Publicity Poster for the crime novel L’Amour à Paris by Mr. Goron, former Sûreté Chief, serialized in Le Journal (1889) and purportedly drawn from his Mémoires Inédites (“Unabridged Memoirs”). Illustrated by Paul Balluriau. Gallica: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

While Vidocq’s Mémoires laid foundations for the police memoir genre, he was not the first to write one. Over the course of the eighteenth century, Versailles Police Commissioner Pierre Narbonne kept a multi-year journal that included entries about his policing activities.[1] In the early nineteenth century, Joseph Fouché, Minster of Police under the Revolutionary Directory and Naopleon’s Consulate, published his two-volume Mémoires (1824). Vidocq’s innovation was to make the police memoir a form of popular reading. After the establishment of the Sûreté générale in 1854 — the French Sûreté police we associate with the likes of Chief Inspector Maigret, today the Police nationale — it became routine for former police chiefs and detectives to publish memoirs for celebrity and profit.

The first of these was former Sûreté chief Louis Canler, who became an inspector at Paris Police Prefecture in 1820 while Vidocq was still head of the brigade de sûreté. An upright police functionary, Canler disdained Vidocq’s “security squad,” composed of convicts and criminals, as illegitimate. Hitting his stride in the 1830s, Canler participated in making or witnessing dozens of arrests, including the Duchesse de Berry after leading a failed insurrection to reinstate the deposed Bourbon Monarchy, the pursuit and capture of “poet-assassin” Lacenaire, and the attempted regicide of French King Louis-Philippe by Corsican mass murderer Giuseppe Fieschi and accomplices.

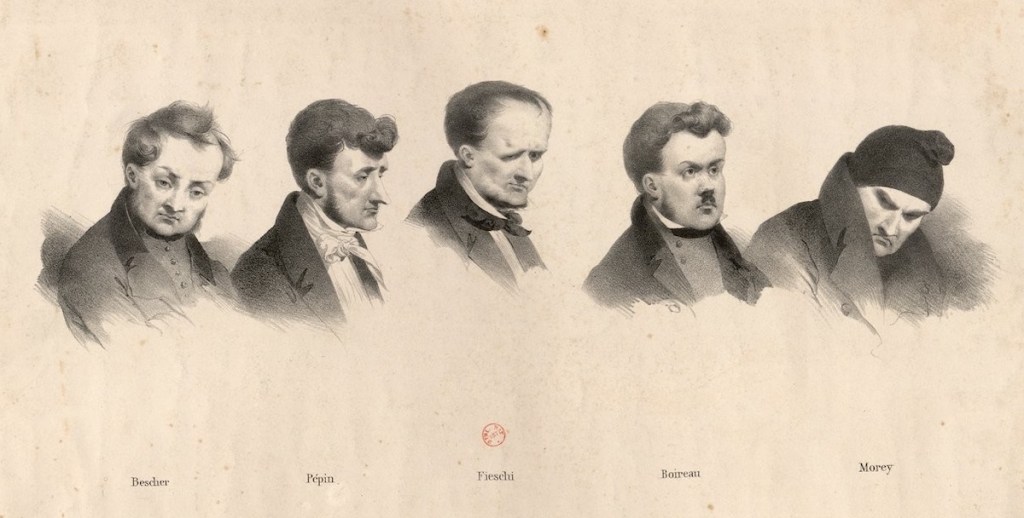

Engraved portraits of regicide conspirators Bescher, Pépin, Fieschi, Boireau, and Morey. Paris: Chez Gihault Frères, 1835. Gallica: Bibliothèqe nationale de France.

Following Canler’s arrest of socialist leader Louis Blanqui during the Revolution of 1848, Prefect of Police Pierre Carlier promoted him to lead the newly created Service de Sûreté. Now a police bureaucrat, Canler adopted the American practice of establishing files on all individuals upon arrest, which included notations about the suspect’s distinctive features to assist in the future identification of criminal recidivists. After the coup d’état of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte III in 1851, Canler was decommissioned due to his perceived political loyalty to previous regimes. He spent the next decade writing his memoirs, first published in 1862.[2]

Cover of Louis Canler, Mémoires de Canler, ancien chef du service de sûreté, compiled from the two-volume 1882 edition (Paris: Mercure de France, 1968). Author’s collection.

In the memoir’s preface, Canler provided three reasons why retired police agents write autobiographies: first, to seek celebrity based on an overinflated sense of self-importance; second, to exploit public curiosity through picaresque and bizarre stories; and third, to provide details about events in which one has personally participated. Even in this final case, Canler cautioned, discretion was needed to distinguish between those who write their memoirs to justify their checkered careers, and those who strive “to inculcate in young minds a noble repugnance for everything that is vile, despicable, and shameful” (Mémoires de Canler, p. 18).

Counting himself among the more high-minded police memoir writers, Canler attacked Vidocq’s Mémoires as belonging to the egotistical, exploitive, and dubious sort. In contrast to Vidocq’s embellishments and fabrications, Canler assured readers that this was a “setting the record straight” type of memoir. He apologized in advance for not being a “man of letters” and writing in an inelegant manner, but hoped nevertheless that readers would draw inspiration from them.

Canler’s Mémoires, however, did not sell well. The first edition in 1862 was severely abridged by Napoleon III’s censors. In 1882, publisher F. Roy released an augmented two-volume edition that restored the previously excised material, but it failed to generate significant sales. In 1888, Canler’s sister Adélaïde compiled a comprehensive manuscript of his memoirs, but she failed to secure a publisher.

For what the French reading public really wanted from police memoirs were not the facts (Canler’s biases still crept in), but sensational and heroic tales about the exploits of intrepid detectives who traversed the murky criminal underworld — which other authors and publishers were more than happy to provide. The first police memoir to achieve blockbuster success with a popular readership was the Mémoires de Monsieur Claude (1881-1883).

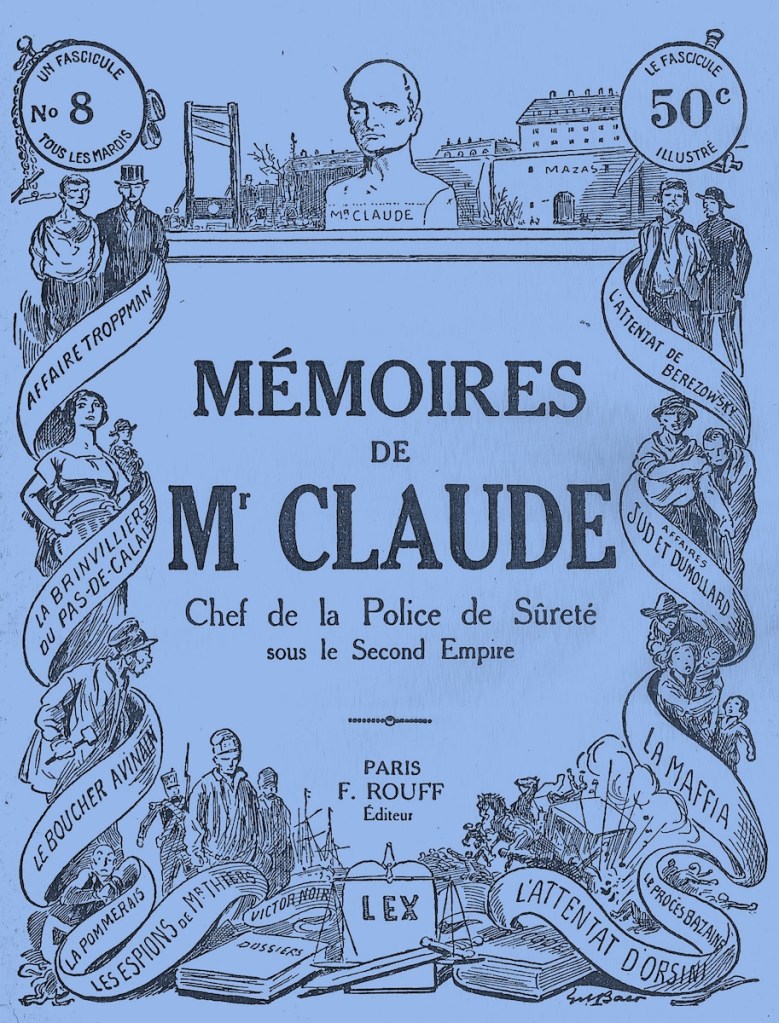

Title page of Mémoires de Monsieur Claude, Chef de la police de sûreté sous le second empire, 2 vols. (Paris: Jules Rouff, [1900]). Source: AbeBooks.

Antoine-François Claude was a court bailiff who became a police commissioner in 1836, and then worked his way up the bureaucratic hierarchy. In 1859 he was appointed Chef de la Sûreté générale, by which had only recently become an official branch of the Paris Police Prefecture. Upon retirement in 1875, Claude published articles in newspapers and magazines about sensational crimes that occurred during his tenure, most famously the killing spree by Jean-Baptiste Troppmann, who murdered the entire Kinck family in the Pantin suburb southeast of Paris in 1869.

“Crime in Pantin — Murder of the Kinck Family from Roubaix” (Detail). Épinal print, c. 1870. Wikimedia Commons: Criminocorpus.org.

Following Claude’s death in 1880, journalist and ghostwriter Théodore Labourieu anonymously penned the Mémoires de Monsieur Claude for publisher Jules Rouff, issued in ten volumes (1881-1883).[3] Labourieu embellished Claude’s career as chef de la sûreté, transforming him into a detective hero, whether the cases were real, apocryphal, or entirely fictional. In addition, Rouff was one of a new wave of entrepreneurial publishers in France who sought to make substantial profits through a combination of lowered prices and mass sales. In 1884, Rouff reissued Claude’s Mémoires in 103 serialized fascicules (small-format booklets), in 32-page chunks with uniform covers and engraved illustrations.

Mémoires de Mr. Claude, fascicule no. 8 (Paris: F. Rouff, 1884). Collection: Bibliothèque des littératures policières, Paris.

Released every Tuesday and priced at 50 centimes (roughly ten cents), nearly anyone could afford to buy an issue. A single story might be spread over several issues, so the final page of any fascicule could end abruptly, in mid-sentence even, and then pick up in the following installment. It is doubtful that many individuals subscribed to the entire series run, which totaled over 3,300 pages, but tens of thousands of readers could purchase at least a few issues, or even a few dozen, to the enormous profit of both ghostwriter Labourieu and publisher Rouff.

Not surprisingly, some former police chiefs and detectives profited financially more from publishing their memoirs than from the salaries they earned in what were often short stints at the Prefecture. One of these was the politically ambitious Louis Andrieux, the self-proclaimed “Deputy-Prefect of Police” who conducted a mop-up suppression of the Paris Communards after 1871. Appointed Paris Police Prefect in 1879, he was relentlessly attacked in the press, across the political spectrum, for excessive violence employed by his police agents. After only two years in office, Andrieux stepped down in 1881.

Caricature of Louis Andrieux by Coll-Toc (Alexandre Coilignon), in the satirical weekly Les Hommes d’Aujourd’hui, no. 272, 1886. The displayed proposal calls for taking out 900 million francs in loans to achieve budgetary savings. An absinthe spoon and empty glass rest on the podium. Wikimedia Commons: Private Collection (Public Domain).

Gustave Macé had a similarly brief career as a Sûreté Chief. Working as a police inspector since 1853, Police Prefect Andrieux appointed him to head the Service de Sûreté in 1879. After five short years in the position, Macé resigned, proclaiming that he was fed up with the Prefecture, ostensibly because it refused to implement “indispensable reforms” he had proposed. For its part, the Prefecture came down on Macé for administrative ineffectiveness, arbitrary arrests made by his agents, and his refusal to install a telephone in his office. As a consequence, Macé was forced into retirement in April 1884.

“M. Macé, Sûreté Police Chief.” Photo-engraved portrait (detail) in Le Voleur illustré weekly, March 27, 1884. Gallica: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

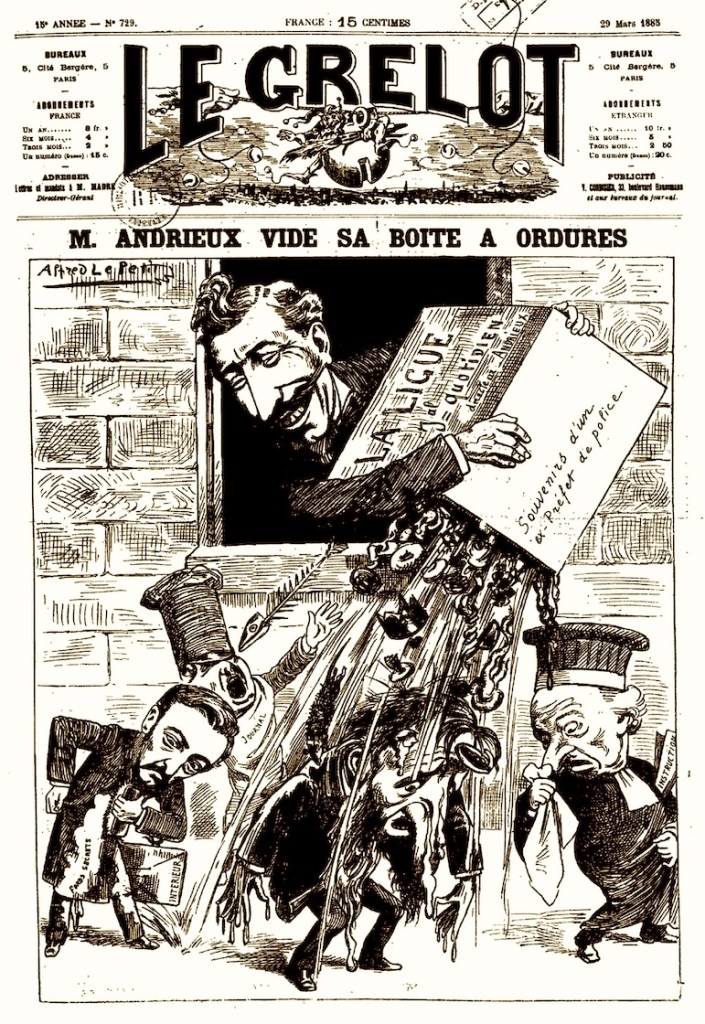

For both Andrieux and Macé, publishing memoirs brought them greater fortune and fame than their police careers. In 1885, publisher Jules Rouff issued Andrieux’s Souvenirs d’un préfet de police, which largely detailed internecine political squabbles within the Paris Prefecture.[4] In terms of his own career, Andrieux boasted about his surveillance of Radical politician Léon Gambetta and provided readers with insider information about gambling and prostitution rings in Paris. Not missing a commercial beat, publisher Rouff advertised the Mémoires de Mr. Claude in the front matter of Andrieux’s memoir.

“Monsieur Andrieux Empties His Trash Bin” upon political bureaucrats, journalists, and magistrates. Caricature by Alfred Le Petit in the satirical weekly Le Grelot, March 29, 1885. The side of the box reads, “Souvenirs of a Police Prefect.” Gallica: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Gustave Macé was more energetic as an author than he ever was as a policeman. He made his mark with the ten-volume “true crime” series, La Police Parisienne (“The Paris Police,” 1884-1904).[5] Published by Georges Charpentier, another upstart publisher who mass-marketed books cheaply at 3 francs 50 each, Macé promised insider revelations about the “most brutal and repugnant aspects of humanity” (Mon musée criminel, p. 11). His books were mishmash collection of crime stories, having little or nothing to do with his career. His sensationalized stories were peppered with argot and illustrated with photographic reproductions of criminal portraits, assault weapons, and burglary tools (some of which remain on display today in the Musée de la Préfecture de Police Museum in Paris).

Former Chef de la Sûreté François-Marie Goron followed suit. Born at midcentury in Rennes, trained as a pharmacist, and then commercially floundering for a decade as a wine merchant in Argentina, Goron returned to Paris and began his police career as an office secretary at the Prefecture in 1880. He worked his way up the functionary ladder to become a detective in 1885, Deputy-Chief of the Sûreté in 1886, and ultimately was promoted to Sûreté Chief at the end of 1887.

Portrait of François-Marie Goron. Uncredited engraving by Nicolas Stanislas Auguste Vimar in Figures contemporaines tirées de l’album Mariani, vol. 7 (Paris: Ernest Flammarion, 1902). Wikimedia Commons: Public Domain.

A decade later, Goron recounted his career in Les Mémoires de M. Goron, ancien chef de la Sûreté (1897).[6] As with other published police memoirs, the original four-volume edition of Goron’s Mémoires was reissued for a mass-reading audience in ten paperbacks priced at 30 centimes each, as well as in an even cheaper series of 253 eight-page fascicules sold at one sou each (five centimes, roughly a penny).

To bolster his reputation as a police detective, Goron drew upon renowned criminal causes célèbres and works of crime fiction to enhance his image. To add weight to anecdotes about pimps, conmen, and gangs (bandes noires) in the Parisian suburb of Pantin, for example, he summoned up the “sinister drama” of Troppmann’s mass murder of the Knick family in 1869 — although that occurred more than a decade before the beginning of his tenure at the Sûreté.

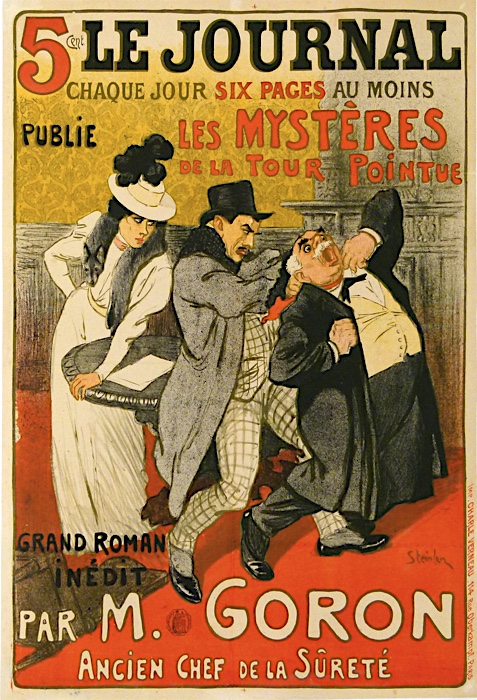

Goron’s most famous case was the Pranzini Affair, the murder of Parisian demimonde courtesan Marie Regnault by Enrico Pranzini in 1887.[7] The lead investigator in the case, Goron couldn’t resist comparing himself to popular novelist Émile Gaboriau and his fictional detectives Père Tabaret and Monsieur Lecoq. He also placed the Mémoires alongside criminal underworld novel series such as Honoré de Balzac’s Splendeurs et misères de courtisanes, Ponson du Terrail’s Rocambole, and Paul Féval’s Les Habits noirs. Goron even tried his hand at writing crime fiction, amplifying his novel titles with the authorial byline, Ancien Chef de la Sûreté (“Former Sûreté Police Chief”).

Publicity poster for Goron’s crime novel, Les Mystères de la Tour Pointue (“The Pointue Tower Mysteries”), serialized in the daily newspaper Le Journal (1899). Illustrated by Théophile Alexandre Steinlen. Wikimedia Commons: Public Domain.

However, Goron’s greatest fame and fortune did not come from publishing his Mémoires or crime fiction, but by becoming a private investigator. In the footsteps of Vidocq’s Renseignements Universels (“General Information Office”), by the mid-nineteenth century a number of private police agencies were operating in Paris.[8] In 1903, Goron opened Détective Office, offering private consultations and inquiries in strictest confidentially for a paying clientele. Gorgon’s celebrity as a private investigator was soon surpassed, however, by an even more energetic private detective, Eugène Villiod (to be continued…).

NOTES

[1] Pierre Narbonne’s entries are compiled in Journal de Police, 2 vols. 1701-1733 and 1734-1746 (Clermont-Ferrand: Editions Paleo, 2002); and, Joseph Fouché, Mémoires de Joseph Fouché, duc d’Otrante, ministre de la police générale, 2 vols. (Paris: Le Rouge Librairie, 1824).

[2] Louis Canler, Mémoires de Canler, ancien chef du service de sûreté (1862; revised edition in 2 vols., 1882), ed. Jacques Brenner, series “le Temps retrouvé” (Paris: Mercure de France, 1968). Throughout this blog entry, English translations from the French are by the author.

[3] Mémoires de Monsieur Claude, Chef de la Police de Sûreté sous le Second Empire, 10 vols. (Paris: Jules Rouff, Éditeur, 1881-1883). Reissue: Mémoires de Mr. Claude, in 103 fascicules (Paris: F. Rouff, [1884-1885]).

[4] Louis Andrieux, Souvenirs d’un préfet de police, 2 vols. (Paris: Jules Rouffe et Cie, Éditeurs, 1885).

[5] The titles in Gustave Macé’s series, “La Police parisienne” (Paris: Charpentier): Le service de la Sûreté (1884), Mon premier crime (1885), Un joli monde (1997), Gibier de Saint-Lazare (1888), Mes lundis en prison (1889), Mon musée criminel (1890), Crimes impunis (1897), Aventuriers de genie (1902), and Femmes criminelles (1904).

[6] Les Mémoires de M. Goron, ancien chef de la Sûreté, 4 vols. (Paris: Ernest Flammarion Éditeur, 1897). Reissue: Les Mémoires de M. Goron, ancien chef de la Sûreté, in 10 volumes and 253 fascicule booklets (Paris: J. Rouff et Cie, 1900).

[7] For a riveting account of the Pranzini Affair, see Aaron Freundschuh, The Courtesan and the Gigolo: The Murders in the Rue Montaigne and the Dark Side of Empire in Nineteenth-Century Paris (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017).

[8] Private investigation agencies in mid-nineteenth-century Paris included: L’Agence universelle Gorgeon et Cie (1848), Cabinet Mazier (1851), and L’Agence commercial et industrielle du magistrate Geyrard-Baux (1860).

SOURCES

Histoire et dictionnaire de la Police: Du Moyen Âge à nos jours, ed. Michel Aubouin, Arnaud Teyssier and Jean Tulard, collection “Bouquins” (Paris: Robert Laffont, 2005).

Dominique Kalifa, Histoire des détectives privés en France (1832-1942), 2nd ed. (Paris : Nouveau Monde éditions, 2007).

Élisabeth Parinet, Une histoire de l’édition à l’époque contemporaine, XIXe-XXe siècle (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2004).

Updated: May 17, 2025

Robin Walz © 2025

Leave a comment