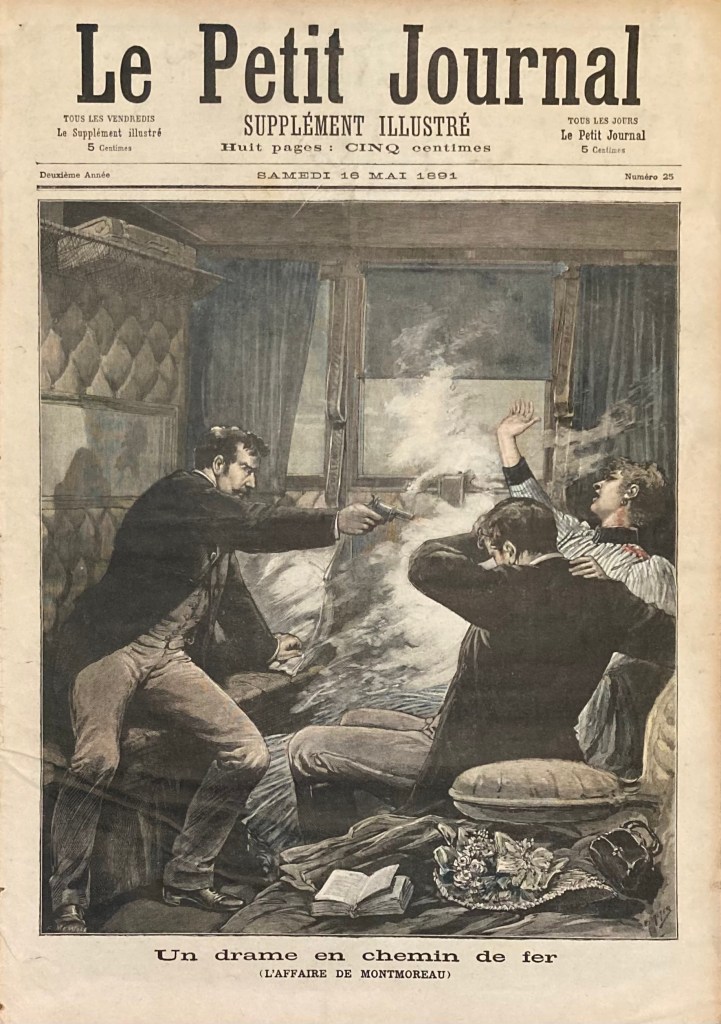

“A Railway Drama: The Montmoreau Affair.” In Le Petit Journal, Supplément Illustré, Saturday, May 16, 1891. Author’s collection.

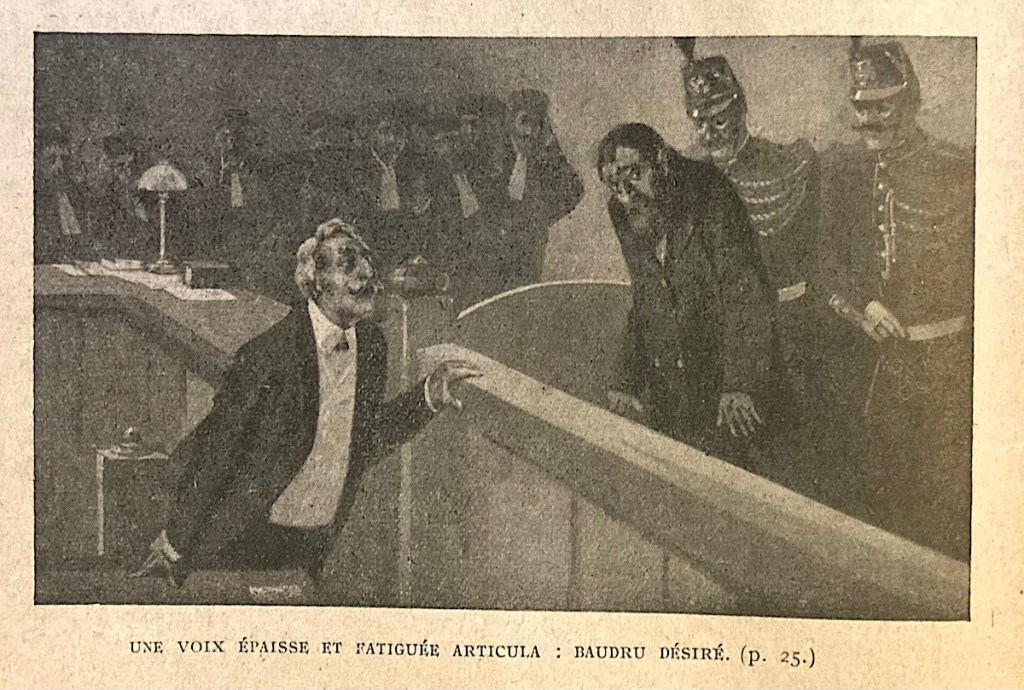

From his prison cell, the celebrated “gentleman burglar” Arsène Lupin had been taunting Sûreté Inspector Ganimard for several weeks.[1] Charged with multiple counts of grand theft, Lupin declared he would not be attending his trial. When the court date finally arrived, the presiding judge asked the man in the dock to identify himself. The prisoner answered, “Désiré Baudru.” Infuriated by this response, the prosecutor berated the accused and insisted he was actually Arsène Lupin. When the man continued to maintain he was Baudru, Inspector Ganimard was brought into the courtroom to verify the man’s identity. To everyone’s great surprise, the Sûreté inspector confirmed this was not Arsène Lupin, but a vagrant called Désiré Baudru. Obviously not guilty of the thefts attributed to Arsène Lupin, the wrongly imprisoned Baudru was released.

“A slow-witted and tired-out voice declared: ‘Désiré Baudru’.” Illustration in Maurice Leblanc, Arsène Lupin, Gentleman Cambrioleur, collection “Les Romans d’Aventure et d’Action” (Paris: Éditions Pierre Lafitte, 1914). Author’s collection.

Perplexed, Inspector Ganimard took a stroll through the Bois de Bologne to gather his thoughts. Sitting down on a park bench, to his amazement Arsène Lupin appeared and took a seat beside him. Lupin informed the inspector that he had encountered Baudru the previous year and had noted similarities in appearance between them. Following his arrest, Lupin bribed the anthropometric technician during intake processing to falsify the first measurement recorded on his identity card. This initial error threw off Bertillon’s entire criminal recidivist system and rendered his card useless. At the last minute before the trial, Lupin substituted the vagrant for himself in the prison cell, momentarily deceiving both the police and the court. Bidding farewell to Ganimard, Arsène Lupin excused himself to attend a dinner party at the British Embassy.

For centuries, outwitting the police had been a common motif in French popular crime stories. From the seventeenth-century forward, apocryphal stories and jargon dictionaries in bibliothèque bleue chapbooks glorified the mysterious lives of vagabonds, rogues, “Gypsies,” and the criminal underworld. In the eighteenth-century, the actual bandit Cartouche and highwayman Mandrin were transformed into popular heroes. In the nineteenth century, Rocambole by Ponson du Terrail and Les Habits noirs by Paul Féval celebrated the exploits of criminal and avenger anti-heroes in sprawling feuilleton novels.

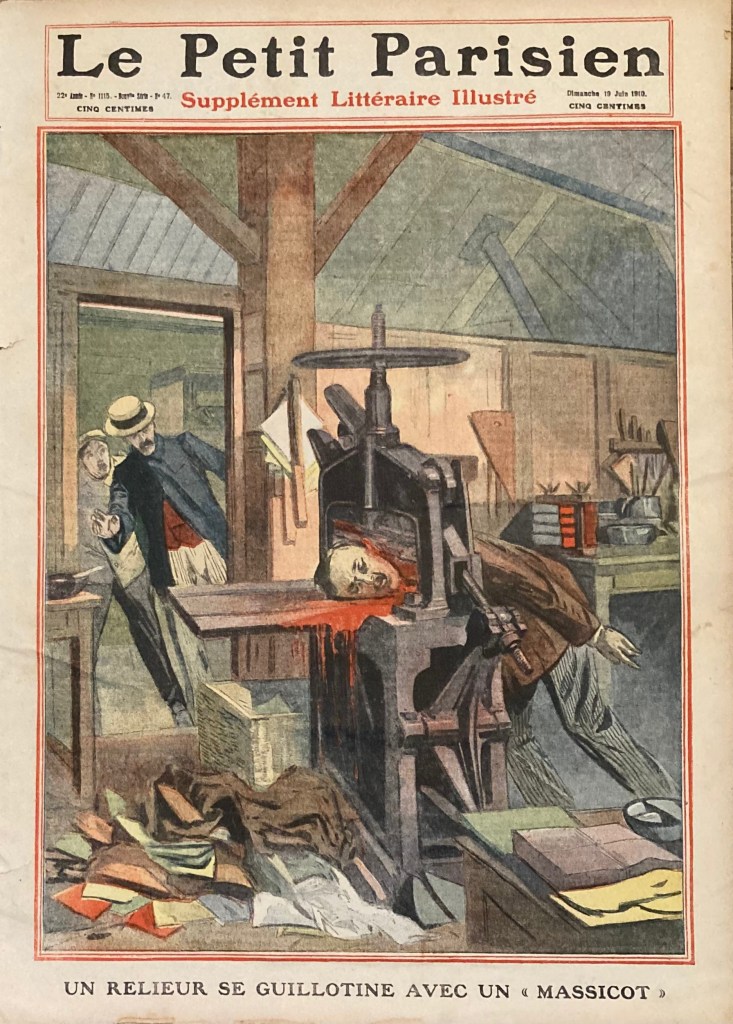

During the Belle Époque transition from the nineteenth to the twentieth centuries, crime stories became a mass-culture phenomenon. For most of the nineteenth century, canards sanglants (“bloody broadsheets”) recounted murders and other violent crimes for readers across the social spectrum, while books of causes criminels célèbres(“famous criminal cases”) compiled scores of criminal transgressions for a bourgeois reading audience. Towards the end of the century, Article 68 of the Law of 29 July 1881 granted an unprecedented degree of freedom of the press to French publishers. As a consequence, the pace and magnitude of reported and fictional crime stories in daily newspapers and magazines soared.

The greatest newspapers of Belle Époque Paris — Le Petit Parisien, Le Petit Journal, Le Journal, and Le Matin — featured sensational crime stories on their front pages. Sold by the issue in kiosks or by street hawkers for a sou (a five-centime coin, roughly a penny), these quatre grands (“big four”) comprised three-quarters of the nearly five million newspapers sold daily in Paris. Weekly newspaper supplements, illustrated in full color, magnified those crime stories.

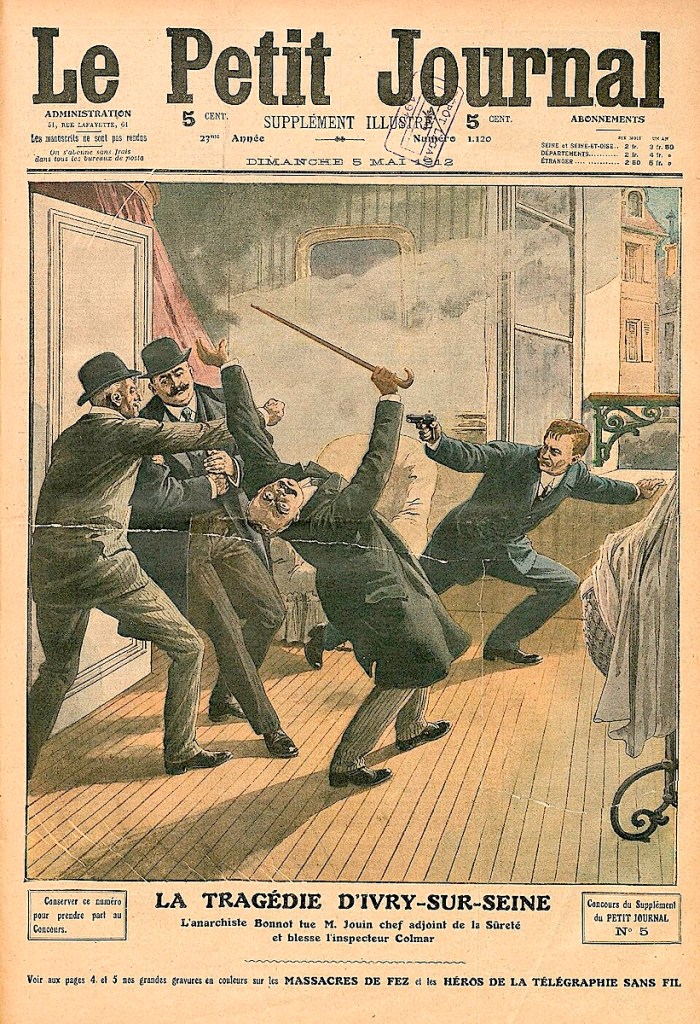

“The Ivry-sur-Seine Tragedy: The Anarchist Bonnot kills Sûreté Deputy Chief Jouin and Wounds Inspector Colmar.” Le Petit Journal, Supplément Illustré, Sunday, May 5, 1912. Gallica: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

If a crime story was sensational enough, it could run in newspapers and weekly supplements for weeks or even months. Coverage of the more notorious criminal trials from the Belle Époque included the gigolo and courtesan killer Enrico Pranzini (1887), “Red Widow” murderess Meg Steinheil (1890), serial killer of children Joseph Vacher (1898), the bande à Bonnot gang of anarchists (1912), and Madame Caillaux’s “crime of passion,” shooting and killing newspaper editor Gaston Calmette (1914).[2] Such outrageous crimes were the exception, however. Far more common, in both in daily newspapers and their supplements, were faits divers, everyday stories about crimes peppered with disturbing details and luridly illustrated.

“A Bookbinder Guillotines Himself with a Paper Cutter.” Le Petit Parisien, Supplément Littéraire Illustré, Sunday, June 19, 1910. Author’s collection.

The commercial possibilities for transforming spectacular crime into popular fiction were not lost on publishers and authors. In the nineteenth century, the most common way for crime writers to reach a wide reading public was through feuilletons — installment novels issued over periods of weeks, months, or even years in newspapers and magazines. To increase profits, publishing firms such as Calmann-Lévy, Charpentier, Flammarion, Albin Michel, and Jules Rouff would reissue feuilleton novels in their entirety, as books for readers who could afford them or in a series of booklets at a reduced price per issue for the less affluent.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, entrepreneurial French publishers began to pioneer new marketing methods. In the late-nineteenth century, bound novels typically sold for 3.50 francs in runs of 5,000 copies or fewer. As an alternate strategy to generate greater profits, parvenu publishers such as Joseph Ferenzi, Jules Tallandier, Pierre Lafitte, and Arthème Fayard cut book prices drastically to one franc or less, and would sell copies in the tens and even hundreds of thousands. The boldest among them was Arthème Fayard II, who launched Le Livre Populaire (“Popular Book”) collection in 1905, a selection of complete novels 300 pages or more in length that sold for 65 centimes each. The initial Livre Populaire collection of nearly one hundred titles were reissues of popular nineteenth-century feuilletons, including the crime and avenger series Rocambole by Ponson du Terrail and Les Habits Noirs by Paul Féval, and the Monsieur Lecoq detective novels by Émile Gaboriau.

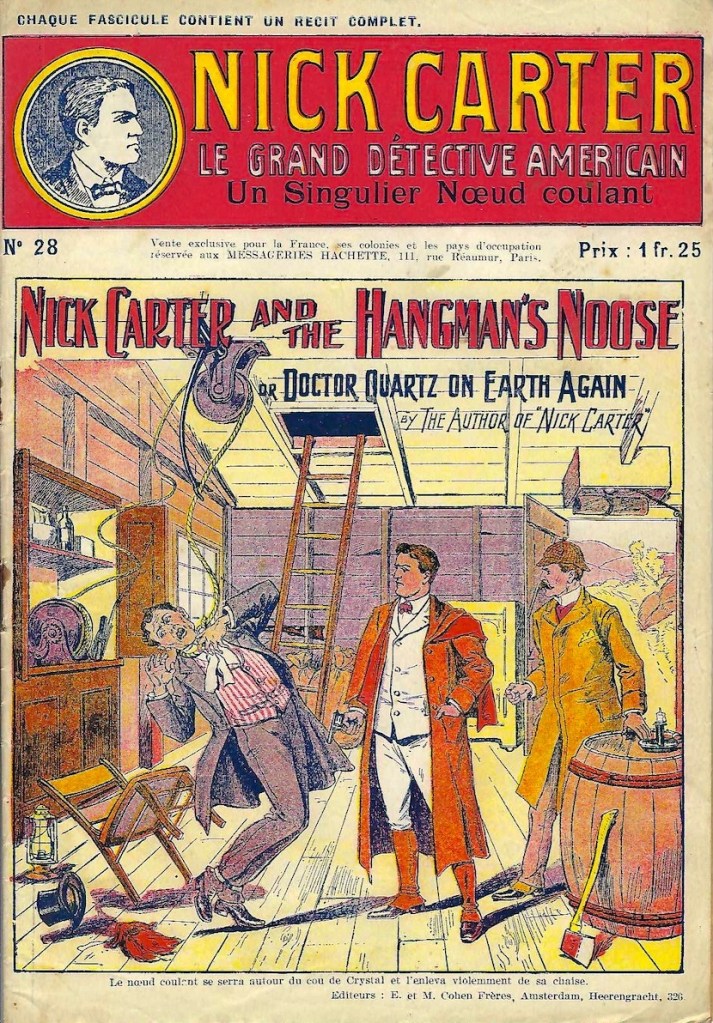

Un Singulier Nœud coulant (French adaptation of Nick Carter and the Hangman’s Noose). Series “Nick Carter, le grand détective américain,” no. 28 (orig. 1907; reissue c. 1920). Author’s collection.

When it came to new crime and detective fiction, Nick Carter, le grand détective américain (“the great American detective”) and Nat Pinkerton, le plus illustre détective de nos jours (“the most famous detective today”) led the way. The adventures of fictional American detectives Nick Carter and Nat Pinkerton were published in fascicules, multi-chapter stories cheaply printed in a magazine format, each thirty-two pages in length and priced at 10 centimes per issue. Each title promised to yield a recit complet (“complete story”), although their adventures were published serially for a combined total of nearly 600 episodes over seven years, 1907-1914.[3] Le Livre Populaire publisher Arthème Fayard took note and upped the ante by publishing entirely new book series, with each volume over 300 pages in length and still priced at 65 centimes. The premier series in Fayard’s revamped popular book collection was Fantômas by Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain, which ran consecutively for thirty-two months from February 1911 through September 1913.

Les Terribles by Antoinette Peské and Pierre Marty (1951). The cover features the Belle Époque criminal and detective characters Fantômas, Arsène Lupin, and Rouletabille. Author’s collection.

In 1951, French novelist Antoinette Peské and her husband Pierre Marty co-authored Les Terribles (“The Terrible Ones”), a survey of four popular heroes and antiheroes from the Belle Époque: gentleman-burglar Arsène Lupin, reporter-detective Joseph Rouletabille, criminal-avenger Chéri-Bibi, and the archvillain Fantômas. While conceived in the twilight of the Belle Époque, these detective, criminal, and avenger characters enjoyed an enduring popularity in France through book and magazine reprints, movies, comics, and on television across the twentieth century and into the twenty-first.

In the book’s introduction, Peské and Marty recount an anecdote about how the accomplished playwright and opera librettist Francis de Croisset used to tear the covers off Fantômas crime novels to avoid embarrassment when reading such a low-brow stuff in public. But by mid-century, the authors asked, who remembers Francis de Croisset? Hardly anyone.[4] By contrast, they noted, readers continue to delight in the exploits of Arsène Lupin, Rouletabille, Chéri-Bibi, and Fantômas. While the celebrity of writers comes and goes, the popularity of these audacious avengers, detectives, and criminals remained.

“For the past half-century, these heroes, passed down from generation to generation, continue to exert a powerful influence and remain, whether we like it or not, part of the living literary landscape.” (Peské and Marty, 6)

Arsène Lupin, Rouletabille, Chéri-Bibi, and Fantômas each receive individual attention in subsequent blog entries. Although distinct characters, they share common features. Each is an “everyman,” emerging from obscure origins to become a social celebrity, criminal mastermind, or herculean man of action. None has a fixed identity, but assumes multiple aliases and disguises over the course of his adventures. All are ingenious, either through their intellectual prowess or ability to pull off spectacular ruses. They resist being split into opposing camps of good and evil, protagonist against antagonist, or detective versus criminal, and instead incorporate contrary impulses of anarchy, order, and an unbounded desire for liberation with tragic destiny into the fabric of their characters. In the end, the hero and antihero are one.[5]

Les souliers du mort (“The Dead Man’s Shoes”). Cover illustration by Gino Starace. Series “Fantômas,” no. 20. Collection “Le Livre populaire” (Paris: A. Fayard, 1912). Author’s collection.

NOTES

[1] Maurice Leblanc, “L’évasion d’Arsène Lupin,” Je sais tout, no. XII, January 15, 1905; English translation, “The Evasion of Arsène Lupin,” in Arsène Lupin, Gentleman-Thief, intro. Michael Sims (New York: Penguin Classics, 2007). All other translations from French are by the author.

[2] On Enrico Pranzini, see Aaron Freundschuh, The Courtesan and the Gigolo: The Murders in the Rue Montaigne and the Dark Side of Empire in Nineteenth-Century Paris (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017); on Meg Steinheil, see Sarah Horowitz, The Red Widow: The Scandal that Shook Paris and the Woman Behind It All (Naperville: Source Books, 2023); on Joseph Vacher, see Douglas Starr, The Killer of Little Shepherds: A True Crime Story and the Birth of Forensic Science (New York: Knopf, 2010); on the Bonnot gang, see John Merriman, The Ballad of the Anarchist Bandits: The Crime Spree that Gripped Belle Époque Paris (New York: Nation Books, 2017); and, on Madame Caillaux, see Edward Berenson, The Trial of Madame Caillaux (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992).

[3] The initial Nick Carter and Nat Pinkerton detective magazines were penned by “anonymous” authors John Russell Croyell, Thomas Harbough, and Frederick Van Rensselaer Dey and published in multiple European languages by Éditions Éichler in Dresden, London, and Paris. Parallel detective weeklies published in France at the time include: Marc Jordan, exploits surprenants du plus grand détective français (62 issues, 1907-1910), Lord Lister, le grand inconnu (30 issues, 1908), Miss Boston, la seule détective-femme du monde entier (20 issues, 1908-1909), Ethel King, le Nick Carter feminin (100 issues, 1912-1914), and Tip Walter, le prince des détectives (55 issues, 1912).

[4] Francis de Croisset (1877-1937) was the prolific playwright of more than fifty scripts and the opera librettist for Jules Massanet’s opera Chérubin (1905) and Reynaldo Hahn’s Ciboulette (1923). The humor in Peské and Marty’s anecdote stems from the fact that he and Maurice Leblanc co-scripted an Arsène Lupin play in 1912, subsequently adapted for film in 1916, 1917 and 1923, and as radio dramas on multiple occasions.

[5] As noted by philosopher Roger Caillois, “the effective crime and detective novel (roman policier) creates a powerful phantasmagoria of anarchy versus order, its revolutionary impulses equal to the power of conservatism and order to try to constrain it.” Paraphrased by Robin Walz in Pulp Surrealism: Insolent Popular Culture in Early Twentieth-Century Paris (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), p. 75.

SOURCES

Jacques Bisceglia, Trésors du roman policier, catalogue encyclopédique, 2nd éd. (Paris: Les éditions de l’amateur, 1986).

Élisabeth Parinet, Une histoire de l’édition à l’époque contemporaine, XIXe-XXe siècle (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2004).

Antoinette Peské and Pierre Marty, Les Terribles (Paris: Frédéric Chambriand, 1951).

Updated: October 27, 2025

Robin Walz © 2025

Leave a comment