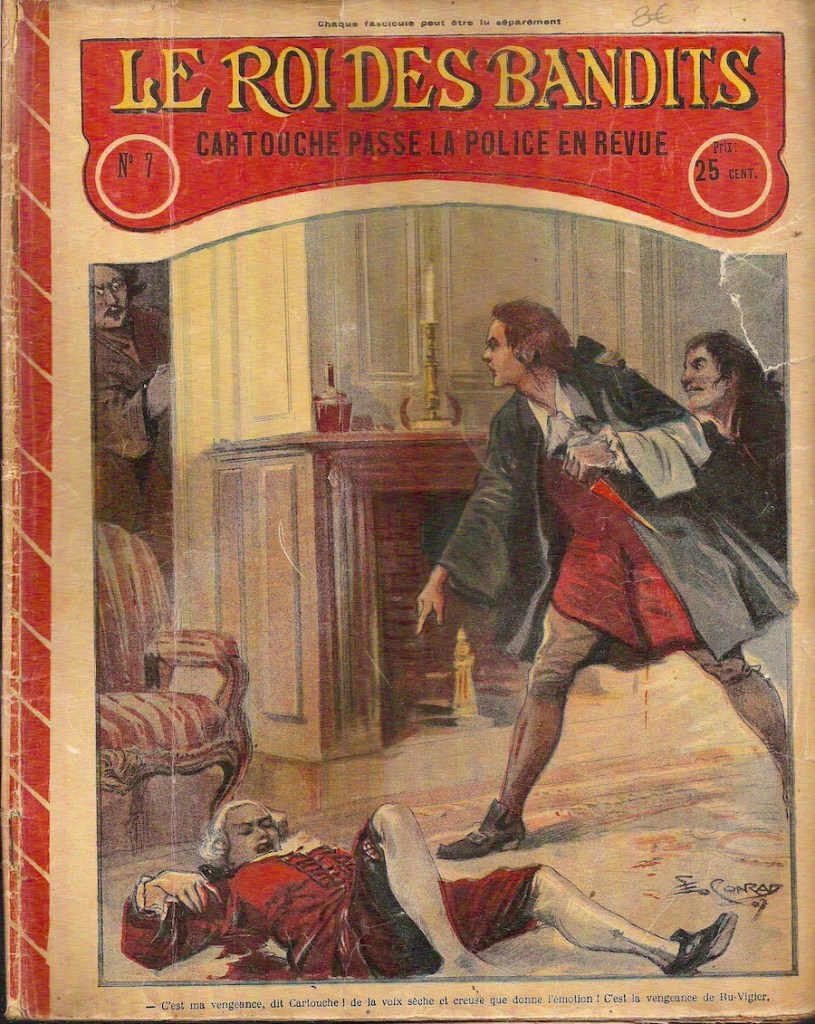

Jules Beaujoint (pseudonym), Cartouche, King of the Bandits, 25 issues (Paris: Arthème Fayard, 1907). Author’s collection.

Vidocq’s self-reference to the eighteenth-century bandit Cartouche in the preface to the Mémoires was on the mark. His narrative parallels the life and exploits of Cartouche: the child who first steals at home, runs away from his family, learns the wiles of gypsies and thieves, becomes a master of disguise and false identities, moves easily between the lowest and highest ranks of society, and is repeatedly arrested, incarcerated, and escapes from prison. The accounts diverge, however, in the consequences they bear for their criminal activities. Whereas Cartouche was absolved of his crimes through final confession and supplication before his execution, Vidocq was spared redemptive punishment. Instead, he recuperated his criminal talents to become a detective hero. In this way, the Mémoires modernize the Cartouche formula: in place of the tragic bandit, Vidocq became the duplicitous police agent who betrays the criminal milieu to achieve personal fame and fortune, fleecing his benefactors all the while.

French stories about criminals who fascinate, terrify, and titillate readers stretch back to the Bibliothèque bleue (“Blue Library”) from the sixteenth century. These were small-format chapbooks whose pages were bundled in the same blue-gray paper used to wrap loaves of sugar. They were printed on large sheets of poor quality paper and folded two, three, or four times along a common spine, called a signature, to produce a pamphlet between eight and thirty-two pages (lengthier books combine multiple signatures). Bibliothèque bleue chapbooks were distributed by colporteurs or itinerant peddlers, who hawked printed crime stories to villagers in the countryside and along city streets. The literate among them would read the chapbooks aloud to share their contents with others in the community.

One of the earliest published collections of crime stories in France is La vie genereuse des marcelots, gueuz et boesmies, contenans leur façon de vivre, subtilitez et Gergon. Mis en lumière par Monsieur Pechon de Ruby, Gentil’homme (“The generous life of peddlers, beggars and bohemians, including their manner of living, wiles and criminal jargon. Brought to light by Monsieur Pechon de Ruby, Gentleman,” 1596).[1] The presumptive author, the aristocratic-sounding Pechon de Ruby, promised readers revelations about a subterranean counterculture of vagabonds, rogues, and gypsies, as he had personally observed them over the course of a lifetime. Pechon de Ruby assured readers that those who carefully studied these pages would gain insider knowledge about the customs and language of these shifty wanderers as form of self-protection against their swindling activities. “Méfiez-vous!” Stay away from such types! Like any carnival barker, Pechon de Ruby pitched his chapbook to an audience simultaneously terrified and fascinated by sensationalism.

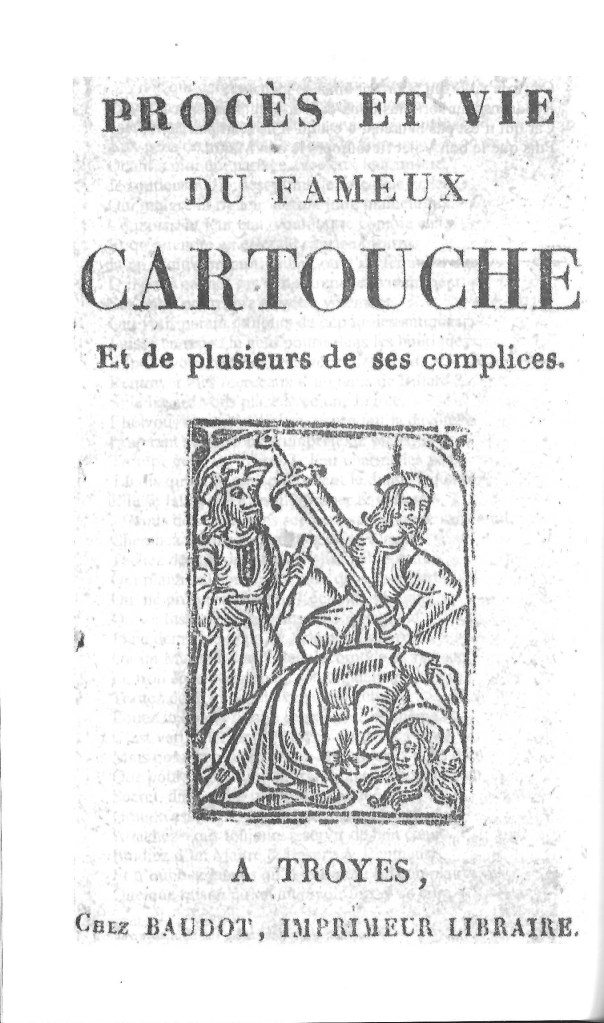

By the eighteenth century, the Bibliothèque bleue included tales about contemporary brigands who were transformed into popular heroes, the most famous among them being Cartouche. Born in 1693, Louis-Dominique Cartouche was the son of a Parisian wine barrel cooper who had turned to a life of crime as a boy. His brief career as a thief and criminal gang leader ended in 1721 at the tender age of twenty-four, when Cartouche was arrested by the police, condemned by the high court, and torn apart alive on the wheel. The chapbook Histoire de la vie et du procès du fameux Louis-Dominique Cartouche (“History of the Life and Trial of the Famous Louis-Dominique Cartouche”) appeared the year of his execution and became so popular that it was reprinted at least twenty-four times over the next century.

Trial and Life of the Famous Cartouche, and his many accomplices (Troyes: Baudot, 1772). Reproduced in Andries and Bollème, La Bibliothèque bleue, p. 466.

Eight additional Bibliothèque bleue titles about Cartouche followed, each printed in multiple editions. In both prose and play formats, these chapbooks extolled Cartouche’s clever criminal ruses, celebrated his skills as the leader of a vast criminal gang, and divulged the intimate details of his love affairs. The chapbooks portrayed the bandit sympathetically as a larger-than-life popular hero and a formidable opponent of established society.

Cartouche’s story begins with running away from his family at age ten to live with “Gypsies” (bohémiens) and learn their crafty ways. Taking up residence in Paris, he became a stealthy thief, expert pickpocket, and skilled in the art of travestissement or disguise, whether as a baker’s boy or a military officer. A born leader, Cartouche supposedly organized hundreds of decommissioned soldiers in Paris who had been reduced to penury and begging, as well as throngs of vagabonds, into an immense company of thieves. He was also renowned for a pair of pistols packed in his belt, and he did not hesitate to use them. Yet these chapbook accounts insisted that Cartouche did not have a taste for blood, and that he only killed in self-defense against guards and police agents who attacked him or as personal revenge against those who had betrayed him.

For the villains in Bibliothèque bleue stories about Cartouche were not the thieves and brigands, but the police and their spies. Until the sixteenth century, policing had been broadly defined juridically as a general responsibility of government, “the exercise of everything needed to look after the inhabitants and public well-being of a town” (Lebigre, p. 147). The Paris police only emerged as an official force in seventeenth-century France under the Sun King Louis XIV. By the end of the eighteenth century, it had grown into a city-wide organization and its agents were generally despised for the harassing the working poor and for the arbitrary arrest of “seditious” persons, who printed or distributed dissident political tracts (libelles) against the government or simply harbored such sentiments.

The role of the police and the courts in transforming Cartouche from a common thief and bandit into the infamous leader of a criminal band can hardly be overstated. In Arrest de la Cour de Parlement pamphlets, official court publications about criminal trials and executions, Cartouche and his accomplices were portrayed as hardened criminal recidivists. Belonging to Cartouche’s band became an official charge used to justify mass arrests, up to hundreds of people at a time, which helped to create the bandit’s image as the leader of a vast criminal organization.[2] Seven years after Cartouche’s execution in 1721, Lieutenant-General of Police Marc-Pierre d’Argenson led a massive crackdown on the pègre or the “lazy criminal class” of Paris. The High Court of Paris condemned nearly 750 persons for being members of Cartouche’s band, most tried in absentia, with the majority receiving a death sentence and dozens actually executed. The crackdown had the effect of galvanizing the poorer populations of Paris against the police.

In Bibliothèque bleue chapbooks, the bandit Cartouche was ennobled as a hero who relied upon courage, charisma, seduction, and ruse, rather than brute force. He was also held in high esteem for loyalty to his comrades. Admiration for Cartouche has continued to remain strong in collective French memory across the centuries. In Pierre Larousse’s Grande Dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle, the magnificent nineteenth-century multi-volume encyclopedia, Cartouche was lauded with positive attributes: “Talented, possessing an imperturbable sangfroid, courageous in all circumstances, demonstrating great facility with firearms, calmly committing murder without anger, and, thanks to his generous traits and gallantry towards ladies, escaping the feelings of horror invoked by other bandits of his sort.”[3] The admirable qualities of Cartouche constitute a long continuity in French popular culture as well. His exploits were rewritten and serialized in magazines and popular novels throughout the nineteenth century, and then reenacted in the movies and on broadcast television in the twentieth.

Over the “long nineteenth century,” from the end of the French Revolution of 1789 to the Great War of 1914, popular fascination with stories about rogues and criminals have origins in Bibliothèque bleue chapbooks and were subsequently incorporated, modified, and modernized in serialized French crime fiction. First and foremost, there is a continuity of popular fascination with the lives of criminals as social outcasts. Outlaws who evade, outsmart, and attack the police are celebrated as heroes. Among criminals, loyalty to one’s comrades is a virtue, although betrayal is common. To commit physical violence against those who have violated one’s sense of honor is accepted, and meting out vigilante justice as personal revenge is respected.

These kinds of sentiments were serialized and modernized over decades of print mass culture, producing a spectacular trio of popular heroes: shady detectives, elegant criminals, and dark avengers. Taken together, these character types are less opposed to each other, than they are closely related to and continually metamorphosing versions of one another. The shift from traditional to modern criminal heroes begins with Vidocq, the grand détective who went straight from prison to becoming the head of a specially appointed police security squad — and then got fired for irregular activities and growing suspicions that he was getting rich on the side.

NOTES

[1] La vie genereuse des marcelots, gueuz et boesmies, contenans leur façon de vivre, subtilitez et Gergon. Mis en lumière par Monsieur Pechon de Ruby, Gentil’homme (1596), reproduced in Roger Chartier, Figures de la gueuserie, Collection “Bibliothèque bleue” (Paris: Montalba, 1982).

[2] For example, Arrest de la Cour de Parlement, Rendu contre cent deux Accusez complices de Louis-Dominique Cartouche; portant condamnation de mort contre plusieurs; au fouët, fleur de Lys; galeres; bannissement, & plus ample informé contres aucuns. Signé Pinterel (Paris: Delatour et Simion, 1772); reproduced in Michael Ellenberger, Cartouche, un brigand sous la Régence: Documents historiques, mémoires et textes contemporaines, littérature et légende (Paris: Livres Anciens Chaptal/J. Espagnon & P. Le Bret, 2006).

[3] S.v. “Cartouche (Louis-Dominique),” in Grand Dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle, ed. Pierre Larousse, vol. 3 (1867). Author’s translation.

SOURCES

Lise Andries and Geneviève Bollème, eds., La Bibliothèque bleue: Littérature de colportage, Collection “Bouquins” (Paris: Robert Laffont, 2003).

Arlette Lebigre, “La genèse de la police moderne,” in Histoire et dictionnaire de la police du moyen âge à nos jours, eds. Michel Aubouin, Arnaud Teyssier, and Jean Tulard (Paris: Robert Laffont, 2005).

Hans-Jürgen Lüsebrink, Histoires curieuses et véritables de Cartouche et de Mandrin, Collection “Bibliothèque bleue” (Paris: Éditions Montalba, 1984).

Patrice Peveri, “De Cartouche à Poulaille: L’héroisation du bandit dans le Paris du VIIIe siècle,” in Être Parisien, ed. Claude Gauvard and Jean-Louis Robert (Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 2004).

Robin Walz © 2024

Leave a comment