Frontispiece portrait by Marie Gabrielle Coignet, in Mémoires de Vidocq, chef de la police de sûreté, jusqu’en 1827, vol. 1 (Paris: Tenon, 1828). Wikipedia Commons: Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

In both fact and fiction, Eugène-François Vidocq is often called the first modern detective. His life and exploits are recounted in the Mémoires (1828-1829), a sprawling four-volume collection of tales that aggrandize his adventures as a criminal, police informer, and the leader of a police security squad.

The first volume narrates Vidocq’s youthful escapades and life as a soldier, rogue, and con man. Dogged by misfortune, he was repeatedly arrested and incarcerated, would break out of prison, and inevitably was recaptured. The second volume recounts how Vidocq strove to escape this perpetual condition by becoming a police informer from within prison. His information proved so useful, that Chief Henry of the Second Division of the Paris Prefecture of Police decided his talents could be put to better use as the chef de la brigade de sûreté, the leader of a “security squad” that assisted police agents in identifying at-large criminals. The third and fourth volumes recount scores of cases in which Vidocq and his agents would infiltrate underworld criminal haunts, ferret out guilty parties, and turn them over to the police. Throughout the Mémoires, Vidocq is a virtuoso hero, a master of disguise and dissimulator who mingles easily with the criminal milieu and overpowers his adversaries. Vidocq’s security squad men obeyed him, and criminals feared him.

The longest and most extensively detailed case in the Mémoires concerns Adèle d’Escars, a prostitute and gang leader of thieves and burglars, whose story stretches across thirteen chapters in the fourth and final volume. At age fourteen, Adèle’s parents sold her to the Madame of a registered brothel. The alluring neophyte quickly learned the arts of seduction. In short order, she became an independent operator, well-networked across the criminal milieu. She was also protected by members of the police de mœurs, the “public morality police,” who supported her as their mistress.

Early in her career, Adèle served time in Saint-Lazare women’s prison for prostitution and dealing in stolen goods. Upon release, she reemerged more savvy and powerful than ever, adopting numerous aliases and directing the activities of multiple criminal gangs. Ultimately, however, Adèle was captured by two of Vidocq’s agents, Coco Lacour and Fanfan Lagrenouille, and placed into police custody. Charged and convicted of multiple crimes, once again she was incarcerated in Saint-Lazare prison and became the first woman in France sentenced to life imprisonment.

And none of it was true. The adventures of Adèle d’Escars had been published months previously that same year as a fictional novel by Louis-François L’Héritier, Vidocq’s ghostwriter, as Les Malheurs d’une libérée (“The Misfortunes of a Liberated Woman”) and inserted wholesale into the final volume of the Mémoires.[1]

The following series of blog posts explore Vidocq’s apocryphal life story, exaggerated exploits, and romanticized persona. Biographers openly acknowledge the fabricated dimensions his memoirs, yet by-in-large have accepted them as Vidcoq’s life story. They are not entirely mistaken to confound the legend with the man, as there are few independent sources about Vidcoq’s life from childhood through his stint as leader of the security squad, other than what is written in the Mémoires. And what rip-roaring tales they tell! Petty thief, picaroon, avenger, womanizer, master of disguise, redoubtable police agent — the allure is all too seductive.

Erroneous claims are often put forward concerning Vidocq’s accomplishments as a detective: organizer of a comprehensive file system on known criminals, inventor of fingerprinting, meticulous collector of evidence, and a logical genius who tracks down criminal culprits on the basis of such indications. In fact, such procedural and forensic developments in French criminology occurred toward the end of the nineteenth century (discussed in later blog entries).

As for Vidocq’s crime solving skills, Edgar Allan Poe’s fictional detective the Chevalier August Dupin, originator of the concept of “ratiocination,” commented:

The Parisian police, so much extolled for acumen, are cunning, but no more. There is no method in their proceedings, beyond the method of the moment. […] The results attained by them are not unfrequently surprising, but, for the most part, are brought about by simple diligence and activity. When these qualities are unavailing, their schemes fail. Vidocq, for example, was a good guesser, and a persevering man. But, without educated thought, he erred continually by the very intensity of his investigations.

“The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” 1841

Vidcoq’s adventures are thrillingly picaresque, yet they are a far cry from the methodical procedures followed by modern detectives, real or fictional.

Perhaps the greatest mischaracterization of Vidocq’s life and career is his supposed transformation from a criminal convict to a devoted police detective. The error stems from what logicians call the “genetic fallacy,” that is, selectively searching for antecedents that are attributed to later developments, rather than placing those specifics within the contextual framework of the times. When the Mémoires are situated among their cultural origins and in the historical moment, as well as over the course of Vidocq’s life, it becomes apparent that he was not a reformed criminal turned policeman, but the original shady detective.

As is well known, although not as readily emphasized, uncredited ghostwriters Émile Morice and Louis-François L’Héritier wrote Vidocq’s Mémoires. The title page announces that Vidocq had been “Chief of the Security Police until 1827,” although the contents of the first volume regale his life as a rogue and criminal, ending well before he became a police spy from within prison, let alone the head of an auxiliary security squad (and not an officer of the regular police). Aware that such a criminal emphasis might overshadow his career in this specially appointed position to assist the police, Vidcoq addressed the issue in the book’s preface (author’s translation):

Since January 1828, it has been my intention to wrap up these Memoirs, which I wanted to prepare myself for publication. Unfortunately, this February my right arm was broken in five different places, which abruptly altered those plans. Consequently, for the past six weeks I have been in a precarious condition, in the throes of horrible suffering. Under such cruel conditions, I wasn’t able to review the text or add the finishing touches. Meanwhile, the manuscript had already been sold to an editor who, in a hurry to publish it, suggested a copyeditor to me, a writer not known to me personally but well regarded in literary circles. As it turns out, he had recommended one of those hack writers whose tales of audacious exploits conceal his literary worthlessness, someone whose vocation is simply to make as much money as possible….

“Au lecteur,” Mémoires, vol. 1, 1828

Vidocq lamented that the unnamed ghostwriter, Morice, was a teinturier, someone who “tints” or “colors” a text, an embellisher more than an editor.

As a result, Vidocq confessed, the portrait written into this first volume more resembles that of a heartless, unscrupulous, remorseless, and unrepentant “Cartouche” than the transformed and honest man he would become. Vidocq wished the printed words would simply disappear. But, he bemoaned, at this point what was to be done? The volume was already in print and on display in bookstores. He neglected to inform his readers, however, that he had already received an advance of 20,000 francs for it from his publisher, Tenon. Whatever the shortcomings of this first volume, Vidocq reassured readers that a few truths about his life and character had still managed to come through. The rest of Mémoires, he pledged, would be completed by another and more competent writer.

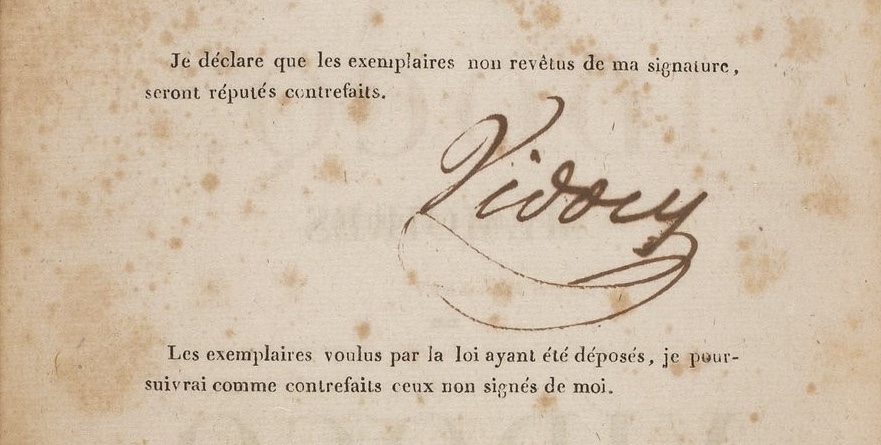

The promise was patently false, as the new ghostwriter, L’Héritier, served up dozens upon dozens of over-the-top exploits directed by Vidcoq, capped by the recycled story of Adèle d’Escars. To reassure readers about the authenticity of the subsequent volumes, Vidocq added a proclamation to the frontispiece of each title page: “I declare that issues of this book not bearing my signature should be considered counterfeits” (author’s translation):

From the frontispiece of Mémoires de Vidocq, vol. 2 (Paris: Tenon, 1828). Gallica: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Yet it remains unclear whether that declaration was meant to affirm the veracity of his memoirs, or if Vidocq simply wanted to distinguish between the commercially-authorized Tenon volumes of the Mémoires and other accounts of his life and exploits also in circulation.[2]

French biographer Eric Perrin has undertaken the painstaking work of cross-referencing several individuals arrested and convicted of crimes in the Mémoires with documentation in French national and regional archives. Still, the bravado Morice and L’Héritier infused into Vidocq’s memoirs, as well as cases they invented from whole cloth, supersede police and court records. Readers were enthralled by tales of Vidocq’s heroic exploits and insider descriptions of the criminal milieu, not by fact checking. In effect, Vidocq sold the Mémoires both ways, as true crime and confabulation. Vidocq claimed to provide readers with personally acquired insider information about the criminal milieu, while simultaneously issuing disclaimers that distanced himself from what was actually written on the page. Publisher Tenon and Vidocq banked on incredulous buyers suspending disbelief long enough to purchase copies of the Mémoires — a commercial strategy already employed by authors and publishers of crime chapbooks in France over the previous two centuries.

NOTES

[1] “17° L********* Les Malheurs d’une libérée. Paris, Tenon, 1829, in-12 de 154 pages. Ce roman a été plus tard inséré en entière dans les ‘Mémoires de Vidocq’.” S.v. “L’Héritier (Louis-François),” in J.-M. Quérard, La France littéraire ou dictionnaire biographique, vol. XI, Additions, Corrections (Paris: L’éditeur, 1857).

[2] Mémoires d’un forçat ou Vidocq dévoilé, 4 vols. (Paris: Langlois [vol. 1], Rapilly [vol. 2], Chez tous les marchands de nouveautés [vols. 3-4], 1828-1829); Histoire de Vidocq chef de la police de sûreté écrite d’après lui-même par M. Froment ex-chef de cabinet particulier du préfet, 2 vols. (Paris: Leroysey, 1829); Nouveau dictionnaire d’argot par un ex-chef de brigade sous M. Vidocq (Paris: Chez les marchands de nouveautés, 1829); Supplément aux Mémoires de Vidocq ou dernières révélations sans réticence par le rédacteur des 2e, 3e et 4e volumes des Mémoires [Louis-François L’Héritier], 2 vols. (Paris: Bouilland, 1830); Histoire de Vidocq chef de la brigade de sûreté depuis 1812 jusqu’en 1827, par G… (Paris: Chassaignon, 1830).

SOURCES

Clive Emsley, “From Ex-Con to Expert: The Police Detective in Nineteenth-Century France,” in Police Detectives in History, 1750-1950, ed. Clive Emsley and Haia Shpayer-Makove (London: Routledge, 2006).

Eric Perrin, Vidocq (Paris: Perrin, 1995).

Edgar Allan Poe, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841) in The Portable Poe, ed. Philip Van Doren Stern (New York: Penguin, 1977).

Eugène-François Vidocq, Les Mémoires de Vidocq, chef de la police de sûreté, jusqu’en 1827, aujourd’hui propriétaire et fabricant de papiers à Saint-Mandé, 4 vols. (Paris: Tenon, 1928-1829).

_____. Mémoires. Les Voleurs, Collection “Bouquins” (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1998).

Updated: November 8, 2024

Robin Walz © 2024

Leave a comment