Portrait of Émile Gaboriau, c. 1868. Unknown photographer; restoration by Jebulon. Gallica: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

One wintry February night in Paris, Sûreté Inspector Gévrol and his police squad responded to a reported disturbance in the slums of the 13th arrondissement. As they approached a squalid cabaret known as La Poivière (the “Pepper Pot”), they heard crashing sounds and raucous voices. Gévrol issued a curt “Open up! Police!” warning, and his men burst in. Tables and stools were overturned. Shards from plates, bottles, and glasses were strewn about. Old Mère Chupin, the proprietress, lay splayed out on a staircase, moaning. From an adjoining room, a bearded man armed with a dagger silently observed the policemen. Once discovered, he attempted to escape out the back, but was apprehended by an officer in the street who guarded the rear entrance.

Two bloodied men lay dead on the floor. A third, in death throes, declared he had gotten what he deserved before expiring. The captured man confessed he had killed all three men, but in self-defense. His claim was supported by Mère Chupin, who insisted the others had first assaulted him. Inspector Gévrol was having none of it. He immediately and intuitively deduced the four men were criminals in cahoots with one another and, in a deal turned sour, the one had killed the others. Despite the prisoner’s protestations of innocence, Gévrol was convinced the bearded man and Mère Chupin were accomplices, and they were hauled off to the police station at the Place d’Italie.

However, a young Sûreté Detective named Lecoq, also part the squad, wasn’t so sure this was an open and shut case. He thought the bearded man was not a common ruffian, but someone from a privileged background with a superior education pretending to be a lowlife, as betrayed by his fine manner of speech. Further, the armed man hung around after the police had entered La Poivière before attempting to flee the scene. He wanted to investigate further. Although Gérvol thought it a waste of time, he granted permission. For assistance, Lecoq chose a fifty-year-old rank-and-file policeman known as Père Absinthe, whose career had never amounted to much due to his fondness for alcohol and insobriety on the job.

Monsieur Lecoq by Émile Gaboriau (1869). Cover by Gino Starace. Collection “Le Livre Populaire” (Paris: Fayard, 1913). In Gino Starace, l’llustrateur de “Fantômas” (Amiens: Encrage, 1987). Author’s collection.

Lecoq postulated that the bearded man had not acted alone, but in concert with outside accomplices, a supposition reinforced by the discovery of muddy footprints in the snow behind the cabaret, which he and Père Absinthe made into plaster casts. Lecoq drew a map of the cabaret and serially labeled incidents from the crime, arrest, and follow-up investigation A to M. To make sense of it all, Lecoq sought out the advice of Père Tabaret, an amateur detective who had helped him on previous cases. Continuing to investigate for several weeks, Lecoq ascertained the murder culprit was a man named Mai.

After weeks of imprisonment, however, Inspector Gévol and his detectives were still unable to confirm the identity of the culprit as Mai. The prosecuting magistrate was stymied as well, failing to obtain a confession despite several rounds of interrogation. In a bold move, Lecoq convinced the prosecutor to release Mai, whom he believed would lead him to the murder accomplices. Upon release, Lecoq trailed Mai through the fashionable Saint-Germain-des-Prés neighborhood, when the suspect suddenly leaped over a wall and into the garden of the Hôtel de Sairmeuse. After gaining entrance to the aristocratic residence, however, Lecoq was unable to find any trace of Mai. In a subsequent conversation with Père Tabaret, the two conclude that Mai and the Duc de Sairmeuse are one and the same person. Lecoq declares, “If the true Mai is the Duc de Sairmeuse… I will have my revenge!”[1]

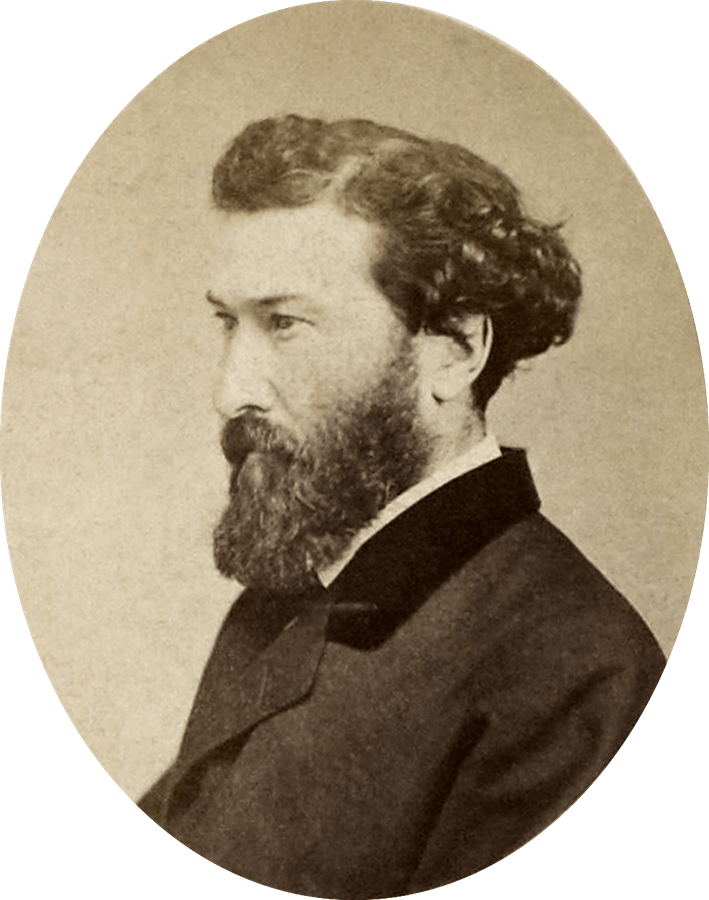

Émile Gaboriau, Carte de visite by Alphonse Liébert (1868). Collection: Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

Monsieur Lecoq (1869) was Émile Gaboriau’s final roman judiciaire (“judicial” or proto-procedural novel) that paired Sûreté Detective Lecoq and Père Tabaret. Like many of his popular novelist contemporaries, circuitous circumstances resulted in him becoming a writer. Étienne-Émile was born to Charles-Émile and Marguerite Gaboriau on November 9, 1832, in the town of Saujon along the Charante-Maritime Atlantic coast. His father was a postmaster assigned to various locations across France, including La Rochelle, Tarascon, and finally Saumur. Consequently, as a boy Émile received a scattershot primary education. For secondary school, his parents boarded him at the Jesuit Collège de Garçons in Cozes, near Saujon. As a collégien middle-schooler, Émile’s academic performance was unremarkable — “fair performance, mediocre work […] must redouble his efforts […] second level in mathematics, third in religious instruction” — with the notable exception of receiving a prize in Latin language and literature during his final year.[2]

Despite family efforts to shore up his education at the Collège Royale d’Angers, Émile never qualified to enter a baccalauréat degree program. He did, however, develop a passion for reading American and English fiction in French translation, particularly the adventure novels of James Fenimore Cooper, Ann Radcliffe’s gothic novels, and Edgar Allan Poe’s macabre short stories. Émile floundered for the next few years working as a notary clerk, enrolling in an dropping out of law school, and finally declaring himself without profession or residence. Enlisting in the French Army’s 5th Cavalry, he joined up with the 13th Hussards (mounted troops) in Algeria in 1851, returning to France five years later.

Failing to qualify for an army pension (which required eleven years of service) and cut off financially by his father, without resources Émile moved to Paris. Over the next three years, Gaboriau held a series of temporary positions as a secretary to an interrogating magistrate at the Palais de Justice, an assistant to an English toxicologist, and a carriage horse groomer. In 1858, he took a stab at journalism, covering society events and writing news blurbs for La Vérité and Le Tintamarre newspapers, as well as a securing a regular “Military Profiles” column in La Journal.

Soon, Gaboriau began to achive some success as a writer, publishing numerous short stories and essays. His literary career took off after becoming the personal secretary to popular novelist Paul Féval, who had launched a short-lived literary review, Jean Diable (1862-1863). Gaboriau’s first mystery novel, L’Affaire Lerouge (“The Widow Lerouge Case,” 1866) was published shortly after.

L’Affaire Lerouge by Émile Gaboriau (1866). Cover by Gino Starace. Collection “Le Livre Populaire” (Paris: Fayard, 1909). Wikimedia Commons: Public Domain.

The story opens with the murder of the Widow Lerouge, who lived in an isolated house on the margins of Bougival, a village along the Seine west of Paris. A young, Sûreté detective named Lecoq is assigned to the case, but he requests that Père Tabaret take the lead. Tabaret had worked as a pawnbroker and loan officer at the Mont-de-Piété bank, colloquially called as chez ma tante (“my aunt’s place”). Over the years, he became skilled at piecing together bits of information, exercising discretion, and divining the truth about what his déclassé bourgeois clients did and do not say when they needed quick cash. The Paris Police Prefecture, who solicited his services on occasion, nicknamed him Tireauclair (“Brings-to-light”) and continued to call upon him in retirement as an amateur detective.

Jean Béraud, Le Mont-de-Piété, ou chez ma tante, c. 1910. Wikimedia Commons: Public Domain.

In L’Affaire Lerouge, Tabaret proves that the murder suspect arrested by the Paris Police, the Vicount Albert de Commarin, secretly the Widow Lerouge’s bastard child, is innocent. The actual killer turns out to be a debauched and corrupt notary, Noël Gerdy, who had been serving as de Commarin’s defense counsel while imprisoned. The pieces of evidence that led Tabaret to conclude Gerdy was the murderer included a half-smoked cigar, a pair of elegant but muddy boots, and a commuter train timetable. L’Affaire Lerouge was a resounding commercial success as a feuilleton novel in Le Soleil newspaper in 1866 and issued as a book by publisher Édouard Dentu the same year.[3]

In Gaboriau’s subsequent mystery novels, Le Crime d’Orcival (1867), Le Dossier no. 113 (1867), and Monsieur Lecoq (1869), Sûreté Detective Lecoq takes the lead as the principal investigator. Like his mentor Père Tabaret, Lecoq shares the conceit of relying upon his own methodical examination of the evidence and reasoning rather than falling in line with standard Sûreté procedures.

Le Dossier no. 113 by Émile Gaboriau (1867). Cover by Gino Starace. Collection “Le Livre Populaire” (Paris: Fayard, 1913). Author’s collection.

After the Sûreté generale became an official branch of the Paris Prefecture of Police in 1853, Sûreté detectives worked directly for interrogating magistrates who issued arrest warrants and prepared cases against the accused. In the popular imagination, however, Sûreté agents continued to suffer from a reputation of being bellicose and overly familiar with criminal milieu, even occasionally recruited from their ranks. In sharp contrast, Gaboriau’s Lecoq is a dedicated, independent, and upright detective, the portrait of honesty within the much maligned Sûreté. His very name, Lecoq, invokes a noble and Gallic character (le coq or the rooster is one of the symbols of the French nation), setting him apart from and above the corrupt chef de la sûreté Vidocq and the criminal private detective Lecoq in Paul Féval’s Les Habits Noirs.

“I’m Monsieur Lecoq, the Cock! The Cock! ….. of novelists!” Caricature of Émile Gaboriau by A. Lemot in Le Monde pour rire satirical magazine, no. 12, May 23, 1868. Gallica: Bibliothèque nationale de Paris.

Gaboriau’s Monsieur Lecoq novels suffer, however, from plodding narratives and procedural drudgery. In Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes mystery, A Study in Scarlet (1887), the British sleuth mocked the French detective:

“Lecoq was a miserable bungler…. That book made me positively ill. The question was how to identify an unknown prisoner. I could have done it in twenty-four hours. Lecoq took six months or so. It might be made a text-book for detectives to teach them what to avoid.”[4]

From the perspective of the later “whodunnit” short stories and detective novels, Gaboriau’s romans judiciaires contain an overabundance of extraneous material, spread over hundreds of pages, that has little to do with solving the mystery.

This was not altogether Gaboriau’s fault, who wrote during the era of the great feuilletonistes of the Second Empire. The publishing demands of feuilleton novels, which required producing daily or weekly installments for periods of months or even years at a time, pulled his romans judiciaires in multiple directions. As the foundational scholar of French detective fiction Régis Messac observed, “Gaboriau’s novels are compromised by contradictory aesthetics: that of the short-story [mystery], which he got from Poe, and that of the feuilleton, which circumstances imposed upon him.”[5]

Gaboriau’s detective novels, Messac notes, were all written on a similar plan. The story opens with a crime, a murder or grand theft, enveloped in a mystery. Lecoq gathers evidence, conducts inquiries, and makes logical connections that lead him to the correct criminal suspect. Then, when the case is nearly solved, the story line is interrupted and the reader is transported back in time, as much as twenty years, to incorporate a labyrinthine romantic back story — a structure common to many late-nineteenth century French popular novels, which would combine two or three book-length volumes under one title. After lengthy detours, Gaboriau finally resolves the case: “Lecoq discovers secrets in six pages that had been absent from the previously recounted two hundred.”[6]

Title Page of Monsieur Lecoq, vol. 2 L’Honneur du nom, 6th edition (Paris: E. Dentu, 1873). Google Books: Biblioteca nazionale, Naples.

Accordingly, Monsieur Lecoq is divided into two volumes, L’Enquête (“The Investigation”) and L’Honneur du nom (“Honor Restored”). Only the first part is properly a detective story, as Lecoq conducts his investigation to discover the identity of the triple murderer in the seedy La Poivière cabaret. The bulk of L’Honneur du nom, by contrast, traces a long and torturous backstory about the fortunes and tribulations of the aristocratic Sairmeuse family. Towards the end of the book, Tabaret cautions Lecoq that, although Mai is actually the current Duc de Sarimeuse, the aristocratic family’s social and political clout renders them untouchable. When the murder case against Mai finally plays out in court, the judge dismisses it on the basis of insufficient evidence. Lecoq’s “revenge” is limited to the self-satisfaction of knowing that Mai and the Duc were indeed the same person.

Yet the demands of being a feuilletoniste only partially absolves Gaboriau. At bottom, Lecoq is neither a compelling character nor ingenious as a detective. The inferences he draws from evidence, Messac notes, are not all that remarkable. Matching footprints to shoes, noting that a burned cigar with no teeth marks or saliva on it was likely smoked in a holder, concluding that the hands of a clock have been tampered with if it reads 3:20 when the clock chimes eleven — such judgments do not require great leaps of logic.

Ultimately, Messac concludes, Gaboriau’s romans judiciaries more resemble the anecdotal and plodding Mémoires of former Sûreté Chief Canler, than the cerebral brilliance of an Auguste Dupin, Sherlock Holmes, Arsène Lupin, or Joseph Rouletabille. While Lecoq is young, handsome, energetic, and a dedicated police functionary, his dogged tenacity in “getting his man” falls flat in comparison to the thrills and rocambolesque antics readers relished in Paul Féval’s and Ponson du Terrail’s crime novels, concurrently published in the 1860s.

The initial failure of the law to apprehend an elusive criminal, or arrest the wrong person, is central to driving a detective’s inquiries in mystery novels. In the moral interpretation of the classic detective novel, the identification and punishment of the criminal acts as a kind of restoration of social order. By contrast, in Gaboriau’s romans judiciaires, as well as in the crime novels of his contemporaries, the back-and-forth between the intrepid detective and a criminal may or may not result in a legal conviction. In many French crime and detective novels in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, moral satisfaction and social restitution often took a back seat.[7]

At the conclusion of L’Affaire Lerouge, the fraudulent lawyer and murderer Noël Gerdy commits suicide with a pistol to evade arrest by the police banging at his door. By doing so, not only does he egotistically deprive the law its due course, he also safeguards the reputation of his fiancée and assures she will receive a secret stash of eighty-thousand francs. In the aftermath, Père Tabaret ponders:

After having believed in the infallibility of justice, he could no longer see anything but judicial errors.

The former adjunct police detective turned private investigator doubted the existence of crime, and came to believe that physical evidence proved nothing. He circulated a petition to abolish the death penalty and established an aid society on the behalf of poor and falsely accused suspects.[8]

Gaboriau understood that charging the police and the courts with the power to prosecute criminal offenders did not guarantee justice or moral restitution.

NOTES

[1] Émile Gaboriau, Monsieur Lecoq (Paris: Éditions Liana Levi, 1992), p. 225. All translations from the French are by the author.

[2] Bonniot, pp. 10-11.

[3] An shorter version of L’Affaire Lerouge was previously published as a feuilleton in Le Pay newspaper from September 14 to December 7, 1865, but was disparaged by reviewers as simply being “a pastiche of Murders in the Rue Morgue” (Bonniot, p. 112).

[4] Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet: The First Sherlock Holmes Mystery (New York: The Modern Library, 2003), p. 18.

[5] Régis Messac, Le “Detective Novel” et l’influence de la pensée scientifique (1929), updated edition (Paris: Encrage/Société des Belles Lettres, 2011), p. 432.

[6] Messac, p. 431.

[7] On the interpretation of the classic detective novel in terms of moral and social restoration, see Dennis Porter, The Pursuit of Crime: Art and Ideology in Detective Fiction (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981). The notion that criminals and detectives are pitted against one another in equal measure was first put forward by Roger Caillois in Le Roman policier (Buenos Aires: Éditions des lettres françaises, 1941).

[8] Gaboriau, L’Affaire Lerouge, p. 346.

SOURCES

Roger Bonniot, Émile Gaboriau, ou la naissance du roman policier (Paris: Éditions J. Vrin, 1985).

Dictionnaire des littératures policières, ed. Claude Mesplède, 2 vols. (Nantes: Joseph K., 2007).

Émile Gaboriau, L’Affaire Lerouge (Paris: Éditions Liana Levi, 1991).

_____. Monsieur Lecoq (Paris: Éditions Liana Levi, 1992).

_____. Monsieur Lecoq: The Classic Detective Novel, ed. E. F. Bleiler (New York: Dover, 1975).

_____. Monsieur Lecoq, adapted by Nina Cooper (Encino, Calif.: Black Coats Press, 2009).

Updated: August 8, 2025

Robin Walz © 2025

Leave a comment