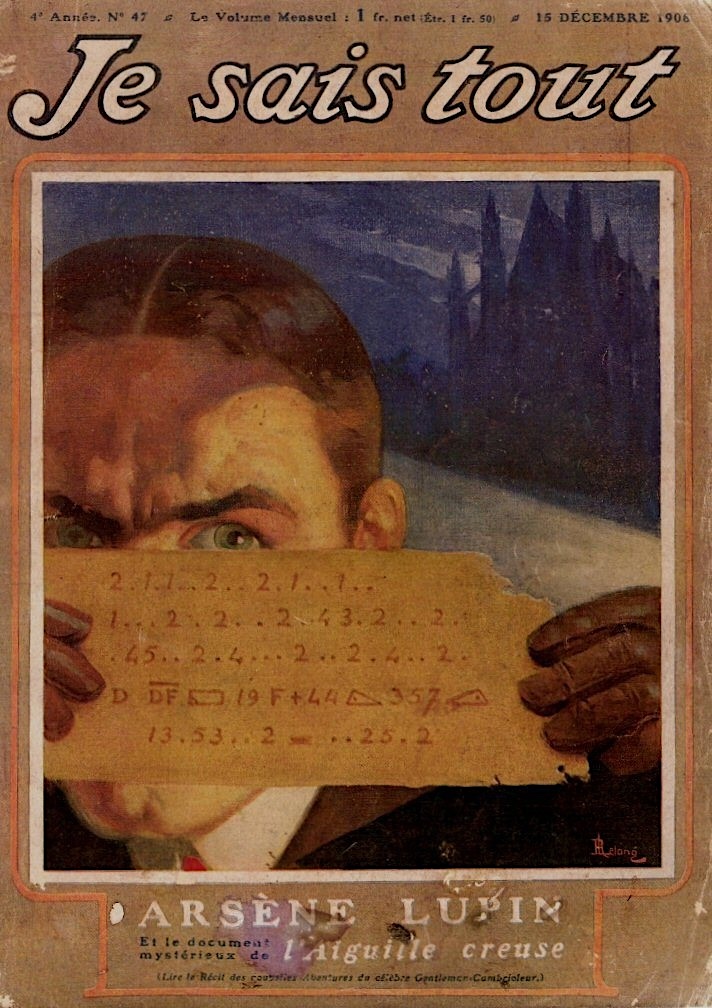

The following year, Leblanc wrote his first full-length Arsène Lupin novel, L’Aiguille creuse (“The Hollow Needle”), serialized in Je sais tout (November 1908-May 1909) and immediately reissued as a book. Set in the town of Étretat in Normandy, the Hollow Needle is an iconic rock formation along the sea cliffs. In the novel, Lupin demonstrates his intellectual prowess by decoding a cryptogram that proves key to solving the story’s mystery.

Cover of Je sais tout, no. 47, December 15, 1908, featuring the first installment of the serialized Arsène Lupin novel, L’Aiguille creuse. Illustration by René Lelong. Wikimedia Commons: Arsène Lupin et les autres Blog.

Whether as a mastermind criminal, justicier avenger, or shady detective, Arsène Lupin possesses a common set of traits. Foremost, he is entertainingly clever, continually taunting, outsmarting, and evading his law-and-order counterparts. He also exhibits intellectual brilliance to a nearly supernatural degree, whether devising intricate criminal scenarios to benefit himself, escaping from impossible situations, or foiling the nefarious plans of others. He is generous sharing his talents on behalf of others, yet will blackmail clients for financial gain when that entails preserving their social reputation under delicate circumstances. Above all, Arsène Lupin emanates self-confidence and humor, always ready with a witty quip and willing to take tremendous risks for the sheer pleasure of doing so.

Arsène Lupin’s identity, however, is fluid. He nearly always appears as someone else, an aspect Leblanc wrote into the character from the start:

“His likeness? How can I trace it? I have seen Arsène Lupin a score of times, and each time a different being has stood before me….”[6]

In the original Arsène Lupin, gentleman-cambioleur collection, his aliases include Viscount Raoul d’Andrésy, Count Bernard Andrézy, clochard tramp Désiré Baudru, mysterious train passenger Guillaume Berlat, the Italian Chevalier Floriani, former Sûrete Inspector Grimaudan, the magician Rostat, Russian Prince Serge Rénine, and celebrated seascape painter Horace Velmont. Over thirty years of adventures, Arsène Lupin was equally at ease playing upper-class roles as aristocrats, mondain high-society dandies, foreign dignitaries, members of the business and professional elite, police officers and private detectives, and engaging in everyday occupations such as a jeweler, housepainter, boxing instructor, fireman, or simply being “a friend of Maurice Leblanc.”[7]

Behind these multiple identities, the question remains: who is Arsène Lupin? Leblanc first raised the issue in “Comment j’ai connu Arsène Lupin” (“How I knew Arsène Lupin,” 1907), without providing a direct answer.[8] It wasn’t until 1924, after nearly two decades of Arsène Lupin adventures, that Leblanc finally provided his hero with a definitive origin story in La Comtesse de Cagliostro (“Countess Cagliostro”).[9] In this doomed-romance adventure novel, Arsène-Raoul Lupin is the son of Henriette d’Andrésy, the daughter of Normandy aristocrats who, against their will, married Théophraste Lupin, a gymnast, boxer, fencing instructor, and con man. He emulated his mother’s aristocratic sensibilities as the Viscount Raoul d’Andrésy, yet retained his father’s physical adeptness and prowess in dissimulation as Arsène Lupin.

Cover of La Comtesse de Cagliostro representing Arsène Lupin’s dual-inheritance, with the nobility of his aristocratic mother foregrounded and the shadow of his con-man father lurking behind. Illustration by Roger Broders. Éditions Pierre Lafitte, 1924. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Occasionally, Leblanc strove to invent new, and hopefully equally profitable, characters and series beyond Arsène Lupin, but none worked out. In 1925, Lafitte published Leblanc’s La Vie extravagante de Balthazar (“The Astonishing Life of Balthazar”), a kind of contemporary corollary to Voltaire’s Candide, but the book sold poorly. Some of Leblanc’s other titles would be published with the disclaimer that one or another of the principal characters was actually Arsène Lupin. In the romance and adventure novel, La demoiselle aux yeux verts (“The Young Lady with Green Eyes,” 1927), Baron Raoul de Limézy avenges the murder of Englishwoman Lady Constance Bakefield. Leblanc amended the opening chapter to reveal that Limézy was really Arsène Lupin, assuring readers that the novel was still about their favorite character.

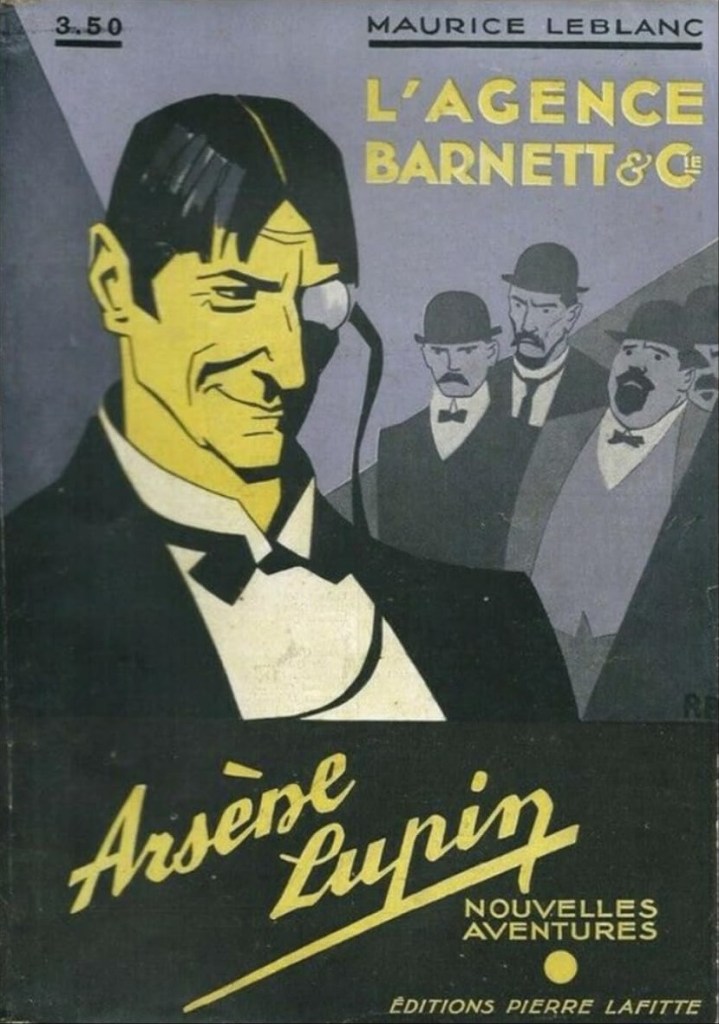

Leblanc also submitted three short stories about a shifty private detective named Jim Barnett, “a new character, worthy of the famous gentleman thief,” to Hachette’s monthly magazine Lecteurs pour tous (“Stories for Everyone”).[10] With five additional stories added to the book collection L’Agence Barnett et Cie (“Barnett & Co., Detective Agency,” 1928), publisher Lafitte included a prefatory note:

“We hasten to render to Cesar what is due to Cesar, and to attribute the misdeeds of Jim Barnett to the one who committed them, that is, to the incorrigible Arsène Lupin.”[11]

Leblanc’s celebrity and income were tied to Arsène Lupin, no matter how much he wished otherwise.

Cover of L’Agence Bartnett et Cie. Illustration by Roger Broders. Éditions Pierre Lafitte, 1928. Notably, “Arsène Lupin, Nouvelles Aventures” is displayed more prominently than the book’s title. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Leblanc’s final adventure for the gentleman thief was Les Milliards d’Arsène Lupin (“Arsène Lupin’s Billions,” 1939). Under the guise of Horace Velmonty, Lupin conspires with Allô-Police (“Hello, Police”) magazine director and his secretary to steal Arsène Lupin’s fortune. After long years of absence, Inspector Ganimard resumes his pursuit of Lupin. By this point, Leblanc was so tired of the Lupin series that this final installment amounted to parody of his own work.[12] Two years later, Leblanc died of complications from pulmonary congestion on November 6, 1941.

Yet if Leblanc could not escape Arsène Lupin, the same was not true for his character, who has been continually reinvented across mass media and transnationally for more than a century. Immediately adapted for the stage by playwright Francis de Croisset and Leblanc as Arsène Lupin in 1909, a dozen silent films produced in France and internationally were released over the next decade. Sound movies followed, although most French viewers remember the character through the Arsène Lupin television series starring Georges Descrières (26-episodes, 1971).[13] Arsène Lupin short stories have enjoyed a widespread international distribution as well, translated into more than three dozen languages.[14]

Cover of Lupin III, Greatest Heists by Monkey Punch (pseudo. Kazuhiko Kato), translated by Adrienne Beck (Seven Seas Entertainment, 2021). Author’s Collection.

In the twenty-first century, the transnational adventures of Arsène Lupin have taken center stage. Leading the way is the Japanese manga character Lupin III, the grandson of Arsène Lupin, a master-of-disguise thief and romantic avenger. First created by Monkey Punch in the 1960s, Lupin III has grown in popularity internationally since the 1980s through anime films, cartoons, and video games. Sherlock, Lupin & Me by Irene Adler is a seventeen-volume youth fiction series (2011-2020), written in Italian and translated into French and Spanish, with four episodes in English.[15] In 2021, Netflix produced the television series Lupin, starring Omar Sy as Assane Diop, a contemporary French criminal-avenger whose escapades are inspired by Arsène Lupin.[16]

More than a century after his appearance, Arsène Lupin has become a French national icon, handed down from generation to generation. His short story exploits continue to be read in French schools, and elsewhere they are assigned in intermediate French language classes. In comparison to the other Belle Époque Terribles, such as reporter-detective Rouletabille, criminal avenger Chéri-Bibi, and the archvillain Fantômas, by far Arsène Lupin enjoys the longest and greatest popular legacy, within France and around the globe.

NOTES

[1] Quoted in Jacques Derouard, Maurice Leblanc: Arsène Lupin malgré lui (Paris: Librarie Séguier, 1989), p. 200. This is the principal source about Leblanc’s life and career used in this post. Author’s translations throughout, unless credited otherwise.

[2] Sherlock Holmes stories had been spottily translated into French at the end of the nineteenth-century, beginning with the Countess Jeanne Louise Marie de Polignac (a.k.a. Jane Chalençon) in La marque des quatre: roman anglais (“The Sign of Four,” Hachette, 1896). The earliest collection of Holmes short stories in French conserved by the Bibliothèque nationale de France is Aventures de Sherlock Holmes (Juven, 1904).

[3] Je sais tout, vol. 10 (November 15, 1905): 512.

[4] “Premier concours Arsène Lupin: Comment Arsène Lupin s’évadera-t-il?” Je sais tout, vol. 11, December 15, 1905, p. 672. The translated questions come from the subsequent issues, through May 1905. Although the names of contest winners were not published in Je sais tout, Lafitte promised readers they would be included in separate feuillets de garde (“endpapers”), after the conclusion of the sixth and final concours.

[5] After Conan Doyle threatened to sue for copyright infringement, in subsequent Arsène Lupin publications Laffite modified the British sleuth’s name as “Herlock Sholmes.” This remained in effect until 2011 with the expiration rights of the Conan Doyle’s heirs to the Sherlock Holmes character name. See Colin Schultz, “‘Sherlock Holmes’ is Now Officially Off Copyright and Open for Business,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 19, 2014.

[6] “Son portrait? Comment pourrais-je le faire? Vingt fois j’ai vu Arsène Lupin, et vingt fois c’est un être différent qui m’est apparu….” In Maurice Leblanc, “L’arrestation d’Arsène Lupin,” Arsène Lupin, gentleman-cambrioleur, vol. 1 Les aventures d’Arsène Lupin, gentleman-cambrioleur (Paris: Hachette/Gallimard, 1961), p. 295; English translation, “The Arrest of Arsène Lupin,” Arsène Lupin, Gentleman-Thief (New York: Penguin Classics, 2007), p. 17.

[7] The muliple identities of Arsène Lupin are listed under “Les noms de Lupin” in Didier Blonde, Les Voleurs de visages. Sur quelques cas troublants de changement d’identité: Rocambole, Arsène Lupin, Fantômas, & Cie (Paris: Éditions Métalié, 1992), pp. 145-150.

[8] Preface to “Le sept de cœurs” (“The Seven of Hearts”), Je sais tout, no. 27 (May 15, 1907): 489-507.

[9] La Comtesse de Cagliostro was serialized in Le Journal, December 10, 1923 to January 30, 1924, and issued in a single volume by Lafitte in 1924. This novel has recently been published in English: Maurice Leblanc, Asène Lupin vs. Countess Cagliostro, trans. Jean-Marc Lofficier and Randy Lofficier (Encino CA: Black Coat Press, 2010).

[10] “Un nouveau personnage, digne du fameux cambrioleur,” quoted in Derouard, p. 481.

[11] “Aujourd’hui… hâtons-nous de rendre à César ce qui est dû à César, et d’attribuer les méfaits de Jim Barnett à celui qui les commit, c’est-à-dire à l’incorrigible Arsène Lupin.” In L’Agence Barnett et Cie, vol. 4 of Les aventures d’Arsène Lupin, gentleman-cambrioleur (Paris: Hachette/Gallimard, 1961), p. 498; and, Derouard, p. 481.

[12] Les Milliares d’Arsène Lupin, serialized in L’Auto, January 10-February 11, 1939. Reissued as a book in Hachette’s “L’Énigme” collection (1941), it is not included in the “definitive” collection compiled in Les Aventures d’Arsène Lupin, gentleman cambrioleur, 8 vols. (Paris: Hachette/Gallimard, 1961-1962).

[13] See, Jacques Baudou, “Filmographie lupinienne,” Enigmatika no. 2, “Dossier Arsène Lupin” (1976): 39-40; Les aventures d’Arsène Lupin, directed by Jacques Becker, written by Albert Simonin and Jacques Becker, starring Robert Lamoureux (France, 1956, 104 minutes); and, Arsène Lupin, 26 episodes, directed by Jean-Pierre Decourt, starring Georges Descières (Pathé Télévision, 1971).

[14] According to the OCLC WorldCat database, Arsène Lupin, gentleman-cambrioleur has been translated from French into nine European languages, as well as Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Arabic, and Armenian. Language-based Wikipedia sites add an additional twenty-one European, Middle Eastern, South and Southeast Asian languages to that list. Given that paperback imprints are poorly conserved by major library repositories, and Wikipedia pages are authored by devoted enthusiasts, likely the global reach of Arsène Lupin short stories extends to even more languages.

[15] Irene Adler (pseudo. Alessandro Gatti), Sherlock, Lupin e io, 17 vols. (Milan: Edizioni Piemme, 2011-2020). All seventeen books in the series have been translated into French and Spanish, with the first four books translated into English by Nanette McGuinness.

[16] For convergences and departures between Assane Diop and Arsène Lupin in the Netflix Lupin series, see Robin Walz, “‘Vu et regardé’: Lupin Steals the Show,” Imaginairies: Films, Fictions, and Other Representations of French-Speaking Worlds, 12 no. 2 (May 2022).

Updated: October 30, 2025

Robin Walz © 2025

Leave a comment