Ponson du Terrail, Les Drames de Paris: Rocambole, reissued in 157 weekly installments (Paris: Jules Rouff, 1883-1886). Cover by Kauffmann. Collection: Bibliothèque des Littératures Policières, Paris.

Pierre Alexis Ponson du Terrail (1829-1871) was the most prolific and commercially successful popular novelist of nineteenth-century France. His enduring character is Rocambole, a criminal-turned-avenger hero whose exploits were serialized in daily newspapers, 1857-1870.[1] Aside from aficionados of nineteenth-century popular fiction, hardly anyone reads Ponson’s Rocambole series today. Yet the adjective rocambolesque, meaning “fantastic, incredible, resembling by its astonishing improbabilities the adventures of Rocambole,” has imprinted his cultural legacy in French collective memory.[2]

The year 1857 marks the ascendancy of Ponson’s popularity as a novelist with the serialization of Les Drames de Paris (“The Tragedies of Paris”) in the daily newspaper La Patrie. A decade later, Ponson recounted how Rocambole became the hero of the series in “La Vérité sur Rocambole” (“The Truth about Rocambole,” 1867). In this highly embellished autobiographical sketch, Ponson recalls first meeting Rocambole, formerly the leader of a criminal band called Les Valets de Cœurs (“The Jacks of Hearts”), in the fall of 1857, and novels about his adventures developed from there. The story was an invented memory, as no character named Rocambole even appeared in Les Drames de Paris until the series was already several months under way.

Ponson called the series Les Drames de Paris to capitalize upon Eugène Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris. He was not alone in using the “something of Paris” title to cash in on Sue’s success, as many popular novelists recycled the title formula for decades.[3] The plot of the first novel in the series, L’Héritage mystèrieux (“The Mysterious Inheritance”), revolves around the restoration of a lost familial inheritance and the defeat of the criminal antagonists who are after it. From the get-go, Les Drames de Paris took on a rocambolesque life of its own.

“Prologue: The Two Brothers,” Andrea de Felipone (left) & Armand de Kergaz (right), in Ponson du Terrail, Les Drames de Paris (Paris: Charlieu et Huillery, 1865). Engraved illustration by Auguste Belin. Source: LastDodo (Catalog for Collectors).

The prologue to L’Héritage mystérieux opens with Colonel Armand de Kergaz, Captain Paolo de Felipone, and a cavalryman named Bastien suffering through the bitter winter retreat of Napoleon’s Grand Army from Moscow in 1812. The aristocratic Kergaz is “a real man and noble figure,” whose blue eyes convey courage and loyalty (L’Héritage mystérieux, vol. 1, p. 2). By contrast, the Italian Captain Felipone, “possessing all the vices of degenerate peoples,” is a soldier of fortune (p. 9).

Believing he will not survive the frozen march home, Colonel de Kergaz writes out his last will and testament, leaving half of his inheritance to Felipone on the condition the Italian Captain marry his widow. Once in possession of the document, Felipone dispatches both Kergaz and Bastien with shots from his pistol. The double-crosser then sets off for Brittany to claim his ill-gained fortune.

Three years later, Felipone marries the Countess de Kergaz. To secure sole possession of the Kergaz estate, Felipone tosses the Countess’s son, named Armand after his father, into the sea. Bastien, who has survived Felipone’s gunshot, miraculously appears on the scene and rushes to the side of the Countess, in the throes of childbirth. Bastien recounts how the nefarious Felipone betrayed and killed her first husband. Upon hearing the shocking news, the Countess dies — but not before delivering a second son, Andréa de Felipone.

Jumping ahead to 1840, Armand, who survived the drowning attempt, is an art student in Rome. Learning of his stepfather’s treachery, and that his Andréa will inherit the family fortune, Armand returns to Paris. The half-brothers confront each other at a masked ball in Montmartre and prepare to duel. Suddenly, Bastien interrupts the combatants and escorts them to the deathbed of the Count de Felipone. Filled with remorse in his dying moments, Felipone tells Andréa that Armand is the true inheritor of the Kergaz fortune. Refusing to accept this, Andréa declares:

“So, virtuous brother, it’s between the two of us! We’ll see who carries the day, the philanthropist or the bandit, hell or heaven… Paris will be our battlefield!” (Rocambole: L’Héritage mystérieux, vol. 1, p. 66).

Some time later, a figure from London’s criminal underworld, the Irish Baron Sir Williams (an alias of Andréa), appears in Paris. Assisted by a seductive and conniving courtesan named Baccarat, le génie du Mal (“the Evil Mastermind”) Sir Williams seeks to destroy the lives of Armand and his friends.

Ponson du Terrail, Les Drames de Paris: Rocambole, Series “Le Livre Populaire” (Paris: Arthème Fayard, 1909). Cover by Gino Starace. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

No character named Rocambole had yet appeared in Pondon’s meandering feuilleton novel. Toward the end of L’Héritage mystèrieux, the story shifts to the village of Bougival, west of Paris, where a bitter old hag named Maman Fripart runs a low-life bar. One of her gofers is a “malicious and insolent” twelve-year old-orphan, whom she had adopted and nicknamed “Rocambole” (L’Héritage mystérieux, vol. 2, p. 176).

At this point, Rocambole was less a character than a set of inherited characteristics. The etymology of the name comes from the German Rockenbolle, a variety of garlic with an especially large bulb and a spicy-yet-sweet flavor. In the eighteenth century, the French noun rocambole meant “anything with a spicy attraction.”[4] During the French Revolution, La Rocambole des journaux was a satirical political handbill that lampooned the revolution’s principles and leaders. Insolent, malicious, and piquant were linguistic attributes that predated Ponson’s character.

That Rocambole emerged as a principal character in Les Drames de Paris can be attributed to Ponson’s willingness to bend to the commercial demands of writing novel installments on a daily basis for a newspaper with a large circulation. The feuilletoniste writer does not know in advance which characters, episodes, or plotline twists will prove popular with readers. As the literary historian of popular novels Régis Messac noted:

“The feuilleton novel is a fishing line with multiple hooks, one for each day. This is how the process ‘la suite au prochain numéro’ (‘to be continued in the next issue’) works” (Messac, p. 388).

Neither writers, whose salaries are paid by the line, nor newspaper publishers, whose profits depend upon sales, care which hooks catch their readers. Their primary concern is that readers return to purchase tomorrow’s installment. The incidental character of Rocambole was one of the hooks that proved commercially successful for Ponson and La Patrie.

At Maman Fripart’s Inn, Sir Williams’s second-in-command is shot and killed in a tussle with Armand de Kergaz. In immediate need of another character to fill the role, Ponson turned to Rocambole. Inexplicably, he transformed the orphaned child into a swashbuckling sixteen-year-old rogue, “an accomplished horseback rider within a week, swordsman by instinct, crack shot with rifle and pistol, swimmer like a fish to water” (L’Héritage mystérieux, vol. 2, p. 256). A few chapters later, Rocambole is fully grown, dashing, and audacious, and he becomes Sir Williams’s new right-hand man. Yet the nefarious duo is unsuccessful. At the conclusion of L’Héritage mystèrieux, Armand emerges victorious, the courtesan Baccarat repents and enters a convent, and Sir Williams slinks away.

Ponson du Terrail, Le Club de Valets de Cœurs, Series “Le Livre Populaire” (Paris: Arthème Fayard, 1909). Cover by Gino Starace. Author’s Collection.

Ponson continued the series with Le Club des Valets de Cœurs. Believing his half-brother has repented, Armand de Kergaz pardons Andréa and assigns him to head a private police force to defeat a secret band of criminals, the “The Jacks of Hearts Club.” The leader of the gang, however, is none other than Sir Williams (that is, Andréa). In a move to continually innovate the series, Ponson reduces Sir Williams’s role to a behind-the-scenes mastermind, and brings Rocambole, alias the Vicount de Cambolh, a handsome and blonde Swedish aristocrat, to the fore as the active antagonist. Despite Rocambole’s dutiful execution of his assigned criminal tasks, once again Sir Williams’s schemes are foiled.

In the continuation of the series, La Revanche de Baccarat (“Baccarat’s Revenge”), Rocambole is seriously wounded during a sword fight with Armand. Believing he is dying, Rocambole reveals to Armand that his half-brother Andréa is the leader of the Jack of Hearts gang. After Rocambole recovers from his wounds, Armand pardons and compensates him for his injury to the tune of 200,000 francs. The sly rogue then flees to England.

Enter the Countess Artoff, who is no longer the conniving prostitute Baccarat, but has been reborn as a noble avenger. Intervening on behalf of Armand, Artoff captures Sir Williams and assembles a tribunal of his former victims to punish him. To assure that no one will ever again fall prey to his hypnotic magnetism or evil eloquence, the Countess orders her minions to gouge out Sir Williams’s eyes, slice off his tongue, and slash his face. Disgraced and disfigured, Sir Williams is banished to Brazil to live among savages.

Up to this point, the series operated according to melodramatic oppositions of le Bien contre le Mal (“Good versus Evil”), but being on the side of goodness did not guarantee victory. Armand, ostensibly the hero, is easily duped. The vengeance of the Countess Artoff is elevated above the law. And the criminal Rocambole is rewarded for having opportunistically played all sides for personal gain. Reader demand for even more rocambolesque stories meant that Ponson would continue to bring astonishing changes to the series.

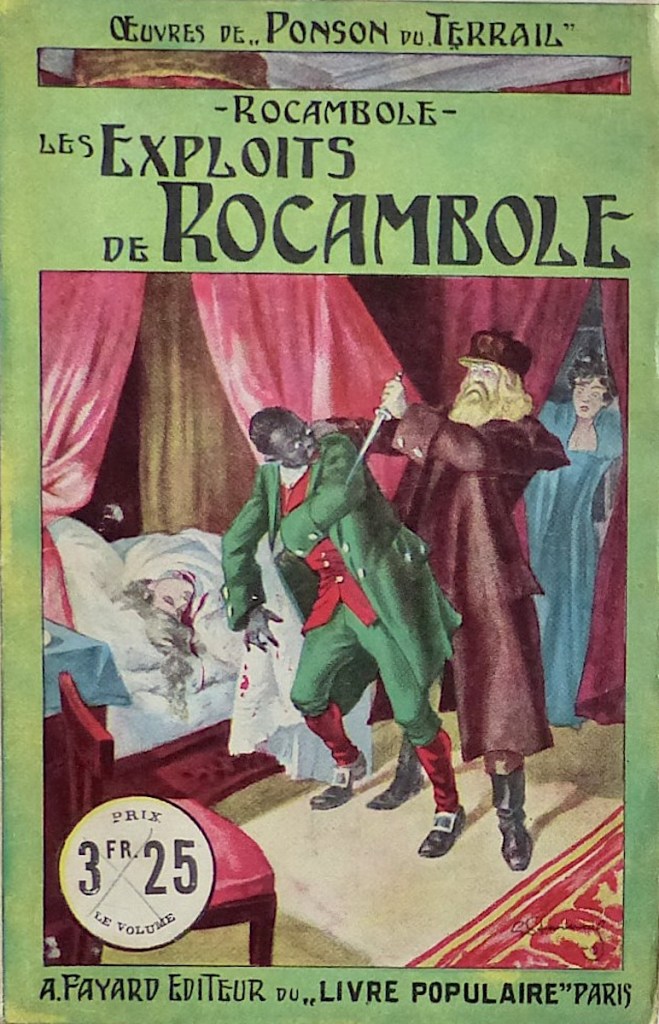

Ponson du Terrail, Les Exploits de Rocambole, Series “Le Livre Populaire” (Paris: Arthème Fayard, 1909). Cover by Gino Starace. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The criminal antihero Rocambole takes center stage in Les Exploits de Rocambole. Following a shipwreck off the coast of northern France, Rocambole steals the identity papers of the Marquis Albert de Chamery and abandons the unconscious aristocrat to perish on the shoals. Bearing a physical resemblance to the Marquis, Rocambole installs himself in the de Chamery apartment in Paris and commences to embezzle the family’s fortune.

Sir Williams reappears, now bearing tattoos and scars from burns inflicted upon him by Australian aboriginals (rather than Brazilian savages). But the génie du Mal has been reduced to a pathetic blind, deaf, and mute figure, who can only communicate through handwritten notes. Now, Rocambole steps forward as the architect of criminal schemes. He is so conniving, immoral, and violent that he kills everyone who might expose him as the false Marquis de Chamery, including the Marquise de Chamery, the family butler, and even Maman Fripart and Sir Williams.

The basic plot of the novel revolves around a proposed marriage between the false Marquis de Chamery (Rocambole) and the Spanish princess Conception de Sallandrera. When the Countess Artoff discovers the real Albert de Chamery has been wrongly imprisoned in Cadiz, she sees the hand of Rocambole behind it. Promising to assist in the marriage scheme, Artoff lures Rocambole to her Spanish residence.

Instead, the Countess captures Rocambole and orders her private executioner to disfigure his face with acid. In defeat, Rocambole is imprisoned, and the real Marquis de Chamery and the Princess Conception de Sallandrera properly marry. Yet while the ending of the novel preserves the trappings of social restitution, the installments overflowed with the outrageous criminal and murderous exploits of Rocambole, more popular than ever with a mass-reading audience.

With the next novel in the series, Les Chevaliers du Clair de Lune, Ponson misstepped. In this installment, Ponson turned the brutally scarred Rocambole into the shadowy behind-the-scenes schemer of a criminal gang, “The Knights of the Full Moon,” a role reminiscent of the now defunct Sir Williams. Readers made it clear through diminished newspaper sales that they preferred a handsome and energetic Rocambole to a disfigured and sequestered one. Within two years, La Patrie discontinued the series, and Ponson’s relationship with the newspaper ended.

Yet the criminal antihero Rocambole remained as popular as ever with readers. Concurrent with the initial newspaper run of Les Drames de Paris, and in the subsequent years, multiple publishers reissued the Rocambole novels in magazine installments and as bound books. Ponson gladly accepted the additional income and shifted his efforts toward writing other feuilleton novels, most notably the multi-volume historical series La Jeunesse du Roi Henri (“Young King Henry,” 1859-1868). Yet he was not yet done, my any means, with Rocambole. La suite au prochain numéro… (to be continued).

NOTES

[1] Novels in Les Drames de Paris series: L’Héritage mystérieux (1857); Le Club des Valets de cœur (1858); La Revanche de Baccarat (1859); Les Exploits de Rocambole (1859); Les Chevaliers du Clair de Lune (1860-1862).

[2] S.v. “Rocambolesque,” in Larousse du XXe siècle (Paris: Librarie Larousse, 1930). All translations from French throughout this post are those of the author.

[3] For example: Xavier Montépin, Les Viveurs de Paris (“The Survivors of Paris,” 1857); Lucien Guéroult, Les Bas-fonds de Paris (“The Paris Underworld,” 1870); Clémence Robert, Les Mendiants de Paris (“The Beggars of Paris,” 1872); Pierre Zaconne, Les Mansardes de Paris (“The Garrets of Paris,” 1880); and, Émile Gaboriau, Les Esclaves de Paris (“The Slaves of Paris,” 1885), among others.

[4] Jean-Luc Buard, “Pourquoi il fallait appeler notre bulletin Le Rocambole,” Le Rocambole, Bulletin des Amis du Roman Populaire no. 1 (Spring 1997): 11.

SOURCES

Régis Messac, Le “Detective Novel” et l’influence de la pensée scientifique (Paris: Honré Champion, 1929; revised edition, Paris: Éncrage/Les Belles Lettres, 2011). Parenthetical citations are from the 1929 edition.

Pierre Alexis Ponson du Terrail, Rocambole: L’Héritage mystérieux, vols 1 & 2, and Le Club des Valets de cœur, vol. 3 (Bruxelles: Éditions Complexe, 1991).

_____. Les Exploits de Rocambole, Collection “Bouquins” (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1992).

_____. “La Vérité sur Rocambole” (1867), facsimile reprint in Ponson du Terrail: Éléments pour un histoire des textes , ed. René Guise (Nancy: Centre de Recherches sur le Roman populaire, 1986).

Updated: June 14, 2025

Robin Walz © 2025

Leave a comment