Lacenaire (Marcel Herrand, left) and Count Édouard de Montray (Louis Salou, right) in Les enfants du paradis, directed by Marcel Carné (Pathé Studios, 1945). Photo: Children of Paradise (Les enfants du paradis), The Criterion Collection DVD (2012).

It only took the criminal court three days to convict Lacenaire of theft, murder, and attempted murder. In that same brief passage of time, he emerged as a popular media celebrity. Both the courtroom audience and the press were fascinated by Lacenaire’s disturbing combination of horrific crimes and his air of bourgeois respectability.

Pending his execution, Lacenaire cultivated his self-image as a “poet-assassin.” In La Force prison awaiting trial, Lacenaire returned to his literary métier, preparing a prospectus for his memoirs. In the two months in La Conciergerie prison following his death sentence, he completed his memoirs, composed new poems and revised earlier ones. Lacenaire’s Mémoiress with appended poems were posthumously published in 1836, shortly after he and Avril were executed by guillotine on January 9.

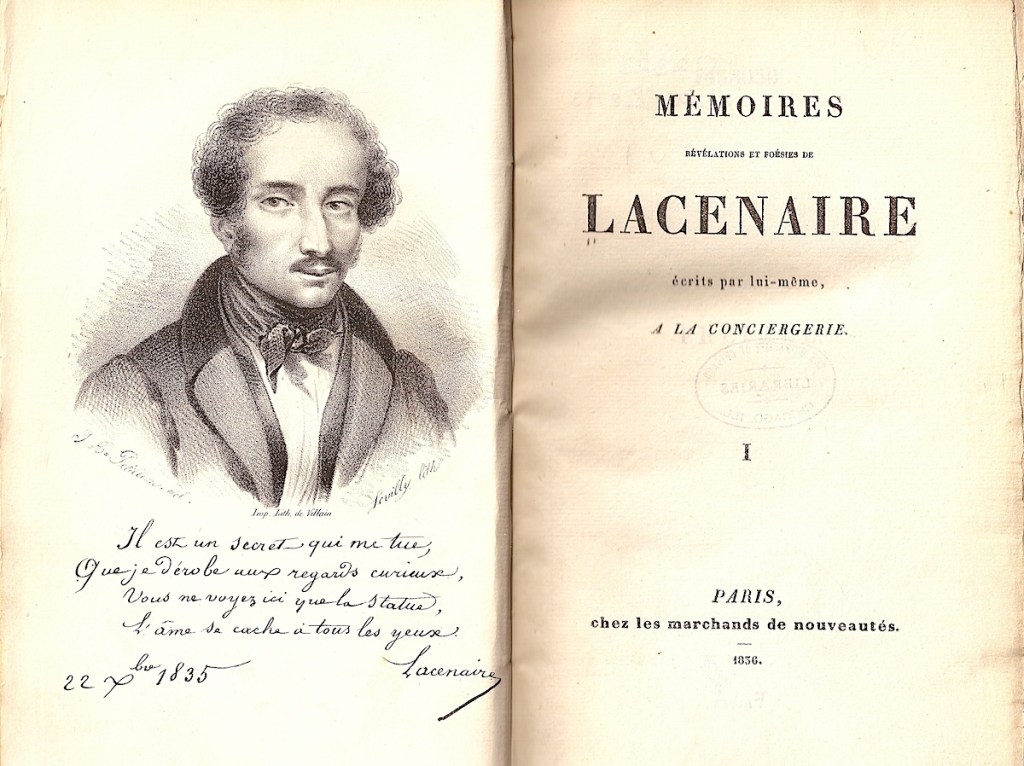

Frontispiece portrait by Levilly and the title page in Lacenaire, Memories, Revelations and Poems, written by himself in La Conciergerie (Paris: Chez les marchands de nouveautés, 1836). Inscription: “There is a secret killing me, / Which I conceal from curious gawkers, / You only see my likeness, / My soul stays hidden from all eyes.” Signed, Lacenaire, November 22, 1835. Collection: Bibliothèque des littératures policières, Paris.

While in La Conciergerie, Lacenaire received visitors in his cell and granted interviews to investigators, journalists, and socialites. One was Reffay de Luisignan, a Jesuit priest and his former schoolteacher. In Lacenaire après sa condemnation (“Lacenaire after his conviction,” 1836), the priest recounted their conversations, tinged with dark humor.[1] According to the priest, Lacenaire wanted the final page of his memoir to read, in capital letters: “LA SUITE À DEMAIN” (“NEXT INSTALLMENT TOMORROW,” p.4). Lacenaire was also enchanted by the three syllables in “guillotine,” although he wasn’t certain how the device worked: “I’ll study it one day, and let you know” (p. 27).

Lacenaire insisted that he was not a ladies’ man, sexual seducer or libertine, and that he derived no pleasure from the act of murderer. When Reffay inquired about three elegantly dressed Englishwomen who had visited him in his cell, Lacenaire responded, “They completely bored me, come to stare at me like an elephant in a cage” (p. 28).

Pressed about whether he had insatiable sexual and morbid appetites, Lacenaire replied, “After my death, I bet it will be widely published that I committed fifty murders. Don’t be surprised to learn that, hundreds of miles from Paris, I fed on children steaks. Humans, what a pathetic species!” (p. 95).

When Reffay compared him to Robert Mcaire, Lacenaire rejected the notion:

“I’ve seen Robert Macaire and the Auberge des Adrets, despicable crime dramas that disgust me — Robert because of his ostentation, the other by its stupidity. Murder is never a laughing matter. Kill in cold blood, that’s my motto and method. Killing for pleasure is a stupid gratification” (p. 45).

Lacenaire also had extended conversations in his cell with Paris police inspectors Allard and Louis Canler, who conducted the investigations that led to his arrest. As in court, Lacenaire affirmed his full participation in planning and carrying out the robberies and murders in the Cheval-Rouge Pasageway and Rue Montogeuil apartments. He also repudiated the false testimony given by Avril and François, considering their respective sentences of execution and perpetual hard labor just punishments for their betrayals.

Canler, a dedicated police functionary and future Chief of the Paris Sûreté, said it was a good thing for humanity that there were very few cold-blooded men like Lacenaire in society. The criminal ironically replied, “Shouldn’t you say that this society, against which I have declared war and maintain an implacable hatred, will be all too happy to see my head roll?”[2]

As an addendum to his Mémoires, Lacenaire added poems, some new and others previously published. Those composed in the weeks before his impending execution were particularly dark. The most famous, “Dans la lunette” (“On the guillotine”), is written in argot and dedicated to la pègre, the criminal underworld:

Thieves, cowards, all wanting your share of the loot

Lend an ear to my rude rant

You start by picking pockets

Then trembling with fear contemplate murder

The moment comes

You lose your head

Call it off, grab what you can, and split the scene

Someone denounces you

And soon the crowd

Comes to watch the guillotine fall, laughing.

Lacenaire, “On the Guillotine,” 1836. [3]

When Lacenaire faced execution, press coverage varied on how he met his fate. La Gazette des Tribunaux reported that, despite his courtroom witticisms and the celebrity status achieved during his final weeks of imprisonment, in the moments before his execution Lacenaire went livid and faint: “He had announced that he wanted to address the crowd, but lacked the strength to do so; his knees buckled, his face crumpled, and he mounted the scaffold slowly, supported by the executioner’s assistants.”[4]

Other newspapers insisted that Lacenaire maintained an air of nobility and a calm demeanor up to the moment of death. As recounted by Reffay de Luisignan, “Before mounting the scaffold, he embraced Avril, encouraging him when his first steps seemed to fail. Then, he tranquilly gave himself over to the executioner” (p. 296).

“Execution of Lacenaire and Victor Avril in Paris on January 9, 1836. Curious details about the two famous murderers who carried out numerous crimes and committed many thefts.” Contemporaneous canard broadsheet by Cambin Printers (Paris, no date).

For decades to come, accounts disagreed on Lacenaire’s conduct during his execution. Twenty years after the event, an “at-the-scene” report by lawyer and journalist Victor Cochinat wove together elements of suspense and horror with Lacenaire’s imperious comportment:

Lacenaire slowly mounted the scaffold and adjusted his head in the guillotine’s bloody aperture.

He was in this dreadful position for over a minute — an enormous length of time for such a perilous moment! — waiting for the blade to slide down the grooves of the guillotine that imprisoned him. Then, in the middle of its fall toward his neck, the triangle jammed…

It had to be pulled back up!

As this happened, through great exertion Lacenaire lifted himself by the elbows to turn his head around and stared at the instrument of death, which seemed to recoil in horror before him.

Perhaps this sharpened his wits to deliver some ultimate and dismal comment, as his mouth formed to make a taunting jeer. But death cut short this final pleasantry from his pale lips. Part of his chin was carried away…. The Widow Chardon was avenged! [5]

State executioner Henri-Clément Sanson, who operated the guillotine, asserted that such theatrical accounts were patently false. “Until his final moment,” he observed, “this celebrated criminal maintained his sangfroid and was remarkably composed.”[6] Sanson found the execution unremarkable, lamenting that Lacenaire had wasted his intelligence and talents on futile criminal activities.

In examinations conducted after Lacenaire’s execution, legal and medical experts affirmed he was an inhuman and remorseless murderer. Yet his physiognomy, the reading of physical features to interpret a person’s character and psychology, consistently failed to yield an aberrant personality.

Plaster Bust of Pierre François Lacenaire. Attributed to James de Ville, c. 1836. Museum of History of Science, Cambridge, UK. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Journalist Victor Cochinat was confounded by Lacenaire’s autopsy report. He lacked the physique of a ferocious murderer, and his cerebrum indicated a highly developed intelligence over base appetites. A phrenological examination of his skull suggested Lacenaire possessed a gentle, sensitive, and spiritual nature, not at all that of a thief or murderer. Cochinat noted, however, that Lacenaire’s villainous, long, and skinny hands, with enlarged and thick tips, resembled snakes: “the kind of hands that murder old women in their beds” (p. 334).

The interpretation of the post-autopsy report by Parisian author, actor, and administrator Hippolyte Bonnelier derived nearly opposite characteristics from Lacenaire’s physical features.[7] Lacenaire’s hands, he insisted, were small and delicate, hardly those of a killer. Still, he noted some physical deformities: a twisted spine, arms poorly attached to the shoulders, a jaundiced face and weak chinned, deleterious features that Bonnelier imputed to enervation and moral weakness. A phrenological examination of Lacenaire’s forehead suggested contradictory cerebral impulses, a calm exterior that masked inner deformities. From an interview conducted before his execution, Bonnelier added that the staccato rhythm of Lacenaire’s voice indicated he was a cruel and emotionless killer.

Embellished accounts of Lacenaire’s thefts, murders, trial and execution continued to be imaginatively dramatized in causes célèbre magazines and books for the next century, sensationalized crime stories morally tinged with opprobrium. In reality, he was a bungling thief and botched murderer. Yet in the collective French imagination, Lacenaire’s image had been transformed into the “poet-assassin.”

Édmond Locard, The Guillotine’s Fiancé (Lacenaire), series “Les Causes Célèbres” (Paris: Éditions de la Flamme d’or, 1954). Collection: Bibliothèque des littératures policières, Paris.

According to French historian Anne-Emmanuelle Demartini, the Mémoires “played a decisive role in constructing a mythic persona for Lacenaire that married crime and literary style, under the auspices of the guillotine.”[8] A wide range of contemporary authorities, from jurists, doctors, and phrenologists to esteemed writers and journalists, concurred that Lacenaire was a monster. Yet his monstrosity was of a particularly modern sort, a contemporary hybridization of “humanity and inhumanity, good and evil, barbarism and civilization” (Demartini, p. 74; author’s translation).

In contrast to the criminal monsters that populated Bibliothèque bleue stories from the previous centuries — the half-human progeny of animals or the devil, countryside savages, urban vagabonds and beggars, or redoubtable bandits — Lacenaire’s demeanor suggested bourgeois civility, eloquence, and sophistication, albeit in a perverse fashion. Unlike other contemporary criminals from the dangerous classes of rural migrants, city paupers, and the working poor, Lacenaire came from a middle-class family with all the benefits of merchant wealth, a proper education, and religious instruction. Lacenaire’s modern monstrosity stemmed from his egoïsme, esteeming himself above society and its norms. This deformed bourgeois monstrosity in the guise of an eloquent assassin, Demartini emphasizes, was the remorseless criminal the state had to execute.

Unlike Vidocq, Lacenaire inspired few literary imitators. A notable exception is the character Valbayre from Stendhal’s unfinished novel, Lamiel (1839; posthumously published 1889).[9] Lamiel, the adopted daughter of a brutish village couple in Normandy, developed a passion in childhood for reading adventure novels about robbers and highwaymen. As a young woman, she became the companion of the Duchesse de Miossens, a locale notable. Her son, the Duc de Miossens, seduces and marries Lamiel, and together they whisk away to Paris. Once in the city, however, Lamiel turns the romantic tables on her husband by taking on her own lovers.

Stendahl’s rough draft of Lamiel remained unfinished in 1839. In notes left for its completion, he sketched out how Lamiel finds true love with a notorious thief named Valbayre, whose character was inspired by Lacenaire. Unfortunately, the author’s death in 1842 eclipsed Valbayre’s appearance (as well as the novel’s ending, in which Lamiel is consumed by a fire in the Palais du Justice).

While lacking direct imitators, the image of Lacenaire as a poet-assassin garnered approbation by the emerging literary avant-garde. Nineteenth-century poètes maudites (“accursed poets”), such as Charles Baudelaire, Lautréamont (Isodore Lucien Ducasse), and Arthur Rimbaud, refined and magnified the kinds of criminal impulses embedded Lacenaire’s Mémoires and poems, as well as his scandalous notoriety. Lacenaire was also celebrated by the Paris Dadaists and Surrealists in the early twentieth century.

Culturally, Lacenaire gained his greatest popular renown through the performance given by French actor Marcel Herrand in Marcel Carné’s cinematic magnum opus, Les enfants du paradis (Children of Paradise, 1945). In a filmscript penned by the poet and lyricist Jacques Prévert, an entirely fictionalized Lacenaire is a seductive and murderous dandy, who moves easily between tout Paris high society and the bas-fonds “lower depths” of the criminal underworld, rather than as an aloof poet-assassin. The charming and terrifying elegant criminal dominates the screen throughout the movie.

Movie Poster featuring Daniel Auteuil in Lacenaire (L’Élégant Criminel), 1990). Source: IMDb.

In director Francis Girod’s Lacenaire (L’Élégant Criminel, 1990), French actor Daniel Auteuil plays the poet-assassin. This slowly paced movie revolves around a series of prison cell conversations between Inspector Allard and Lacenaire, interspersed with flashbacks to his youth and scenes from his trial and execution. Girod downplays Lacenaire’s aloof and egotistical personality, indifferent to the horrific crimes he has committed, and instead transforms him into a social avenger with deep emotional attachments to a fictitious ward named Hermine and Avril as his lover-accomplice.

Even though Lacenaire did not generate a literary lineage, his peculiar combination of unbridled criminality and elegance inspired popular fiction writers who followed. From the mid-nineteenth century forward, the crime factory of serialized novels about elegant criminals and dark avengers shifted into high gear, churning out reams of stories about lurid crimes and prodigious criminals, elegant and not-so-elegant, in newspapers, magazines, and novels.

NOTES

[1] Lacenaire après sa condemnation, ses conversations intimes, ses poésies, sa correspondence, un drame en trois actes,[ed. Reffay de Luisignan] (Paris: Chez l’éditeur marchand, 1836). The following parenthetical citations, translated by the author, are taken from this sourse.

[2] Louis Canler, Mémoires de Canler, ancien chef du service de Sûreté (1882), ed. Jacques Brenner (Paris: Mercure de France, 1968), p. 203.

[3] Lacenaire, “Dans la lunette (À la pègre).” In argot: “Pègres, traqueurs, qui voulez tous du fade. / Prêtez l’esgourde à mon dur boniment : / Vous commencez par tirer en valde / Puis au grand truc vous marches en taflant. / Le pante aboule / On perd la boule /Puis de la taule on se crampe en rompant / On vous roussine / Et puis la tine / Vient remoucher la botte, en rigolant.” In Mémoires, ed. Lebailly, p. 345. In French translation: “Pègres poltrons qui voulez tous la part du vol, / Prêtez l’oreille à mon dur discours ; / Vous commencez par voler les poches, / Puis à l’assassinat vous marchez avec crainte, / La dupe vient / On perd la tête,/ Puis de la chambre on fuit en rompant / On [la police] nous arrête / Et puis la foule / Vient regarder la guillotine en riant.” In Émile Chautard, La vie étrange de l’argot (Paris: Denoúl et Steele, éditeurs, 1931), pp. 125-126. Author’s English translation.

[4] La Gazette des tribunaux, 10 January 1836. Reproduced in Mémoires, ed. Lebailly, p. 280. Author’s translation

[5] Victor Cochinat, Lacenaire, ses crimes, son procès et sa mort, suivis de ses poésies et chansons et documents authentiques et inédits (Paris: Jules Laisné, Libraire-Éditeur, 1857), pp. 334-335.

[6] H. [Henri-Clément] Sanson, Mémoires des Sanson, sept générations d’exécuteurs 1688-1847, vol. 6(Paris: Dupray de la Mahérie, éditeur, 1863), p. 504.

[7] Hippolyte Bonnelier, Autopsie physiologique de Lacenaire, mort sur l’échafaud le 9 janvier 1836, excerpted in Mémoires, ed. Lebailly, pp. 293-300.

[8] Anne-Emmanuelle Demartini, “L’infamie comme œuvre. L’autobiographie du criminel Pierre-François Lacenaire,” Sociétés et Représentations 13 (2002), p. 122. Author’s translation

[9] Jean Prévost, Essai sur les sources de Lamiel. Les Amazones de Stendhal. Le procès de Lacenaire, Doctoral thesis, Faculté des Lettres de Lyon (Lyon: Imprimeries Réunies, 1942). This paragraph summary is based upon the “Lamiel” entry on the French Wikipédia site (https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lamiel, consulted February 10, 2025).

SOURCES

Children of Paradise (Les enfants du paradis), directed by Marcel Carné (Pathé Studios, 1945, 190 minutes). DVD The Criterion Collection (2012).

Anne-Emmanuelle Demartini, L’affaire Lacenaire (Paris: Aubier, 2001).

Pierre-François Lacenaire, Mémoires, révélations et poésies de Lacenaire écrits par lui-même, à la Conciergerie, 2 vols. (Paris: Chez les Marchands de Nouveautés, 1836).

Lacenaire (L’Élégant Criminel), directed by Francis Girod, starring Daniel Auteil and Jean Poiret (UGC/Ciné 5/Hachette Première, 1990, 125 minutes).

Updated: March 27, 2025

Robin Walz © 2025

Leave a comment