“The Vicount Ponson du Terrail” by André Gill. La Lune, February 24, 1867. Wikimedia Commons: Universitätsbibliothek, Heidelberg.

Q: Who or what is Rocambole?

A: Rocambole is the son of Ponson du Terrail, who created and gave birth to Rocambole.

Q: Why did Ponson du Terrail create and give birth to Rocambole?

A: Ponson du Terrail created and gave birth to Rocambole to terrorize the dreams of readers, stupefy the population with shock treatment, and render literary connoisseurs idiots.

Q: Will Rocambole have an end?

A: No, Rocambole will never come to an end.

Q: Why won’t Rocambole ever come to an end?

A: Rocambole will never come to an end, because Ponson du Terrail doesn’t want to bother with the dolts who can’t live without Rocambole.[1]

Ponson du Terrail’s Rocambole signals the transition in mid-nineteenth-century France from literary installment novels (feuilletons), pioneered by the likes of Honoré de Balzac and Eugène Sue, to the commercial production of popular novels as “industrial literature.” The shift was fueled by a collaboration between newspaper publishers and round-the-clock writers who were paid by the line. The goal was to crank out as many words as possible on a daily basis to yield thick-as-a-brick yarns, issued in daily installments for a rapidly growing mass market of readers.

The timing of Ponson’s Les Drames de Paris (1857-1862) was fortuitous. Napoleon III’s Second French Empire was marked by political and cultural repression in terms of decreased individual liberties and increased censorship of the press. Some of France’s most popular authors, including Eugène Sue, Alexandre Dumas, and Victor Hugo, had gone into exile. Sue’s current feuilleton novel, Les Mystères du people (“Mysteries of the People”), was officially suspended in 1857 for reasons of “inciting hatred and disrespect against the government.”[2] The same year, Gustave Flaubert and Charles Baudelaire were each put on trial on charges of “offense to public and religious morality” for Madame Bovary and Les Fleurs du mal, respectively.

Concurrently, feuilleton novels published in newspapers were rapidly becoming a common denominator of cultural literacy. A mass readership for popular novels took off when newspapers began to publish novels in daily installments along the horizontal rez-de-chaussée (“ground floor”) at the bottom of the front page. In 1863, Le Petit Journal embarked upon a two-pronged marketing strategy of featuring a feuilleton installment in each issue and dropping the daily price of the newspaper to one sou (a five centime coin, roughly a penny). Within two years, Le Petit Journal sold over 250,000 issues a day. For the price of a baguette, nearly anyone could afford to buy an entire week’s worth of the newspaper and follow its feuilleton novel.

The commercial benefits for publishers, writers, and readers were multiple and reciprocal. Publishers realized that the celebrity of popular authors could boost newspaper sales, and they launched publicity campaigns to promote new feuilleton novels. In turn, successful writers could negotiate their by-the-line salaries, which ranged anywhere from five centimes to one franc per line. The number of installments in a novel varied in length, from several hundred to thousands of lines, sometimes assisted by teams of uncredited ghostwriters to write under the contracted author’s signature.

Photographic Portrait of Ponson du Terrail by André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, c. 1860. Collection: Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

While biography is a suspect key to literary interpretation, there are sympathies between Ponson’s life and his rocambolesque works.[1] Pierre Alexis Ferdinand Joseph de Ponson was born on July 8, 1829, into a family of upstart aristocrats. The paternal side of the family bore military credentials, but Pierre Alexis identified with his maternal lineage, which claimed ancestral ties to the legendary sixteenth-century knight Pierre Terrail, Lord of Bayard.

Pretensions to aristocratic grandeur hit a wall of reality, however, when he was refused admission to the Naval Academy of Marseille due to insufficient proof of his family pedigree. So at age eighteen, Pierre Alexis abruptly changed his life direction and headed to Paris to become a writer. Arriving in the capital during the revolutionary days of June 1848, he was immediately conscripted into the National Guard and promoted to officer’s rank for his part in the suppression of the radical uprising.

With the cessation of hostilities, in 1849 publisher Alfred Nettement commissioned Ponson to write a serialized story for his royalist newspaper L’Opinion Publique, which advocated a latter-day restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. He obliged with La Vraie Icarie (“True Icaria,” 1849), a politically reactionary rejoinder to Etienne Cabet’s socialist utopian novel, Voyage en Icarie (“Voyage to Icarus Island,” 1840). Soon after, Le Journal des Faits published Ponson’s first major feuilleton, Les Coulisses du monde (literally “The Stage-Wings of High Society,” but figuratively “The Secret Lives of the Rich and Famous”) in 95 installments, 1851-1852. From there, his career as a feuilletoniste took off.

Ponson’s novels were composed through a pastiche of repetition and hyperbole. He did not plot out and craft his feuilletons so much as he rapidly copied and pasted them together by lifting his content from other works of fiction and sensationalist newspaper reportage. According to media sociologist, Gabriel Thoveron:

He didn’t invent anything; he copied. He copied everything, sentimental novels, horror novels, historical novels (they called him the “Alexandre Dumas of the Batignolles”), the Mystères de Paris, and more. He borrowed from everywhere and could write as many as five novels at the same time, keeping track of each. Imagine the sources it took to keep that level of production afloat! He knocked off 10,000 pages a year, for twenty years. Editing his “complete works” is inconceivable. His feuilletons were written from one day to the next, without a plan, and sometimes without coherence….[3]

Mass readership influenced Ponson’s writing as well. According to literary critic François Caradec, “The pastiche-author is not alone; the complicity of his readers is required in order to be believed.”[3] Hastily constructed and voluminous, Ponson’s serials were padded with extraneous filler, and it became the task of the reader to unearth gems among the stones. His success was not based on the veracity of his novels or their literary merits, but upon reader enjoyment of the pastiche, combining familiar elements and plot expectations with novelty and surprise swerves in the story.

When Ponson gave up Les Drames de Paris in 1862, it was not because Rocambole had become unpopular; he simply wanted to launch additional feuilleton novel series. He brought the character back in 1865 with La Résurrection de Rocambole (“The Resurrection of Rocambole”), serialized in Le Petit Journal and launched with a massive advertising and poster campaign.

Le Résurrection de Rocambole, Collection “Livre Populaire” (Paris : Arthème Fayard, 1909). Cover by Gino Starace. Author’s collection.

In this new set of adventures, Ponson transformed Rocambole from a malevolent criminal into a justicier, an avenger hero. After five years of hard labor as “Prisoner 117” in Toulon prison (rather than Cadiz, as in the previous episode), a reformed Rocambole has become a champion of the falsely convicted. He is also fair, blonde, and handsome once more, a physical ennoblement to match his moral redemption.

Two new confederates join Rocambole: Milon, a good-hearted though dull-witted ex-convict pal, and Vanda, a scorned Russian princess with a ferocious avenging spirit. The Countess Artoff returns to assist him as well. The trio are fiercely loyal to Rocambole, whom they obey as le Maître (“the Master”). Rocambole the avenger proved to be wildly popular with the reading public, attracting 50,000 new readers to Le Petit Journal.

The plot of La Résurrection de Rocambole revolves around the kidnapping of Antoinette and Madeleine, two wealthy and orphaned sisters, by the evil Barons Karle and Philippe de Morlux, who want to steal their inheritance. Antoinette’s story plays out in Paris, where a corrupt private detective named Timoléon assists the Morlux brothers. The plot against Madeleine occurs in Russia, back and forth between Moscow and St Petersburg, where a treacherous Russian Countess named Vasilika directs crimes masterminded by the nefarious Barons. Adopting the alias Major Avatar, Rocambole and his companions pursue the criminals, foil their schemes, and save the sisters.

In the novel’s cliffhanger ending, Countess Vasilika mortally wounds Rocambole during a duel by thrusting a sword into his chest, up to the hilt. At that moment, Vanda bursts upon the room, draws a pistol, and blows Vasilika’s brains out. With blood gushing from his chest, Rocambole takes flight. Milon and Vanda follow his trail of blood to a riverbank:

“Ah!” Milon cried out. “Once more, he is dead!”

But Vanda straightened herself up, seething, furious, fire in her eyes.

“No!” she said. “No, it’s not possible, no, God doesn’t want it… No, ROCAMBOLE IS NOT DEAD!”

La Résurrection de Rocambole, p. 748.

Indeed, the criminal-turned-avenger was not dead. In 1866, La Petite Presse published Le Dernier mot de Rocambole (“The Final Word on Rocambole”) to even greater commercial success, acquiring an additional 100,000 readers for the newspaper. The newspaper carried Ponson’s subsequent Rocambole adventures as well, Les Misères de Londres (“The Miseries of London,” 1868) and Les Démolitions de Paris (“The Rubble of Paris,” 1869).

Le Dernier mot de Rocambole, Collection “Livre Populaire” (Paris : Arthème Fayard, 1909). Cover by Gino Starace. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Plots were as convoluted as ever: a gang of stranglers from India terrorizes Paris and London, a villainous English Lady falls in love with Rocambole, a fortune is restored to a disinherited Irish Lord. Rocambole assumes multiple and unlikely aliases: a Scotland Yard detective, a German doctor, an English psychiatric alienist, a Scottish evangelist, a prison executioner, a sixteen-year-old peasant lad, an eccentric English Lord who keeps a scrapbook of “curious crimes,” and others.[5] The rocambolesque series only came to an end with the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, and Ponson’s coincidental and premature death by smallpox in January 1871.

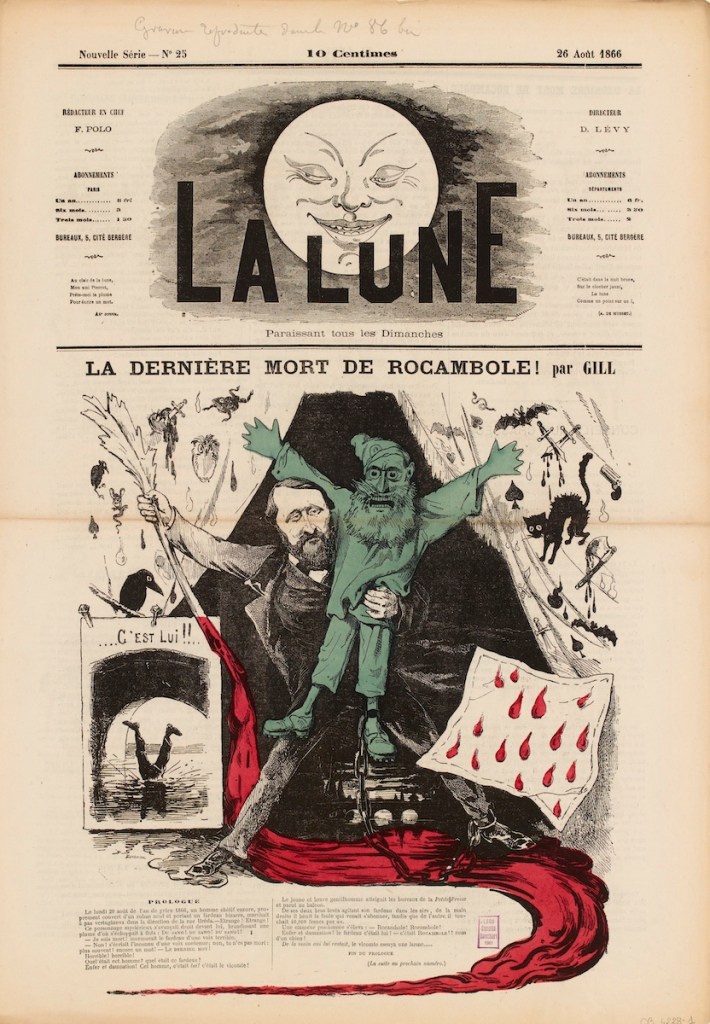

“The Final Death of Rocambole!” by André Gill. La Lune, August 26, 1866. Collection: Musée Carnavalet, Paris. A pun in French: le dernier mot (“the final word”) becomes la dernière mort (“the final death”).

Despite Ponson’s success, or perhaps due to it, his novels were savaged by the critics. More than any other popular series of the era, Rocambole represented what the nineteenth-century literary critic Sainte-Beuve decried as “industrial literature.” As characterized by Pierre Larousse in the Grand Dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle (“Universal Encyclopedic Dictionary of the 19th Century”): “His work is based on a series of extraordinarily improbable adventures, and the vulgarity of its characters, mostly populated with hardened criminal types, is nauseating.” [6]

The entry on “Vicomte Ponson du Terrail” in Abbot Louis Bethléem’s Romans à lire et romans à proscrire (“Novels to Read, Novels to Ban”) reads:

Adventure novelist with an extraordinary imagination. He published dismal and unbelievable novels full of impossible plots in newspaper installments. In them, one could find phrases such as, “This man’s hand was as cold as a snake’s.” His Rocambole, published in several parts, profited from an enormous wave of popularity. It is, in fact, deleterious.[7]

Gustave Flaubert lampooned Ponson in a fragment from L’Album de la marquise (1868):

The year was Eighteen-fifty-something. October was coming to an end. An Amazon mounted on a handsome black horse of the Irish race galloped along the sheer route of Elberstein manor.

This Amazon was the Marquise.

Some distance behind her, driving an elegant Ehrler carriage harnessed to a magnificent horse, followed a thoroughly young man with extremely fine manners.

This man was the Viscount…

“Oh!” He said, lighting his cigar with lightning flashing from his eyes… “Let me kiss your forehead, even if it means taking a bullet to my chest.”[8]

The general consensus among the literary establishment was that Ponson was a hack writer who played to the basest desires of his readers.

“Authentic Portrait of Rocambole” by André Gill. La Lune, November 17, 1867. Collection: Musée Carnavalet, Paris. The caricature unites Rocambole (left) with Emperor Napoleon III (right).

Yet as far as Ponson was concerned, literary style was beside the point. The public loved Rocambole, he earned a lucrative income, and that sufficed. Émile Gaboriau, author of the Père Tabaret and Monsieur Lecoq detective novels, concurrently published in the 1860s, expressed admiration for Ponson’s success in attracting readers:

Every evening, one of my friends rushes out to get the newspaper that carries the exploits of Rocambole. “God!’” he exclaims. “How Ponson gets on my nerves! He invents the most absurd stories, and he doesn’t even know how to write proper French!” But the following day, he buys the next installment.[9]

As a writer of detective novels, Gaboriau well understood that la suite au prochain numéro (“to be continued in the next issue”) fed the commercial dynamism that nourished newspaper sales, writers’ incomes, and readers’ pleasures. Without a doubt, Ponson du Terrail was a popular novel trailblazer.

NOTES

[1] A. H., Le Bonnet de coton (1867, a satirical weekly newspaper), quoted in Jean-Luc Buard, “Les Infortunes critiques d’un Romancier, ou Charges, parodies et caricatures littéraires du Ponson du Terrail (1858-1863),” Le Rocambole 2 (Fall 1997): 23. All English translations throughout this post by the author.

[2] Élisabeth Parinet, Une histoire de l’édition à l’époque contemporaine XIXe-XXe siècle (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2004), p. 288. The following quotation is from this reference as well.

[3] Gabriel Thoveron, Deux Siècles de Paralittératures: Lecture, Sociologie, Histoire (Liège: Editions du CÉFAL, 1996), p. 168. In fact, an exhaustive annotated bibliography of Ponson’s works has been compiled by Alfu (pseudo. Alain Fuzellier) in Ponson du Terrail: Dictionnaire des œuvres (Amiens: Encrage, 2008).

[5] Quoted in Charles Grivel, “Le retournement parodique des discours à leurres constants,” in Dire la parodie: Colloque de Cerisy, ed. Clive Thomson and Alain Pagès (New York: Peter Lang, 1989), p. 29.

[6] A complete listing of the aliases of Rocambole is presented in Didier Blonde, Les Voleurs de visages: Sur quelques cas troublants de changements d’identité : Rocambole, Arsène Lupin, Fantômas, & Cie (Paris: Métailié, 1992), 136-8.

[7] “PONSON DU TERRAIL,” in “Documents” [Facsimiles], Ponson du Terrail, Dossier 1, ed. René Guise (Nancy: Centre de Recherches sur le Roman populaire, 1986), D3.

[8] “Vicomte Ponson du Terrail,” Abbé Louis Bethléem, Romans à lire et romans à proscrire, in “Documents,” D4.

[9] Gustave Flaubert, L’album de la marquise,” in “Annexes,” La Résurrection de Rocambole, p. 787.

[10] Émile Gaboriau, Le Pays (July 17, 1866), in “Annexes,” La Résurrection de Rocambole, p. 778.

SOURCES

M. L. Chabot, Rocambole: Un roman feuilleton sous le Second Empire (Paris: Société des Gens de Lettres, 1995).

Matthieu Letourneux, Fictions à la chaine: Littératures sérielles et culture médiatique (Paris: Seuil, 2017),

Henri-Jean Martin and Roger Chartier, eds., L’Histoire de l’édition française, vol. III Les Temps des éditeurs: Du Romantisme à la Belle Époque (Paris: Promodis, 1985).

Pierre-Alexis Ponson du Terrail, La Résurrection de Rocambole, Collection “Bouquins” (Paris : Robert Laffont, 1992).

Klaus-Peter Walter, “La carrière de Ponson du Terrail,” Le Rocambole 9 (1999): 13-48.

Updated: June 14, 2025

Robin Walz © 2025

Leave a comment