Publicity poster for Vidocq, grand film en 10 épisodes, starring René Navarre (1923). Gallica: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

When considering Vidocq’s legacy, it is important to keep in mind he was not a Sûreté detective. The reason is simple: the Sûreté was only created in 1853, shortly before Vidocq’s death in 1857, long after his stints as security squad and special police chief for the Paris Prefecture’s Second Division. That said, colloquially his team was frequently referred to as the police de sûreté, and two hundred years of apocryphal accounts, popular crime fiction, movies and television series have forged the image of Vidocq into the legendary chef de la Sûreté.

It’s an understandable confusion, both linguistically and historically. The French word sûreté is a common noun translated into English as “safety” and “security.” When Vidocq was appointed chef de la brigade de sûreté in 1812, he became the leader of an ancillary “security squad” that assisted the police in tracking down criminals, gang leaders, and stolen goods dealers. The security squad was not officially incorporated into the Police Prefecture’s Second Division and lacked the authority to make arrests directly, which were performed by regular police agents. In the embellished and fictionalized Mémoires, Vidocq aggrandized himself as a “police chief” and exaggerated the activities of the security squad, which helped to cement his image as a redoubtable detective in the public imagination (see “Vidocq: From Con Man to Security Squad Chief”). In 1832, Vidocq was briefly the leader of the official and ill-fated police de sûreté (“security police”), which lasted less than a year after his squad was accused of excessive brutality and participating in crimes (see “Vidocq: Shady Detective”). Following these auxiliary appointments, Vidocq gained great renown and approbation as the owner of his own private police agency and through press coverage of his 1843 trial, conviction and reprieve. In any event, he was never a detective for the as-yet nonexistent Sûreté.

To complicate things further, since the late-eighteenth century an administrative office in Paris called the sûreté générale maintained police records and kept criminal files. The sûreté générale was only briefly charged with police authority on two occasions, first during the Reign of Terror during French Revolution (1792-1796) and later as an adjunct to the Ministry of the Interior (1816-1818), short stints that pale in comparison to a half-century of clerical duties. It was not until 1853, during the Second Empire of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, that the Sûreté générale (briefly the Sûreté publique) became an official branch of the police with detectives who investigated crimes for the judiciary and prosecuting magistrates. Over the subsequent decades, the authority and activities of the Sûreté were repeatedly augmented, and finally formalized as the Sûreté nationale in 1934. In the post-WWII era, in 1966 the Sûreté was renamed the Police nationale, its current designation today.

Still, in the popular imagination, Vidocq became a Sûreté detective of tremendous power and influence. This begins with a spate of tell-all exposés about the Paris Prefecture contemporaneous with the publication of Vidocq’s Mémoires, which reinforced public suspicions of widespread police corruption under the Bourbon Restoration. One of the most widely disseminated was La police dévoilée depuis la Restauration (“The Police since the Restoration Unveiled,” 1829) by “M. Froment,” whose reprint editions added “Vidocq, chef de la police de sûreté” to the title page.[1] Earlier that year, Froment promised readers the “unadulterated truth” about Vidocq in Histoire de Vidocq, in substance an abridgement of the Mémoires.[2] Vidocq’s ghostwriter Louis-François L’Héritier wrote Supplément aux Mémoires de Vidocq (2 vols., 1829), which promised no-holds-barred revelations “written by the editor of the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th volumes of the Memoirs,” but was actually a fictionalized sequel.[3] Both Froment’s and L’Héritier’s books were as embellished and fantastic as Vidocq’s Mémoires themselves, yet added weight to the notion that Vidocq was a shady detective who served the corrupt Second Division of the Police Prefecture.

As both criminal and detective, Vidocq’s character was readily transposed into fictional characters in the nineteenth century, first by Balzac in Ferragus, chef des Dévorants (“Ferragus, Leader of the Devourers,” 1833).[4] The romantic hero of the novel, Auguste de Maulincour, assists the “chief of the special police of Paris” and his agents in their pursuit of Ferragus, an escaped convict and leader of the secret “Devourers” criminal gang. Literary critics have long noted that Vidocq inspired Balzac’s fictional character Vautrin, a fugitive convict in Le Père Goriot (1835) and an undercover detective disguised as the priest Carlos Herrera in Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes (1838-1847). The Mémoires have also been credited for providing descriptions of the bas-fonds underworld in Eugène Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris (1842-1843), which Vidocq capitalized on by responding with his own Les vrais mystères de Paris (7 vols., 1844). Vidocq also served as the inspiration for Alexandre Dumas’s detective Monsieur Jackal in Les Mohicans de Paris (1854-1855). In Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables (1862), Vidocq was split into two characters, the reformed convict Romantic hero Jean Valjean and his detective nemesis Inspector Javert. Vidocq was transformed into the upright Sûreté investigator M. Lecoq in a series of romans judiciaires (proto-police procedural novels) by Émile Gaboriau, beginning with L’Affaire Lerouge (1865) through Monsieur Lecoq (1868).

Across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, French publishers reissued Vidocq’s Mémoires in multiple formats, most abridged. In the early twentieth-century, Belle Époque, private detective Eugène Villiod edited a two-volume collector’s edition of the Mémoires. In a previous book, Villiod had echoed Vidcoq’s claim that only private detective agencies, not the police, could protect honest society from the criminal element:

“One of the lamentable characteristics of our age is the terrifying progression of criminality.”

“The Sûreté agent is notoriously handicapped by a lack of resources, time, and money… constrained by bureaucratic routines that leave no room for individual initiative.” [5]

In the preface to the reissue of the Mémoires, Villiod expressed bewilderment about certain aspects of the detective’s life and career. He was perplexed by the emphasis upon Vidocq’s criminal activities before becoming chef de la police de sûreté, and he questioned the morality of employing former criminals and agent provocateurs as auxiliaries within the security squad. Villiod also bemoaned not having a visual portrait to evaluate Vidocq’s physiognomy, having to rely instead upon written descriptions to puzzle together an “honorable image” of the detective.[6] Yet despite Vidocq’s disreputable life as a criminal and convict, dubious career as a policeman, commercial misfortunes, and living in penury at the end of his life, Villiod insisted that he displayed iron will as a detective who fought back in the “struggle for life.”[7] Such adulation on Villiod’s part was largely an act of commercial self-promotion, as he owned and operated one of the most successful private detective agencies in Paris in the early twentieth century (addressed in later blog posts).

French popular memory of Vidocq, by contrast, has delighted in the doubled aspect of Vidocq’s character as con man and detective. This is made abundantly clear in French movies and television series about Vidocq produced over the past century.

“Vidocq, A Wild and Burning Love.” Ciné-Miroir no. 20 (February 15, 1923). Collection: Bibliothèques patrimoniales, Paris. Public Domain.

The first major film release from the silent era was Vidocq, grand film en 10 épisodes (“Vidocq, A Major Motion Picture in 10 Episodes,” Pathé-Consortium-Cinéma, 1923). The serial starred René Navarre, a popular French movie star previously featured in two crime series as the archvillain Fantômas and as the convict Palas, who escapes from Devil’s Island with the criminal-avenger Chéri-Bibi.[8] The plot of Vidocq centers upon the detective’s pursuit and capture of the Enfants du Soleil (“The Sun’s Children”) criminal gang and their leader L’Aristo (“The Aristocrat”). Humorous members of Vidocq’s security squad featured in the film include Coco Lacour (“Coco the Flirt”) and Bibi la Grillade (“Grilled Meat, That’s Me!”), with actress Elmire Vautrier co-starring as Vidocq’s romantic love interest, Manon la Blonde (“Blond Manon”). As is the case with many films from the silent era, no copy survives, although splendid programs distributed upon the release of each episode remain, as well as feuilletons penned by film script co-author Arthur Bernède published in Le Petit Parisien newspaper and the photo-illustrated Ciné-Mirroir magazine.

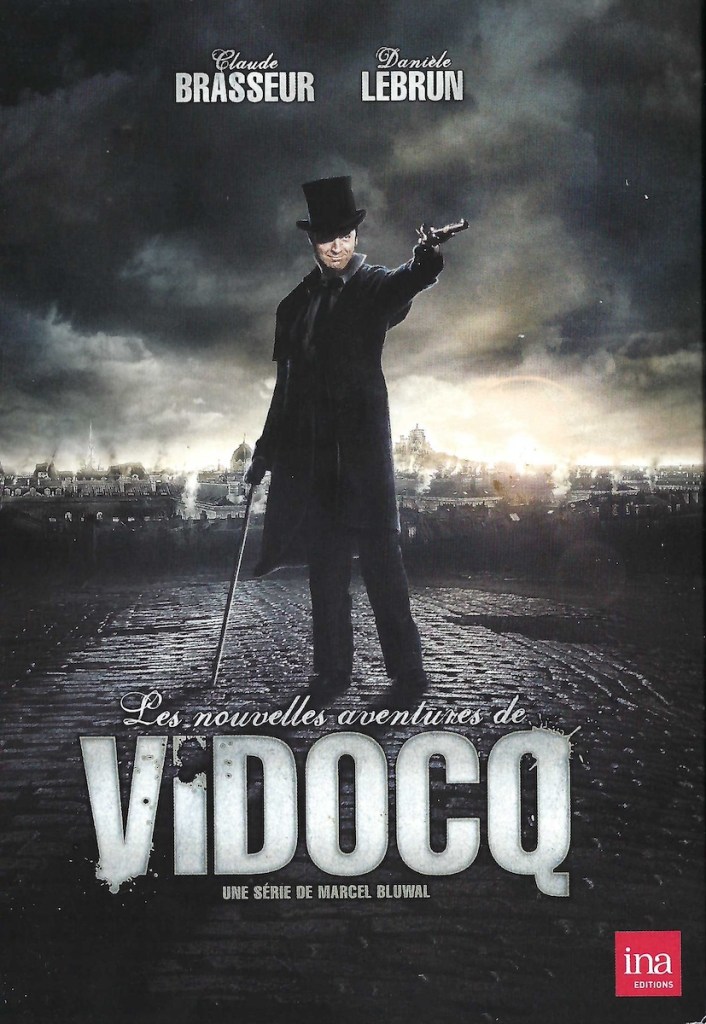

Vidocq’s character has been most deeply imprinted upon popular French memory through a television series from the 1970s, Les nouvelles aventures de Vidocq (“The New Adventures of Vidocq”), starring César award-winning actor Claude Brasseur. In thirteen episodes, with original scripts by Georges Neveux of the Académie Française, Vidocq leads his security squad of convict misfits on multiple adventures to capture criminals and to foil the political intrigues of the Baroness de Saint Gély. The series buys into Vidocq as the head of la police particulière de Sûreté (“Special Security Police”), conflating the original security squad of 1812 with the later security police designation created briefly in 1832. The series delights in the shady escapades of Vidocq and his squad, who employ their full repertoire of skills and deceptions acquired as criminals in the pursuit of malefactors. In this regard, Les Nouvelles aventures de Vidocq invokes the doubled aspect of Vidocq’s legend, as both lifelong con man and clever detective, avidly consumed by television audiences.

Two French feature films about Vidocq have been released in the twenty-first century, each original productions only loosely inspired by the great detective and having nothing to do with his historical or cultural legacy. Vidocq (2001), the first feature film made by special-effects director Pitof (Jean-Christophe Comar), is a mishmash of sci-fi, suspense, and horror genres, starring Gerrard Depardieu as private detective Vidocq. The plot revolves around the pursuit of “The Alchemist,” whose reflecting mirror mask sucks the life force out of his victims before he kills them by slitting their throats.

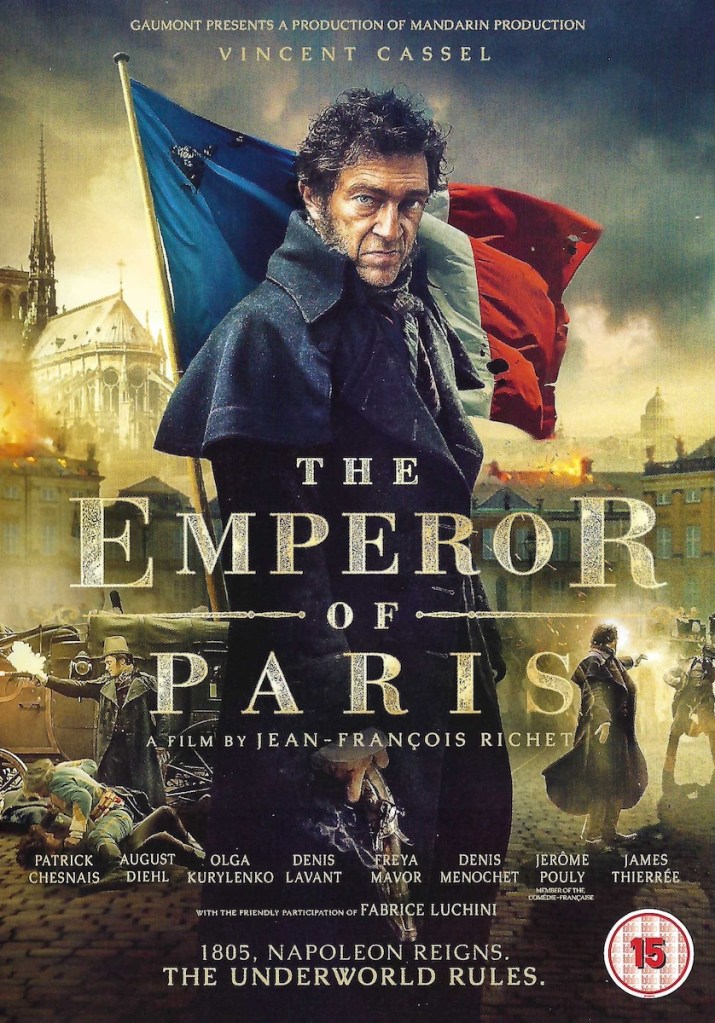

More recently, Vincent Cassel stars as Vidocq in The Emperor of Paris (2018), an action thriller and romance movie. An invented historical timeline locates the story in Paris in the early Napoleonic era. The plot revolves around the swashbuckling rogue Vidocq, who demonstrates his worthiness to the police by pursuing and violently killing criminals in exchange for his freedom, with a romantic liaison subplot. Despite the efforts of Gaumont Studios to promote the movie internationally — “Poldark meets Game of Thrones” (DVD cover) — the blockbuster production performed poorly at the box office

In English-language accounts of Vidocq, the “from convict to detective hero” interpretation has reigned supreme. One of the more imaginative and specious claims is that Vidocq was an innovator in the fields of criminology and police forensics. In fact, Vidocq did not invent the practice of assembling criminal files, which was already the purview of sûreté générale record keeping. Neither did he pioneer techniques of evidence collection; his method was to infiltrate the criminal milieu and ferret out at-large criminals, rather than expose culprits through a combination of trace evidence and logic. The great French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon and foundational forensic expert Dr. Édmond Locard later went to great lengths to dispel such claims and to distance both criminology and police science from the “Vidocq syndrome” (discussed in later blog entries).

English language biographies of Vidocq tend to be hagiographies, exalting his exploits as a detective while underplaying his criminal record and continuing illegal activities. This is particularly evident in John Philip Stead’s Vidocq, a Biography (1953) and Samuel Edwards’s The Vidocq Dossier (1977), mid-twentieth-century apocryphal accounts that thoroughly conflate the man and his legend, always to Vidocq’s benefit against his critics. These biographies are riddled with errors and inventions, and may be the primary English-language sources of recycled false claims about Vidcoq’s accomplishments. Mike Ashley provides a more balanced biographical sketch of Vidocq in the revived Strand Magazine (2000), viewing his shady career with a skeptically raised eyebrow, while affirming his status as a “great detective.”

The best biography available in English is James Morton’s The First Detective: The Life and Revolutionary Times of Vidocq, Criminal, Spy and Private Eye (2004). Author of multiple popular biographies on historical figures, Morton makes good use of both primary and secondary sources to construct his narrative, although a tendency toward bravado remains by floating Vidocq’s life story upon the historical currents of the times. Morton’s biography is particularly useful in its discussion of Vidocq’s high-society engagements in England and Belgium, 1846-1847, while on a tour to promote himself as a virtuoso detective. In America, the Vidocq Society of Philadelphia epitomizes the apogee of Vidocq adulation, a private association of retired detectives and forensic experts whose stated mission is to solve cold cases, but whose members gather primarily to enjoy gourmet meals and each other’s company.

Over two centuries, the heroic character of the grand détective Vidocq has been fashioned by detractors, enthusiasts, and imitators. Curiously, one of Vidocq’s earliest admirers inspired by the Mémoires was not a fellow detective, but the poet-assassin Lacenaire, the “elegant criminal” who saw his vocation as the egotistical elevation of himself in a perpetual war against society.

FURTHER READING

Vidocq’s Mémoires translated into English (in order of publication): Memoirs of Vidocq, principal agent of the French police until 1827 and now proprietor of the paper manufactory at St. Mandé (London: Hunt and Clarke, 1828); Memoirs of Vidocq, Principal Agent of the French Police until 1827, written by himself, translated from the French (Philadelphia and Baltimore: Carey, Hart & Co., 1834; continually reissued by multiple publishers throughout the nineteenth century); Vidocq: The Personal Memoirs of the First Great Detective, trans. Edwin Giles Rich (Cambridge, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1935; highly abridged in one volume); and, Memoirs of Vidocq: Master of Crime (Edinburg, London, and Oakland: AK Press/Nabat, 2003; a reissue of Giles Rich’s translation with updated commentary).

Biographies in English (in order of publication): Edward A. Hodgetts, Vidocq: A Master of Crime (London: Selwyn & Blount, 1928); John Philip Stead, Vidocq, a Biography: Picaroon of Crime (London and New York: Staples Press, 1953); Samuel Edwards, The Vidocq Dossier: The Story of the World’s First Detective (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977); Mike Ashley, “François Eugene Vidocq,” series “The Great Detectives,” The Strand Magazine, Issue IV (April-July 2000): 39-41, available online as “The Great Detectives: Vidocq”); and, James Morton, The First Detective: The Life and Revolutionary Times of Vidocq, Criminal, Spy and Private Eye (London: Ebury Press, 2004).

NOTES

[1] La police dévoilée depuis la Restauration et notamment sous Messieurs Franchet et Delavau, par M. Froment, ex-chef de brigade du cabinet particulier du Préfet, 3 vols. (Paris: Lemonnier,1829). Other contemporaneous exposés about the Paris police and Vidocq include: Louis Guyon, Biographie des commissaires de police et des officiers de paix de la ville de Paris, suivie d’un Essai sur l’art de conspirer et d’une Notice sur la police centrale, la police militaire, la police du château des Tuileries, la police de la Garde Royale, la police de la place, la police des Alliés, les inspecteurs de police, la gendarmerie, les prostituées de la capitale, Vidocq et sa bande (Paris: Mme Goullet, 1826); Antoine Année, Le Livre noir de MM. Delavau et Franchet ou Répertoire alphabétique de la police politique sous le minister deplorable d’après les registres de l’administration, précédé d’une introduction, 4 vols. (Paris: Moutardier, 1829); and, Antoine Gilbert Claveau, De la police à Paris, de ses abus et des réformes dont elle est susceptible, avec documents anecdotiques et politiques pour servir à l’histoire politique et judiciaire de la Restauration (Paris: A. Pillot, 1831).

[2] Histoire de Vidocq, écrite d’après lui-même par M. Froment du cabinet particulier du Préfet, 2 vols. (Paris: Lerosey, 1829).

[3] [Louis-François L’Héritier], Supplément aux Mémoires de Vidocq ou dernières révélations sans réticence par le rédacteur des 2e, 3e et 4e volumes des Mémoires, 2 vols.(Paris: Bouilland, 1830).

[4] Sylvie Thorel-Cailleteau, “Le ‘Roman de Vidocq’: étude d’un genre,” Nord’, revue de critique et de création littéraires du Nord/Pas-de-Calais, no. 46 (November 2005): 63-88.

[5] Eugène Villiod, Comment on nous vole, comment on nous tue, series “Les plaies sociales” (Paris: Maison d’Édition, 1905), pp. 1-3. Author’s translation.

[6] On this score, Villiod was mistaken, or simply wanted to avoid the issue, as both the frontispiece portrait by Marie Gabrielle Coignet in the Mémoires published by Tenon and the famous engraving by Achille Devéria were completed in 1828 and widely circulated.

[7] Villiod, “Préface,” Mémoires, p. xi. Author’s translation. The English phrase “struggle for lifer” [sic.] appears in Villiod’s French text.

[8] Fantômas, directed by Louis Feuillade (5 films, Gaumont Studios, 1913-1914) and La Nouvelle Aurore, directed by Émile-Édouard Violet (Studio Éclipse, 10 episodes, 1919).

SOURCES

Alain Carou et Matthieu Letourneux, Cinéma, Premiers crimes (Paris: Paris bibliothèques, 2015).

The Emperor of Paris, directed by Jean-François Richet, starring Vincent Cassel (Gaumont, 2018).

Clive Emsley, “From Ex-Con to Expert: The Police Detective in Nineteenth-Century France,” in Police Detectives in History, 1750-1950, ed. Clive Emsley and Haia Shpayer-Makove (London: Routledge, 2006).

Jay Kirk, “Watching the Detectives: The Vidocq Society’s tale of ratiocination,” Harper’s Magazine (August 2003): 61-71.

Les nouvelles aventures de Vidocq, starring Claude Brasseur, directed by Marcel Bluwal, written by Georges Neveux, 13 episodes (Gaumont, 1970-1971).

Graham Robb, “Files of the Sûreté,” in Parisians: An Adventure History of Paris (New York: W. W. Norton, 2010).

“Sûreté générale (puis nationale),” in Histoire et dictionnaire de la police du Moyen Âge à nos jours, ed. Michel Aubouin, Arnaud Teyssier and Jean Tulard, Collection “Bouquins” (Paris: Robert Laffont, 2005).

Eugène-François Vidocq, Mémoires, introduction by Eugène Villiod, 2 vols.(Paris: Garnier Frères, 1911).

Vidocq, directed by Pitof, starring Gérard Depardieu (Films Seville, 2001).

Updated: January 11, 2026

Robin Walz © 2024

Leave a comment