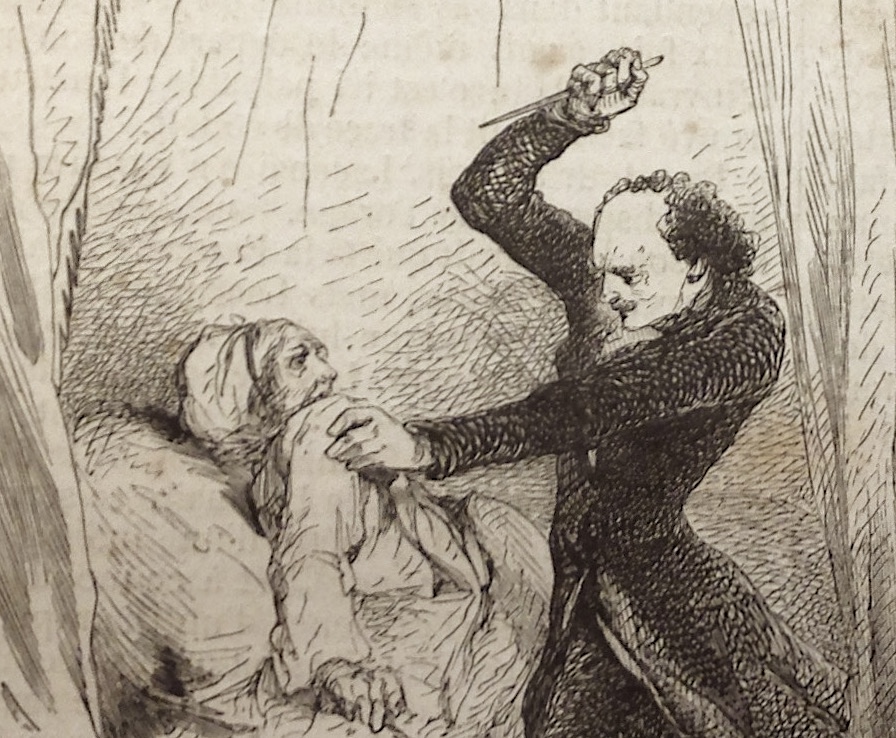

“Murder in the Cheval-Rouge Passageway” (detail). Causes Célèbres no. 7 (1859). Collection: Bibliothèque des littératures policiers, Paris.

When Pierre-François Lacenaire was arrested in January 1835, he was simply a criminal miscreant, yet another thief soon to go on trial for murder. That November, however, courtroom coverage by multiple Parisian newspapers transformed him into a media celebrity.

In a pretrial article on November 7, Le Constitutionnel characterized Lacenaire as an emotionally detached freethinker and atheist, whom medical experts affirmed was extremely intelligent.[1] Once the trial was underway on November 12, Lacenaire fully admitted to his roles in the thefts and murders, never making any attempt at denial or exculpation. Newspaper journalists supplemented his testimony with commentaries that focused on his handsome appearance, elegance, and wit. For the reading public, Lacenaire was more than a common thief and murderer; he was the elegant criminal.

Profile portrait of Pierre-François Lacenaire. Lithograph by Pierre Théophile Junca, 1835. Collection: Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

As recorded in his Mémoires, Pierre-François Lacenaire was born in 1800 into an aspiring bourgeois family from Francheville, located in the Franche-Comté region of France between Burgundy and Switzerland. The disaffected second son of wholesale iron and silk merchant Jean-Baptiste Lacenaire, the family had invested its emotional and financial resources into their eldest, Jean-Louis. As a youth, Pierre-François rebelled against the family and developed a fiercely independent spirit. He scorned his father’s commercial ambitions, detested his doltish mother, ridiculed his hypocritical Jesuit teachers, and conned money from extended family members.

After completing secondary school, Lacenaire cycled through a number of meaningless entry-level jobs as a notary’s assistant, bank courier, political journalist, vaudeville playwright, and liqueurs salesman. He briefly joined the military in 1828, but deserted within the year. He even considered emigrating to America to make a fresh start, but lacked funds for the voyage

Having failed to make his way into professional, business, or literary worlds, Lacenaire turned to crime to make a living. This approach proved equally arduous and unrewarding. His first major theft in 1828 went awry. Hired to steal a horse carriage for a stolen goods dealer, Lacenaire was paid less than the prearranged sum. His role in the crime was quickly discovered, and in no time he was arrested by the police.

Sentenced to prison, Lacenaire feared the hardened inmates would discover he wasn’t from the milieu. Under these circumstances, Vidocq’s Mémoires proved useful as he recalled enough argot to pass undetected among the other prisoners until he had more fully absorbed their criminal slang and habits. Consecutively incarcerated at the Bicêtre, La Force, and Poissy prisons, Lacenaire was released in 1829, thanks to the intervention of a philanthropist who took pity upon him due to his weakened physical constitution from stomach ulcers.

Upon release, starving and broke, Lacenaire needed money as quickly as possible. The acquaintances he had made in prison were unreliable in the outside world, as ex-convicts would betray each other on a whim for the slightest financial gain. Rather than thieving for someone else, Lacenaire resolved to go it alone, convinced his intellect and determination were sufficient to guide his criminal activities. Over the next few years, he planned various thefts and cycled through a number of temporary accomplices, to guard against betrayal, to assist in carrying out his crimes.

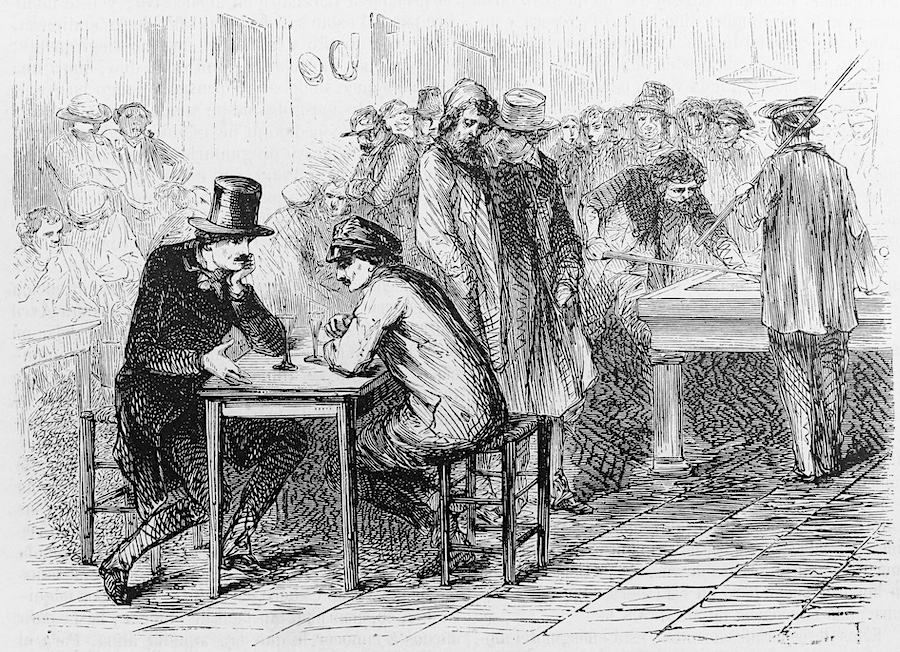

“Lacenaire and Avril in a tavern.” Illustration in Anales dramaticos del crimen, ó causas celebres Españoles y extranjeras, ed. José de Vicente y Caravantes, 5 vols. (Madrid: Fernando Gaspar, 1858-1866). Source: Wikipédia (fr.wikipedia.org).

Sometimes robberies could yielded thousands of francs, and briefly Lacenaire would live the high life. Yet the need for money was incessant. Seeking a more secure livelihood, once more he took a stab at living above board as a freelance writer, but the work was intermittent and paid poorly. To supplement his income, Lacenaire would disguise himself as a policeman to trap “honest gentlemen” into engaging in illicit sexual activity in alleyways along the Champs Elysées, and then extort money from them on the spot. For quick cash, he would skim restaurant tills, a high-risk activity that landed him in La Force prison for a second time in 1832 under the alias of Henry Gaillard, the surname on his mother’s side of the family.

Even before this latest round of imprisonment, Lacenaire had decided to add murder to his criminal activities, following the logic that major thefts are more likely to be successful when no witnesses are left behind. In practice, this approach proved ill-conceived as well.

In the first grand theft and murder attempt recounted in his Mémoires, Lacenaire and an accomplice referred to as “R…” targeted a man known to be a high stakes gambler, hoping to walk away with at least 100,000 francs. When R… stabbed the gambler during the robbery attempt on the rue Chaussé d’Antin, the victim cried out, “Murderers!” Lacenaire and R… panicked and fled, leaving the man alive and their pockets empty. Frustrated by the botched attempt, Lacenaire resolved to plan out his next crime more carefully.

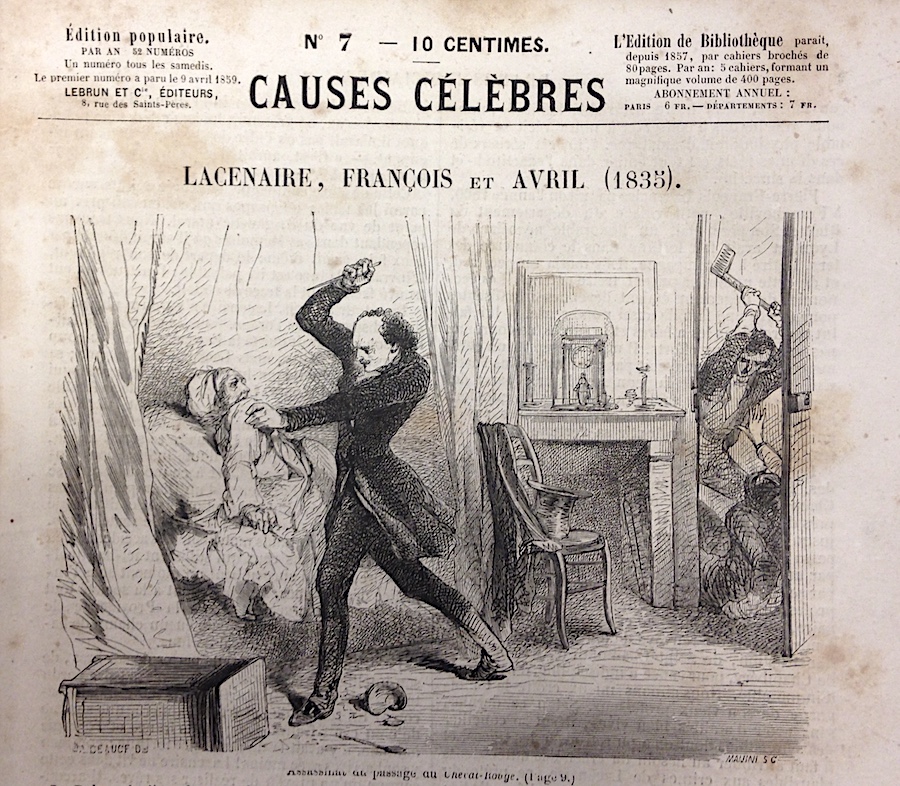

In November 1834, Lacenaire met up with one of his convict confrères, Victor Avril, whom he had met in Poissy prison. Together, they planned the robbery and murder of the widow Chardon, who lived in an apartment along the Cheval-Rouge Passageway off the rue Saint-Martin with her son, Jean-François, a male prostitute known as “Aunt Madeleine.”[2]

“Lacenaire, François et Avril (1835): Murder in the Cheval-Rouge Passageway.” Causes Célèbres no. 7 (1859). Collection: Bibliothèque des littératures policiers, Paris.

While also incarcerated in Poissy prison, Jean-François Chardon had regaled Lacenaire and Avril with stories about 10,000 francs his mother had stashed in their apartment, supposedly the collected savings from a charity hospital where she worked. On December 14, Avril and Lacenaire forced their way into the Chardon apartment and brutally murdered both mother and son. The spoils amounted to a mere 500 francs and some dining silver, a pittance in comparison to the imagined haul.

Shortly after, Avril was arrested after a bar brawl. Consequently, Lacenaire was forced to find a replacement accomplice for his next theft and murder scheme. He hired another convict acquaintance, Jules Bâton, to assist him in robbing a bank delivery messenger named Genevey. Under the alias of Mohossier, Lacenaire rented an apartment on the rue Montorgeuil. The plan was to lure the courier up to the room, where they would murder him and make off with the bank satchel containing cash deposits and bank notes.

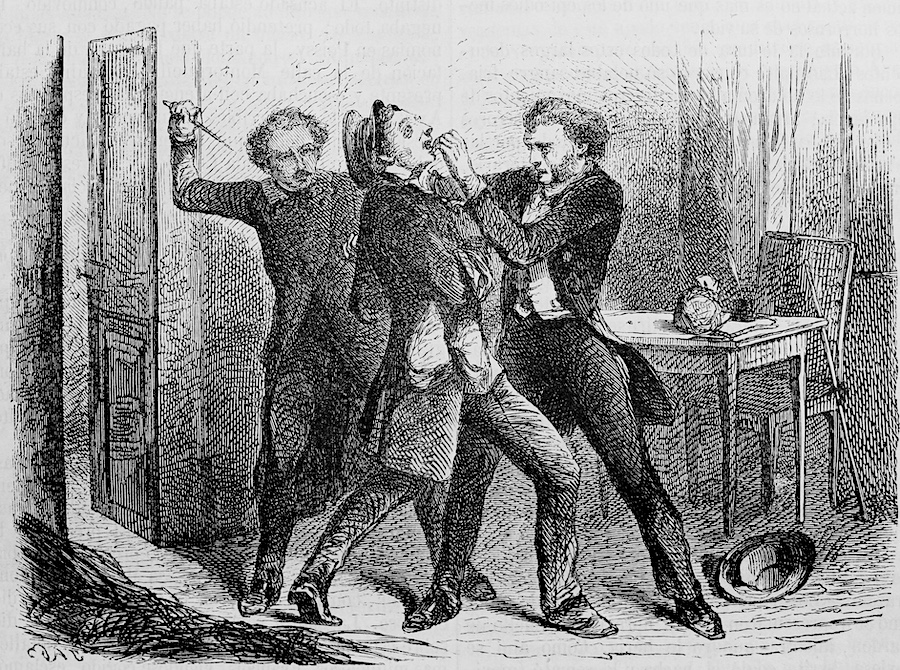

The evening before the plan was set into motion, however, Bâton backed out. In his place, Lacenaire engaged the services of another convict associate, Martin François. On the afternoon of December 31, when the bank courier messenger entered the apartment, François stabbed him in the shoulder with a sharpened file blade (tiers-point). The blow failed to kill Genevey, who screamed out, “Thief!”

Passersby heard his cries and started gathering outside. With the murder bungled, Lacenaire and François abandoned the wounded courier, grabbed his satchel, and ran out of the apartment building and into the street shouting, “Thief! Thief!” In the confusion, they escaped with 1,000 francs in cash and ten-fold that amount in bank notes.

“Attempted murder of bank messenger Genevay.” Illustration in Anales dramaticos del crimen, ó causas celebres Españoles y extranjeras, ed. José de Vicente y Caravantes, 5 vols. (Madrid: Fernando Gaspar, 1858-1866). Source: Wikipédia (fr.wikipedia.org).

Things went downhill, fast. When François was arrested the following week for the minor infraction of having stolen some bottles of wine, Lacenaire fled Paris to avoid being betrayed by his co-conspirator. Several days later in the city of Beaune in Burgundy, the police picked up a certain Jacob Lévi for cashing counterfeited Parisian bank notes. The Beaune police soon realized that Lévi was an alias.

With the bank notes as a lead, investigators looked into open criminal cases in Paris for possible connections. Might this be Gaillard, the suspect implicated in the Chardon murders? Or Mohossier, who had rented the apartment where the attempted murder and theft of the bank courier Genevey took place? Thanks to independent denunciations provided by Avril and François, each incarcerated at the time, the police learned that both of these aliases belonged to Lacenaire, who was returned to Paris and charged with theft, murder, and attempted murder.

At first, Lacenaire remained silent in the face of the accusations against him. Once he learned of the betrayals by Avril and François, however, he began to fully cooperate with the interrogating magistrate in the preparation of the state’s case against him. Lacenaire provided the prosecutor with detailed information about his participation in the planning and commission of the thefts and murders. He also detailed the roles Avril and François had played in the commission of those crimes. He even corrected errors in the prosecution’s dossier before it was submitted to the criminal court.

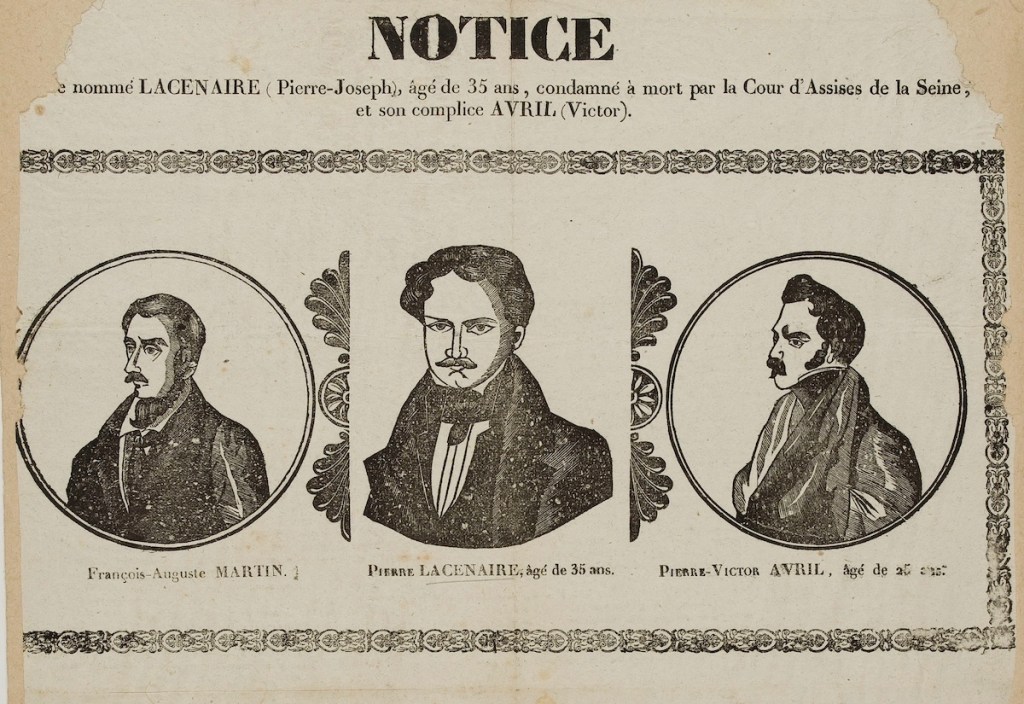

“NOTICE concerning LACENAIRE (Pierre Joseph), 35 years old, sentenced to death by Assize Court of the Seine, and his accomplice AVRIL (Victor).” Portraits printed on a canard broadsheet by Antoine Chassaignon (no date). Gallica: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

On November 12, La Quotidienne newspaper provided readers this description of Lacenaire’s appearance on the opening day of the trial:

Lacenaire is short, dresses in a blue double-breasted frock coat, displays a lively countenance, and has a fair complexion. His forehead indicates intelligence. His brown hair, parted on the side, suggests a hint of pretension. He sports a small brown mustache. His flashing eyes, constantly shifting, endows him with a peculiar combination of indifference and audacity. He seems to possess a sangfroid colored with cynicism, and is prone to laughter when conferring with his lawyer.[3]

In contrast to Lacenaire’s handsome appearance and elegant manners, journalists depicted his working-class co-defendants, the carpenter Victor Avril and the floor layer Martin François, as crude, impertinent, and prone to verbal outbursts in court. While each of the accused admitted to taking part in the thefts, Avril and François denied they had participated in the murders and placed the blame solely upon Lacenaire.

For his part, Lacenaire provided the court with detailed information, corroborated by witnesses, about Avril’s and François’s full involvement in both the thefts and murders, which confirmed the veracity of his testimony and subjected theirs to perjury. As the three-day trial progressed, the press depicted Avril and François as increasingly wan and defeated in spirit. Lacenaire, by contrast, remained self-possessed, tranquil, convivial, and witty.

The court delivered judgments against the trio on November 14: Lacenaire and Avril were sentenced to death by guillotine, and François to perpetual hard labor. Lacenaire maintained his composure and remained impassive as the judgements were read, although some newspapers reported he appeared somewhat drained and subdued.

Sensationalized press accounts about the thefts and murders in the Cheval-Rouge Passageway and the Rue Montorgueil apartment echoed the imaginary bloodbath from the Fualdès Affair, two decades earlier. The horrific crimes of Lacenaire, Avril, and François continued to be recycled in popular causes célèbres accounts for a century to come. Yet something remarkable and unexpected had occurred over the course of the three-day trial as well.

Like Lamaître’s remolding of Robert Macaire on the melodramatic stage, from a heartless thief and murderer into a humorous antihero, Lacenaire’s performance in the courtroom audience and the press transformed him into the image of the handsome and witty “elegant criminal.” Far from being a déclassé buffoon, however, Lacenaire personified the deformation of the respectable bourgeois into an alluring criminal. From within the chrysalis of his prison cell in La Conciergerie, Lacenaire completed this metamorphosis in the two months before his execution by writing his memoirs, composing sardonic poetry, and receiving socialite visitors in his cell.

NOTES

[1] “La presse dans tous ses états” in Mémoires, ed. Lebailly, p. 323. Excerpts in this edition from newspaper accounts of Lacenaire’s trial and subsequent execution include Le Constitutionnel, Le Gazette des tribunaux, Le Charivari, Le Bon sens, Le Courrier français, Le Gazette de France, Le Quotidienne, and Le Journal du commerce.

[2] “Tante Madeleine.” In French argot, tante (“aunt”) refers to a male homosexual who takes on a submissive role.

[3] Quoted in Mémoires, p. 326. Author’s translation.

SOURCES

Pierre-François Lacenaire, Mémoires, ed. Monique Lebailly (Paris: L’Instant, 1988).

Anne-Emmanuelle Demartini, L’affaire Lacenaire (Paris: Aubier, 2001).

Updated: January 31, 2025

Robin Walz © 2025

Leave a comment